Civitas Resources was fresh off of a merger deal with three Colorado E&Ps when questions about its drilling runway started to grow.

The deal among Denver-Julesburg (D-J) Basin producers Bonanza Creek Energy, Extraction Oil & Gas and Crestone Peak had yielded Civitas, the largest pure play Colorado producer. Chris Doyle had recently been brought in as president and CEO after an executive search.

Civitas had a strong position in the D-J Basin, Doyle told Hart Energy in an exclusive interview. These were high-quality assets with low breakeven costs that could generate strong volumes of free cash flow.

“It was a very successful business model for the first six, nine months of Civitas,” Doyle said.

“What we were really trying to do is: How do we take that business model that’s focused on shareholder returns, little growth, maximizing free cash flow, and how do we extend the duration of that business model?”

The company needed to find more inventory depth—ideally the same kind of high-quality, low-cost inventory already competing for capital in its D-J Basin drilling plans. But that was going to be a tall task to actually locate and buy in the D-J Basin.

At that point, the D-J was already significantly consolidated, Doyle said. The basin’s core was essentially already leased up by the likes of Chevron, Occidental, PDC Energy and Civitas itself.

And the basin consolidated even more when Chevron bought PDC for $6.3 billion last year.

“That really limited the opportunities for Civitas to continue to grow and extend our business model within the D-J,” Doyle said.

If Civitas couldn’t find the high-quality inventory it needed in Colorado, it needed to look somewhere else. So the Colorado pure play turned its attention south to Texas and New Mexico.

Doyle said Civitas knew it needed to enter a new basin—the Permian Basin, America’s top oil-producing region—with scale. Instead of dipping its toe into the pool, Civitas cannonballed its way into the Permian with nearly $7 billion in M&A in 2023.

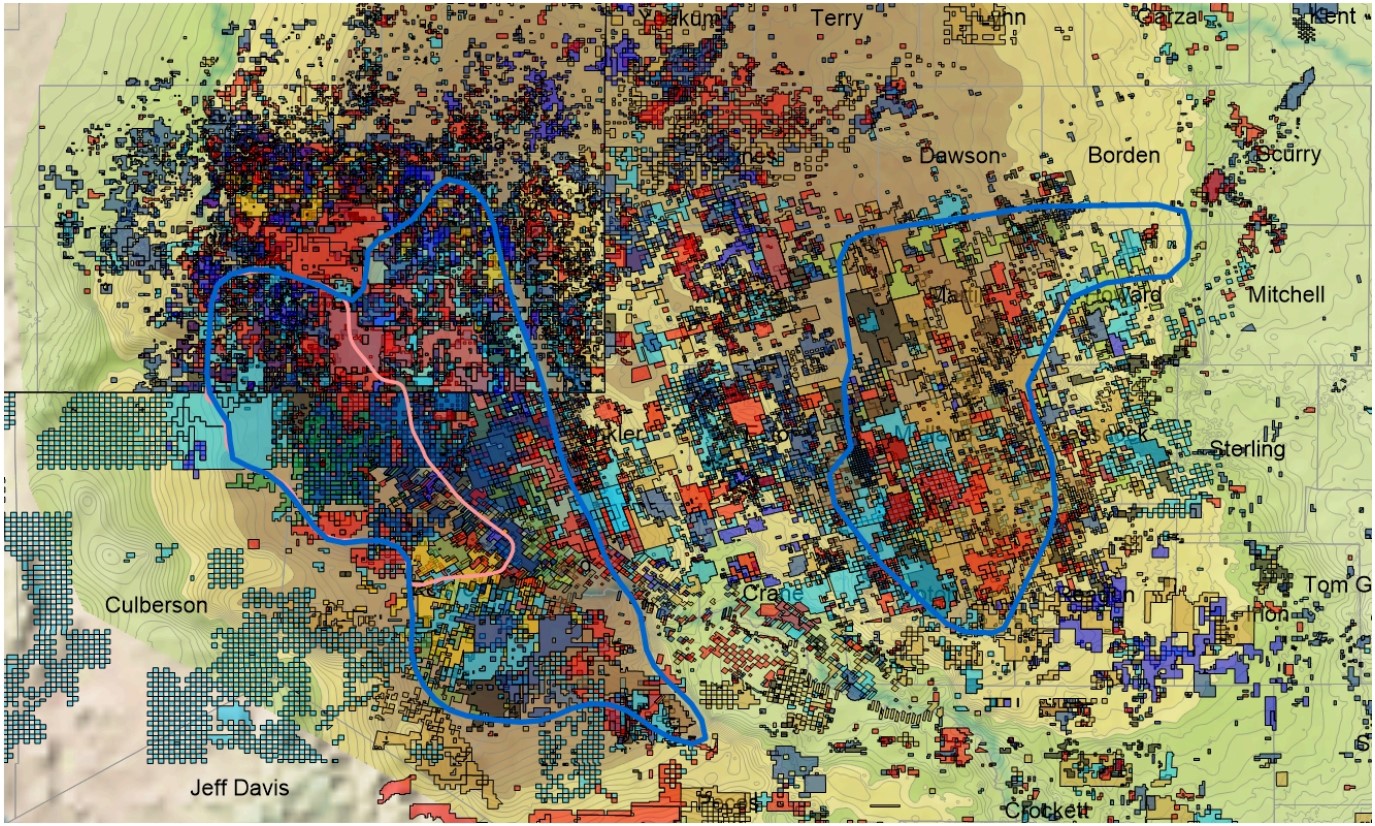

The first pair of deals, announced in June, included Delaware Basin assets from NGP-backed private operators Hibernia Energy III and Tap Rock Resources. Civitas agreed to pay $4.7 billion in a cash-and-stock transaction.

In October, Civitas entered the Midland Basin with a $2.1 billion acquisition of Vencer Energy. Vencer is backed by international energy trader Vitol.

Scale matters in the oil and gas business, Doyle said. Being bigger helps you negotiate more favorable services contracts to lower drilling and completion costs. You can be more efficient with your rigs and frac crews on a larger, more contiguous position. All of those help you lower the breakeven cost of your drilling inventory.

But scale also helps your balance sheet and trading liquidity. Larger companies generally trade at higher multiples than smaller players. And a strong, investment-grade balance sheet can help you access lower costs on bank debt—an important point with elevated interest rates.

Civitas has seen some of the benefits of scale: the company’s stock price was up nearly 25% year over year when the market closed on Dec. 22.

“I do think there is a recognition from industry that high-quality inventory and access to resource is more precious today than it was a year ago, or certainly a couple years ago,” Doyle said.

RELATED

Analysts: Civitas Digs Deeper into Permian with $2.1B Vencer Deal

Anatomy of a bonanza

E&Ps have spent years and billions of dollars innovating and trying to organically boost shale productivity. But a newer realization is settling across the shale patch: If you want the highest quality drilling inventory, you’ll probably have to buy it from someone else.

In our 2023 Shale Outlook, we highlighted efforts by Pioneer Natural Resources—one of the Permian Basin’s largest and most adept players—to overcome well productivity declines and a rising gas-to-oil ratio on its Midland Basin position.

These concerns weren’t exclusive to Pioneer. Exxon Mobil, Chevron and several other of the basin’s top operators were dropping their outlooks for Permian oil and gas volumes because of declining well production, services cost inflation and other headwinds.

E&Ps expressed optimism despite the challenges. Both Chevron and Exxon continued touting plans to push their respective Permian outputs up to at least 1 MMboe/d in the coming years.

Pioneer said it would go back to the drawing board and reshuffle its 2023 drilling portfolio to target wells that could potentially generate higher returns.

The industry believed it would be able to develop itself out of declining shale productivity, leaning on engineering innovation like the kind that ushered in a historic fracking boom more than a decade ago.

And beyond making development more efficient, there was still plenty of runway for the industry to continue drilling like it had been. In 2022, energy analytics firm Enverus Intelligence Research estimated there were 125,000 remaining undeveloped locations across North America that could break even below a $40/bbl WTI price.

A lot can change in a year.

Drilling and completion costs continued to rise. New well productivity in the Permian appears to have peaked and is declining moderately, and the basin’s gas-to-oil ratio continues to climb. The circumstances are even less rosy in more mature shale plays like the Bakken and the Eagle Ford.

Shale wells, by and large, aren’t getting all that much better: Average well productivity across U.S. shale appears to have peaked in 2021, according to data analyzed in reports by Bernstein, Enverus and Novi Labs.

The roughly 7,300 horizontal wells that came online during 2021 produced an average of 106,800 bbl/d of oil in their first six months of production, Novi Labs found. Meanwhile, the 3,000 horizontal wells that began production in 2023—and have been producing for at least six months—averaged 97,700 bbl/d, a decline of 4.2% each year.

Moreover, productivity declined despite average lateral lengths increasing from 9,200 ft in 2021 to 9,800 ft in 2023.

The conundrum is even more pronounced in Lea County, N.M., the heart of the Permian’s Delaware Basin and the only Permian county that produced more than 1 MMbbl/d in August 2023.

Well productivity in Lea County dropped by 16% over two years, despite a small increase in average lateral lengths.

Headwinds like rising drilling costs and declining productivity caused Enverus to recently reduce its previous estimates from 125,000 to around 75,000 remaining Tier 1 drilling locations, at a sub-$45/bbl WTI price, across North America.

At current activity levels, it represents just about six years of remaining top-tier drilling inventory across the continent.

And that top-tier inventory isn’t easy to find. The vast majority of the remaining Tier 1 drilling locations throughout all benches of the Midland and Delaware basins—approximately 80%—are held by a small number of public companies with a market cap of more than $30 billion, according to Wood Mackenzie research.

RELATED

Enverus: E&Ps Eye Deeper, Fringier Targets as Permian Basin Matures

Untapped potential

Civitas wasn’t alone in its U.S. shale aspirations. E&Ps big and small are spending billions to acquire undeveloped drilling inventory capable of generating returns even if oil prices slump below $40/bbl.

In a transaction that might be considered unthinkable a year or so ago, Exxon inked an agreement to acquire Pioneer Natural Resources in an eye-popping $60 billion deal, excluding the assumption of Pioneer’s net debt.

The megadeal adds Pioneer’s more than 850,000 net acres in the core of the Midland Basin to Exxon’s existing 570,000 net Permian acres. At closing, Exxon’s Permian production will more than double to 1.3 Mboe/d, based on 2023 volumes; Permian output will grow to 2 Mboe/d by 2027, up from Exxon’s previous goal of 1 Mboe/d the company laid out before inking the Pioneer deal.

In another large-scale Permian deal, Occidental agreed to scoop up private E&P CrownRock for $12 billion.

CrownRock holds one of the most coveted acreage positions among private Permian E&Ps. Occidental’s acquisition includes 94,000 net acres of stacked pay assets and a runway of 1,700 undeveloped drilling locations across the core of the Midland Basin.

Smaller players are also spending billions to add Permian runway: Permian Resources added runway in the Delaware and Midland basins through its $4.5 billion acquisition of Earthstone Energy.

Ovintiv acquired three EnCap Investments-backed portfolio companies for $4.275 billion to bolster its footprint in the Midland Basin. EnCap also sold Delaware Basin E&P Advance Energy Partners to Matador Resources for $1.6 billion last year.

Vital Energy’s desire to boost the oil weighting of its portfolio fueled nearly $2 billion in Permian M&A in 2023.

But public E&Ps are also looking for quality drilling runway outside of the Permian.

Chevron’s acquisition of Hess Corp. delivers the California supermajor some incremental onshore production from Hess’ large footprint in the Bakken Shale.

But Chevron’s $60 billion megadeal was mostly about getting into the action offshore Guyana, the world’s latest and most prolific oil discovery.

Those massive deals tighten an already tight market for quality M&A.

“Exxon and Chevron effectively took two of the best assets that were available for purchase off the board,” said Fernando Valle, senior oil and gas equity analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence.

“There isn’t another Pioneer out there,” he said. “There isn’t another Guyana out there for sale.”

RELATED

Which Assets Will Chevron Shop After $53B Hess Deal?

A new era?

The U.S. shale patch looks a lot different today than it did when horizontal drilling and fracking advances first unlocked tight oil and gas.

Droves of privately held independents were among the early pioneers in unconventional resource plays like the Eagle Ford, the Bakken and, more recently, the Permian.

As these basins matured over time, it’s become more difficult for the small players to compete with the scale and engineering prowess of the majors and super-independents.

As a result, there are fewer small independents out there. The most successful private players with attractive assets have been acquired and integrated into larger E&Ps.

Many of the less fortunate wildcatters restructured or liquidated their assets through bankruptcy during periods of low commodity prices like the 2014 global oil glut, the Saudi Arabia-Russia price war and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Emerging from the pandemic, the survivors of the great shale reckoning have worked to attract capital back into the sector by spending within their means and pushing oodles of cash back to shareholders.

Matthew Bernstein, senior shale analyst at Rystad Energy, colloquially refers to this period of capital discipline by the shale industry as “Shale 3.0”—a period in contrast to the early innovations of the fracking industry and the drill-at-any-cost boom the sector saw in the years that followed.

Bernstein said U.S. shale could be entering a fourth era defined by the largest players absorbing even larger swathes of tight oil inventory into their portfolios.

Experts expect the deluge of shale M&A to continue in 2024. With fewer attractive private E&Ps left to buy, Bernstein thinks the market could see more mergers between public players in the future.

“There’s certainly a tacit understanding moving forward for the next 10, 20, 30 years that the industry has a lifetime, both geological- and demand-wise,” Bernstein said. “And it’s really about being in the driver’s seat to be a competitive force in the long term.”

RELATED

Middle Innings: Shale E&Ps’ Slow Struggle to Woo Back Investors

Recommended Reading

Marketed: Anschutz Three-well Opportunity in Powder River Basin

2024-06-25 - Anschutz Exploration Corp. has retained EnergyNet for the sale of three wells in the Powder River Basin.

Marketed: Anschutz Exploration Niobrara Shale Opportunity

2024-05-29 - Anschutz Exploration Corp. has retained EnergyNet for the sale of a Niobrara Shale opportunity in Campbell County, Wyoming.

Marketed: Gulfport Appalachia Utica Oil Opportunity

2024-05-22 - Gulfport Appalachia LLC has retained EnergyNet for the sale of three EOG operated Utica wells in Noble County, Ohio.

Marketed: Anschutz Exploration Powder River Basin Opportunity

2024-06-20 - Anschutz Exploration Corp. has retained EnergyNet for the sale of a Powder River Basin in the Castle 3568-1324-1TH of Converse County, Wyoming.

Marketed: Legacy Income Five Well Package in New Mexico, Texas Counties

2024-05-21 - Legacy Income Fund I has retained EnergyNet for the sale of a five well package in Lea County, New Mexico and Loving County, Texas.