Shale pioneer and industry legend Aubrey McClendon unceremoniously stepped down from Chesapeake Energy in 2013 amid financial controversies.

Shortly thereafter, a little-known general manager from Anadarko Petroleum named Jason Pigott was hired as Chesapeake’s senior vice president for operations.

He was tasked with helping transform Chesapeake into, essentially, the anti-Aubrey corporation.

“I came in to lead a large portion of the company following a founder who had a very different strategy than what I learned at Anadarko, which was to be a lean organization with financial discipline, and not to chase acreage anymore,” Pigott said.

Fast forward 10 years, and Pigott is now preaching a blended strategy based on his years of experience–aggressive and acquisitive, but considered and fiscally conservative–to build the recently rebranded Vital Energy into a Permian Basin powerhouse.

“I did lots of divestitures at Chesapeake and not a lot of acquisitions, so that was a new muscle for me,” he said.

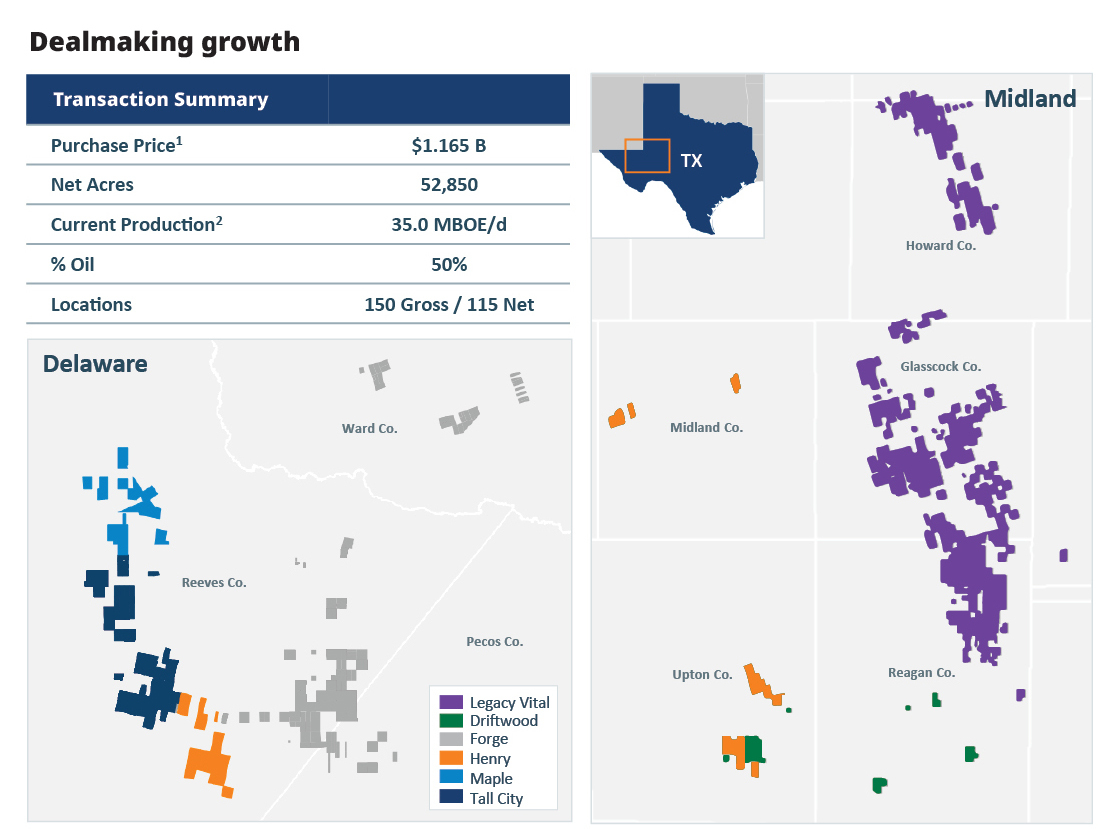

Since its transition from Laredo Petroleum to Vital at the beginning of the year, Vital has gone on a massive buying spree, scooping up five notable, private Permian producers for nearly $1.8 billion combined within a single calendar year.

The Permian M&A race for acreage is in full swing and Vital is doing much of its dealmaking under the radar with smaller, private players, while the headlines are dominated by Exxon Mobil paying nearly $60 billion for Pioneer Natural Resources.

This is a designed strategy for Vital, but Pigott acknowledges it’s also a matter of necessity, and is not about chasing acreage. Scale and inventory matter more than ever and are, well, vital to Vital’s future.

“I wiped out all the inventory when I came to the company [starting in 2019], and we've rebuilt it from scratch,” he said.

However, there’s caution at play too. Vital is seeking non-operated partners to share acquisition costs, leaning on equity to avoid deep debt, and maintaining a strong hedging program–a version of which kept then-Laredo from falling into bankruptcy during the 2020 oil crash and pandemic.

Marshall Hawkins/Hart Energy)

In February, Tulsa, Oklahoma-based Vital paid $214 million to acquire more oily Midland Basin acreage from Driftwood Energy. In June came the $540 million deal to enter the Delaware Basin by scooping up Forge Energy from EnCap Investments, but non-op partner Northern Oil & Gas covered 30% of the cost.

The biggest moves though came in September, acquiring Henry Resources, Tall City and Maple Energy for a combined 53,000 net acres within a matter of days of each other for a total of $1.165 billion, allowing the news to be released in a single announcement. Next year’s production is estimated at more than 112,000 boe/d, including 50% crude oil, up from about 33% just more than a year prior.

“We called it the Triple Lindy,” Pigott said, citing the classic Rodney Dangerfield film, “Back to School.”

“The deals took three completely different paths, but it looked like they were going to be within about a week of each other, so we just tried to thread the needle and get them all announced at one time,” Pigott said. “We knew it would be transformative for our company. We've more than doubled the size of our company. They all just came together really well, and added eight years of inventory.”

Learning to fly

The company rebranded from Laredo to Vital in January and then on Valentine’s Day–Vital has a flair for the dramatic–announced the Driftwood deal for 11,200 net acres.

But, as Pigott explained, there is a ripple effect in which consummating one deal begets another.

“When we did Driftwood, when you look on a [Midland Basin] map, Henry was all around it, and so we wanted to get to know the Henry team,” Pigott said, adding that he quickly became friendly with Henry Resources President David Bledsoe. “One of the things that has made us successful is just starting to build relationships.”

Well, it also turned out that the Southern Delaware portion of Henry’s acreage was virtually contiguous with the Forge acreage Vital had acquired.

The same applied to Maple Energy’s adjacent Southern Delaware position and to Tall City in the Delaware. Pigott had already met with the Maple team that was interested in selling, but the deal was too small as a Delaware entry point. However, it made sense after the Forge deal, Pigott said. Warburg Pincus-backed Tall City in the Southern Delaware was then won in an auction-based marketed process.

Henry was not initially up for sale at first, but that began to change in part with the failing health of founder and legendary wildcatter Jim Henry, who died in October at 89. The Henry portion of the deal was all equity for $517 million.

“Mr. Henry's health wasn't doing well and they were looking to not be an operator going forward,” Pigott said. “And so we just aligned. They wanted to take a heavy equity position in our company.”

This was all part of a planned strategy shift, he said.

“We pivoted this year to doing a series of smaller deals,” Pigott said. “You’re seeing all the big publics buying the big publics, and you're seeing bigger publics buy big privates, but there's no one out there that's working with these smaller private companies.

“I think we've been successful this year because we've purposely been pursuing that strategy of trying to create scale through a series of smaller acquisitions.”

It would be great to do nearly $2 billion in acquisitions again next year, he said, but it is easier said than done. There are still lots of opportunities, but fewer with each passing deal.

“We purposely went into the Delaware Basin with Forge because we think there's more white space on the map out there, more deal potential,” he said. “We see a lot longer runway in the Delaware.”

The key is striking the right balance, Pigott said, between not forcing deals and not wasting smart chances.

“We try to keep a conveyor belt of opportunities in front of us, and we're evaluating five or six things all the time,” Pigott said. “We've built this company to scale up, and so we never really want to slow down because the team is overwhelmed with the deal we've done. So we keep the pedal to the metal even after we've announced things.”

Won’t back down

That heavy-footed mentality is why analysts expect Vital to add at least $500 million in acreage deals in 2024, said Gabriele Sorbara, managing director of equity research at Siebert Williams Shank & Co.

“This [Laredo] was a name that was tough to get on people’s radars,” Sorbara said. “It’s getting bigger, and it’s getting noticed by more investors. They still have some work to do.”

Vital is beating Wall Street expectations on production and overall performance and its deals are accretive, Sorbara said, but Vital also must fight the perception of “shareholder overhang” from giving up a lot of equity to pull off the deals financially.

He said Vital is following a shrewd strategy of buying up so-called “Tier 2” assets in the Permian because it is virtually impossible to compete for the top available acreage.

“They’re not Tier 1, but they’re better than what Vital had, and that’s important. They’re continuing to improve,” Sorbara said. It is easy to point to other producers that are becoming less efficient while increasingly paying more for their wells, he added. Vital is instead on an upswing.

Vital’s legacy Glasscock County acreage in the Midland Basin was more mature and gassy. Vital needed the free cash flow and higher profits from more liquid acreage. So they bought into better Midland positons and then into the Delaware Basin.

“I think they’re more of a takeout candidate after the recent bolt-ons,” he said. But Vital may continue to want to grow and scale up for several more years to come, Sorbara added. After all, companies are paying high prices to acquire assets, but the premiums are not very high. Pre-pandemic, producers might buy other companies for premium 40% premiums on their stock prices. Now, sellers are fortunate to get a 15% premium.

“It’s just a different model now,” Sorbara said. “Scale is important. There are fewer investors out there. So how do we capture those fewer investors who are out there?”

Northern Oil & Gas CEO Nick O’Grady said his company’s aggressive expansion into the Permian as a non-operator has coincided nicely with Vital’s press to grow in the region.

He first connected with the Laredo team a few years ago as potential partners but nothing manifested despite the friendly dealings with Pigott and Vital CFO Bryan Lemmerman, who also followed from Chesapeake.

“The challenge of this is not only do you need to do the work and win the transaction, but you also have to agree with each other, right?” O’Grady said. “And engineers aren't known for agreeing with each other. So it took a couple go-arounds of looking at assets and maybe thinking differently.”

But when Forge came up for sale, both Vital and Northern were eyeing it independently. By the time they decided to potentially team up, they just needed to agree on a plan. O’Grady said his NOG team fell in line nicely with Vital’s plans for the acreage.

“Do I think that there's potential for similar deals? Absolutely,” O’Grady said, noting that such deals are more unique and the stars need to align.

With greater scale in the Delaware, Vital and NOG can keep services costs lower with more negotiating leverage and run a multi-rig program more efficiently, he said.

“You're dealing with a company that's hungry, looking to grow and really looking to improve the assets that they're purchasing,” he added. “We felt like Vital had a really viable plan from everything from operating costs to cutting drilling costs to being more precise. We knew we saw eye-to-eye looking at their development plan, which really focused on the highest quality prospects.”

Runnin’ down a dream

Pigott grew up outside of Corpus Christi in tiny Portland, Texas, and he was raised in the oil and gas sector by a father who worked for Amerada Hess.

Following in the industry, he took odd jobs painting handrails offshore and working as a roustabout before taking advantage of his math skills and going to Texas A&M for petroleum engineering.

Early production engineering gigs took him to oil and gas fields with Pennzoil and Union Pacific Resources. He joined Anadarko in 2001 and begin working his way up in management.

He even branched out into seminary school in the evenings. But it was during this time his family’s faith was tested.

A father of four, Pigott’s young daughter had strep throat and follow-up tests on a lump revealed stage-four neuroblastoma cancer.

“We go from strep throat to stage-four cancer with a 5-10% survival rate overnight,” Pigott said. “And this is where the Anadarko family just rallied behind us. I had to spend weeks in the hospital trying to choose whether you stay with your sick daughter or go to your three other kids at home. It was a terrible time in our life.”

Then came the waves of chemotherapy, stem-cell transplants and immunotherapy. And she is now 16 years old and cancer free, Pigott said with a smile.

“You have nothing but your faith to rely on when you're going through something like that,” he said. “And, today, I just realize and appreciate the work-life balance. Family first is one of our philosophies. If people [at Vital] are going through hard times, we try to rally around them as best we can.”

Pigott was recruited to Laredo in 2019 for his first CEO role to replace the retiring founder, Randy Foutch, but to also rally a struggling company. However, things would get worse in 2020 before they could get better.

And Laredo barely avoided bankruptcy. Pigott credited a conservative hedging policy that was already in place with saving the company. That set them up to grow as the industry rebounded in 2021 and 2022. And then it was time for a rebrand and the larger growth resurgence through dealmaking.

The new Vital name is about emphasizing the vital importance of American oil and gas to the world, he said, but also about ensuring the company plays a vital importance to the communities where it operates. Vital, after all, is the largest producer still headquartered in Tulsa.

“We ended up on this saying that we exist to energize human potential,” Pigott said. “So we want to have this mindset that we're impacting something greater in the world than just our wells in Midland. That also plays into the acquisition ramp that we've been doing. We will have a greater global impact the more that we produce. And being a small public company doesn't have too much of an impact on the world.”

Vital not only does a lot with charitable fundraising, but Vital also was the first publicly traded Permian producer to focus on verifying responsibly sourced gas while eliminating gas flaring as much as possible.

“To be important in the world and have an impact, we need to do it in a sustainable way,” Pigott said. “It was my mission to be the leader.”

So, what’s next? It’s clichéd to use baseball analogies for oil and gas, but the great American pastime is still an effective descriptor.

“We were working on small ball, which is hitting singles and doubles and doing smaller deals. But now we've doubled our equity value in the past,” he said. “I can now use [more] equity as part of a transaction, so we can do bigger deals.

“Because our success in small ball, we can hit triples and home runs in the future that we weren't able to before.”

Recommended Reading

E&P BW Energy Undergoes ‘Technical’ Ownership Restructuring

2024-05-08 - The restructuring will not involve any change to the ultimate control of BW Energy as the shares currently held by BW Group will be sold to BW Energy Holdings.

Wood Mackenzie Appoints Jason Liu as CEO

2024-05-07 - Liu replaces former CEO Mark Brinin, who is departing to pursue other opportunities, Wood Mackenzie said.

Hess Midstream Subsidiary Plans Private Offering of Senior Notes

2024-05-08 - The proposed issuance is not expected to have a meaningful impact on Hess Midstream’s leverage and credit profile, according to Fitch Ratings.

Exxon Appoints Maria Jelescu Dreyfus to Board

2024-05-08 - Dreyfus is CEO and founder of Ardinall Investment Management, a sustainable investment firm, and currently serves on the board of Cadiz Inc. and Canada-based pension fund CDPQ.

OFS Sector Loses Jobs, but Trade Org Says Growth Potential Remains

2024-05-08 - According to analysis by the Energy Workforce & Technology Council, the OFS job market may still have potential for growth despite a slight decrease in the sector in April.