Fracking innovation kicked off the U.S. shale boom. Too much drilling, too much debt and a global pandemic led to a shale bust, waves of bankruptcies and a flight of investment from the energy space.

Today, survivors of the great shale reckoning are working to attract capital back into the oil and gas sector—and trying to spend within their means to do so.

Gone are the days of chasing production growth or drilling at any cost. The 50 largest publicly traded oil and gas companies spent a collective $10.9 billion on exploration and $63.4 billion on development during 2022, according to data from EY’s latest U.S. oil and gas reserves, production and ESG benchmarking study.

But that’s nearly half of what the study group spent on exploration and development at the height of the shale boom in 2014, highlighting the industry’s shift toward capital discipline at the behest of investors, EY said.

“The industry is reshaping itself based on the near-death experience,” Dan Pickering, founder and chief investment officer at Houston-based Pickering Energy Partners, said in an interview with Hart Energy.

Today, the oil and gas industry is less aggressive on volume growth, more focused on returns and returning capital to shareholders and keeping debt leverage low, he said.

Instead of being laden with debt, E&Ps are operating leaner and choosing to tap into their own financial war chests to keep production relatively flat.

The U.S. shale sector today is a more mature, developed industry that needs a lot less cash than the drill-at-any-cost days of yesteryear. To that end, sources of capital that fueled the shale boom, such as private equity, are shrinking.

“But that also fits with a sector that doesn’t need as much external capital because they’ve got more of their own,” Pickering said.

Maintenance mode

Compared to the early days of the fracking boom, when investors and analysts chased production growth, the U.S. shale industry isn’t in a massive hurry to tap into its undrilled inventory.

In basins across the Lower 48, operators are jockeying for longevity, working to scoop up the quality undrilled inventory where it remains.

But overall, the amount of Tier 1 inventory remaining is dwindling as major oil plays, including the Permian Basin, the Eagle Ford and the Bakken, are leased up and developed.

“The commodities [prices] are better and the industry is better—the available asset to attack isn’t better, generally,” Pickering said. “We’ve pretty clearly defined the tier-one, tier-two and tier-three.”

Public E&Ps are having to do big deals in the hunt to deepen their inventory runway. And some of the biggest deals are getting inked in the prolific Permian Basin of West Texas and southeastern New Mexico, the Lower 48’s top oil-producing region.

Companies such as Permian Resources, Ovintiv, Civitas Resources, Callon Petroleum, Diamondback Energy and Matador Resources have been pouring billions of dollars into M&A to grow their respective Permian footprints.

Private operators and their investors have cashed in on the inventory scramble: Energy-focused private equity firm EnCap Investments monetized at least $7.5 billion in upstream investments from its portfolio in the first half of 2023 through several deals with public buyers.

EnCap sold three of its portfolio companies—Black Swan Oil and Gas, PetroLegacy Energy and Piedra Resources—to Ovintiv Inc. for $4.275 billion, bolstering the company’s footprint in the Midland Basin.

Matador Resources closed a $1.6 billion acquisition of EnCap portfolio company Advance Energy Partners Holdings LLC in April.

In mid-August, Earthstone Energy and Northern Oil & Gas teamed up to acquire EnCap-backed Novo Oil & Gas in a $1.5 billion deal. Just days later, Permian Resources announced plans to acquire Earthstone in a rarer public-public combination valued at $4.5 billion.

Experts largely expect the deluge of oil patch consolidation to continue. Large E&Ps are sitting on mountains of cash after raking in record profits in 2022, when commodity prices spiked amid a confluence of macroeconomic and geopolitical factors.

Where in the oil patch those deals get inked remains a fair question. With fewer opportunities to make acquisitions of undeveloped acreage in the center of the plays, E&Ps are having to consider smaller and fringier deals instead, said Neal Dingmann, managing director of energy research for Truist Securities.

“While there might be hundreds [of private E&Ps] out there between all the basins, there are very few that I could call core-of-the-core, or at least with any size out there,” Dingmann told Hart Energy.

The Permian is expected to drive the bulk of new U.S. crude oil production growth for the foreseeable future. But just like the Bakken and the Eagle Ford before it, the Permian is maturing and getting gassier as premium acreage is drilled up.

Even some of the most adept Permian developers see a line of sight to the basin’s peak production profile in the next decade.

“[By] the end of the decade… plus or minus a couple of years, you might see the Permian peak and start plateauing,” said Danny Wesson, executive vice president and COO at Diamondback Energy, during Hart Energy’s Super DUG conference in May. “The longer it takes us to get there, the longer it will plateau and run flat.”

“But the faster we get there, it will decline faster,” he said.

All of this helps set the stage for what has emerged as the go-to post-pandemic drilling strategy by a huge part of the E&P market: Don’t spend to drill through all that quality acreage today—because they’ll need it tomorrow.

Even when oil prices jumped back above $100/bbl last year, the U.S. oil and gas industry didn’t necessarily race to boost drilling and output; emerging out of the COVID-19 pandemic, total production grew by around 6% from around 11.27 MMbbl/d in 2021 to 11.91 MMbbl/d in 2022, according to Energy Information Administration data.

While overall exploration and development costs grew year over year from 2021 to 2022, exploration and development costs as a percentage of netback—revenues minus production costs—fell from 32% in 2021 to 28% in 2022, according to the EY study.

That’s because the largest oil and gas companies are spending less money on developing new production in order to send more cash back to shareholders.

“It’s less of the wild west—more manufacturing,” Pickering said. “And, the asset base itself is maturing.”

RELATED:

Diamondback COO: Permian Volumes to Peak Around 2030, M&A Competitive

Return of the returns

Oil and gas executives will often lament what they describe as a dearth of capital in the traditional energy space.

In reality, oil and gas companies are sitting on mountains of cash and, in many cases, generating more free cash flow (FCF) than ever before.

To win back the favor of the investment community, E&Ps are trying to return as much of that FCF as possible back to investors through dividends and share buybacks.

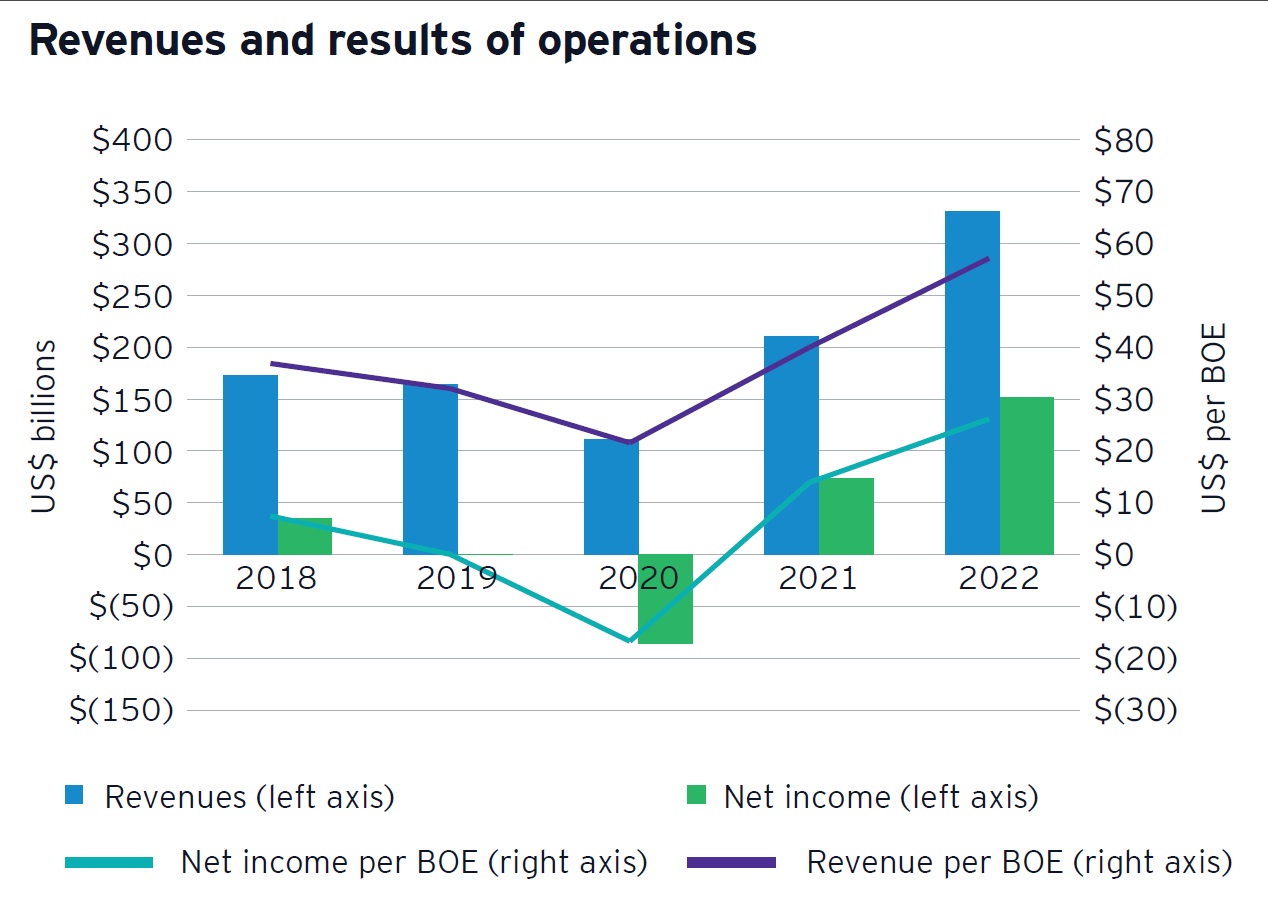

The top-50 industry players spent a collective $58.8 billion on dividend payments and share repurchases in 2022, a 210% jump from the $19 billion paid out the year prior, per the EY study.

Houston-based Coterra Energy Inc. managed to return 184% of its second-quarter FCF to shareholders, versus the company’s stated commitment to return 50% of FCF.

“The company's large cash balance afforded us the luxury to return capital in excess of our quarterly FCF and continue to buy our shares countercyclically at attractive prices,” Coterra CFO Shannon Young on the E&P’s second-quarter earnings call in August.

EY noted that part of the reason E&Ps have boosted shareholder returns in the past year is partly due to increased cash on hand realized from higher commodity prices in 2022.

But with commodity prices down significantly from levels seen last year, there’s a tension brewing between a company’s capital budget and its return-of-capital framework as the industry heads into 2024.

Coterra was able to generate significant FCF at recent strip prices to fuel share buybacks during the second quarter. But in a lower price environment, that bucket of excess FCF would be significantly smaller.

Coterra aims to keep a resilient base dividend payment as part of its shareholder return framework. But the company’s ability to buy back shares, issue special dividends and reduce debt using extra cash on hand would be more limited under lower commodity prices.

“I think that capital discipline in 2024 would win if it had to—if commodity prices went down,” Pickering said. “Later in this cycle, I think the capital budget will win.”

U.S. E&Ps aren’t rushing to drill new wells and boost production right now. Most of the top operators expect their production to remain relatively flat year over year.

But if commodity prices go up for a sustained period of time, investors could push E&Ps to drill more capital into the ground.

“As we have [a] duration of strong commodity prices, historically what you see is investors get excited,” Pickering said. “’Wow, look at the returns in this business,’ and they start pushing.”

“Right now they’re pushing for, ‘Give me the money back.’ I think this cycle ultimately finishes with investors saying, ‘Do more, do more, do more,’” he said.

Coasting, not accelerating

For the time being, and for the level of activity companies are currently targeting, the oil and gas industry has enough capital to sustain itself.

“I don’t think that we have too little capital,” said Pickering Energy Partners Managing Director Lex Hochner, who focuses on the firm’s private investment portfolio. “In fact, the industry needs less capital today for a few different reasons—one of which is our capital has become more efficient.”

Cash piles, while shrinking in a lower price environment, are still robust. The investment-grade debt market is plenty open, and the high-yield market is generally open.

Some signs of life have appeared in equity fundraising markets as private companies in the oil and gas space plan initial public offerings. Experts at Latham & Watkins told Hart Energy this summer that the number of energy IPOs could more than double by year-end.

Coming off of near-death experiences during the bankruptcy bust and the COVID-19 pandemic, the oil and gas industry has enough capital to coast through its current plans.

But as this industry knows well, times change—and they can change quickly.

The investment community is much less willing to help the oil and gas sector when times are tough and prices are low. When the industry is going through a trying period, there’s even less access to private equity capital. Institutional investors are much less willing to step in to support a teetering E&P with a stock offering.

But on the flip side, if the U.S. shale industry really wanted to about-face, put pedal to metal and accelerate output growth, access to capital might become a bigger issue for the sector.

“Right now, institutional investors don’t want to support it. Banks aren’t going to be aggressive lenders to the space,” Pickering said. “We’re still too close to the scars of the downturn to support a rapid acceleration.”

Recommended Reading

Keeping it Simple: Antero Stays on Profitable Course in 1Q

2024-04-26 - Bucking trend, Antero Resources posted a slight increase in natural gas production as other companies curtailed production.

NOV Announces $1B Repurchase Program, Ups Dividend

2024-04-26 - NOV expects to increase its quarterly cash dividend on its common stock by 50% to $0.075 per share from $0.05 per share.

Initiative Equity Partners Acquires Equity in Renewable Firm ArtIn Energy

2024-04-26 - Initiative Equity Partners is taking steps to accelerate deployment of renewable energy globally, including in North America.

Repsol to Drop Marcellus Rig in June

2024-04-26 - Spain’s Repsol plans to drop its Marcellus Shale rig in June and reduce capex in the play due to the current U.S. gas price environment, CEO Josu Jon Imaz told analysts during a quarterly webcast.

Ithaca Deal ‘Ticks All the Boxes,’ Eni’s CFO Says

2024-04-26 - Eni’s deal to acquire Ithaca Energy marks a “strategic move to significantly strengthen its presence” on the U.K. Continental Shelf and “ticks all of the boxes” for the Italian energy company.