Petrie Partners CEO Jon Hughes is the first to admit that he doesn’t run the biggest or flashiest investment bank.

Indeed, few are familiar with the firm outside of the oil and gas industry. The Petrie Partners team totals only about 20 employees, but when you’re surrounded by Goliaths, there are benefits to being the smaller, nimbler David.

It was Petrie Partners executives who advised Pioneer Natural Resources on its $65 billion acquisition by Exxon Mobil, and it was Petrie Partners advising Noble Energy on $7 billion of acquisitions that allowed the company to enter the Permian Basin.

The list goes on for the firm that, following the model of its predecessor Petrie Parkman & Co., has built a name and reputation for itself inside the relatively tight-knit oil and gas industry.

Leveraging geography has helped. By maintaining offices in oil and gas hubs like Houston, Texas, and Denver, Colorado, as opposed to the financial capital of New York City, executives were able to rub shoulders with titans of the hydrocarbon business and land some of their first major clients.

Tom Petrie, who transitioned to the firm’s chairman emeritus in May 2023, said this gave the firm a front row seat to watch U.S. shale development and the fracking revolution unfold.

Petrie remembers meeting Barnett Shale pioneer George Mitchell in the early 1970s, but he didn’t really follow Mitchell until shale development began to pick up. Little did Petrie know at the time that a firm tied to his name would advise on the largest U.S. shale transaction ever signed.

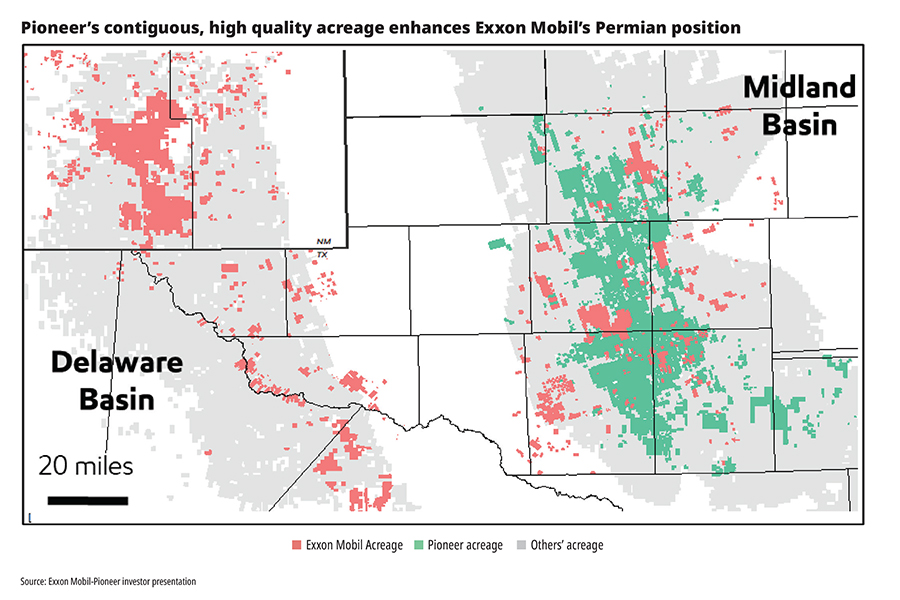

Exxon Mobil’s all-stock acquisition of Pioneer Natural Resources, valued at approximately $59.5 billion, or $253 per share, brings together two of the largest crude oil producers in the nation’s top oil-producing basin. Exxon Mobil will also acquire Pioneer’s outstanding debt.

The merger adds Pioneer’s over 850,000 net acres in the Midland Basin to Exxon’s portfolio of 570,000 net acres across the Permian. Combined, the company will have an estimated 16 Bboe of oil and gas resource in its Permian portfolio.

Petrie Partners, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and Bank of America Securities acted as financial advisers to Pioneer on the deal; Exxon Mobil was represented by Citi as lead financial adviser and Centerview Partners as financial adviser.

“We compete with the bulge bracket banks,” said Petrie Partners CFO Mike Bock. “This isn’t the first deal where we’ve been on the same side or the other side of Goldman, Credit Suisse, Morgan Stanley—all the big names.”

RELATED

As Pioneer Seals the Deal with Exxon, CEO Rich Dealy's Work Continues

Seat at the table

Whether its Exxon’s acquisition of Pioneer or the other transactions during an historically active M&A market, dealmaking is being driven by scarcity of quality drilling locations across the shale patch, Hughes said. And as geopolitical instability rocks Europe and the Middle East, the relative stability of operating in the U.S., or the Western Hemisphere more broadly, becomes even more attractive.

There has also been a recognition that the world is going to demand oil and gas for decades to come, Hughes said, and you can only do that if you have new locations to drill.

“High-quality drilling opportunities truly are limited because we’ve had a good decade of drilling A-plus inventory,” Hughes said. “There’s still some left, but it’s not as plentiful as it used to be.”

That’s particularly true in the Permian Basin, where the vast majority of the so-called “Tier 1” drilling locations are already held in the portfolios of a small number of public E&Ps. To get their hands on the best rock, operators, by and large, are having to go out and buy it from one, or several, of their competitors.

This scarcity-fueled M&A bonanza culminated in more than $100 billion in upstream transaction value across the Permian last year, according to a Wood Mackenzie analysis, though a huge chunk of that record total is represented by the Exxon-Pioneer tie-up. The previous record was $65 billion in 2019.

So, how does a small boutique firm land as an adviser on one of the largest oil and gas deals ever signed?

One major factor is firm partner Jim Rogers, who has maintained a long relationship with Pioneer. “As I like to say, he’s the new guy. He’s only been with us five years,” Hughes said.

The firm had an existing relationship with Exxon, so was able to act with trust and confidentiality with both sides of the table.

Andy Rapp, COO of Petrie Partners, said the firm has long acted as a sounding board for operators thinking about the direction of the energy industry or contemplating entering the A&D markets.

“It was a role that I think we were able to play effectively and confidentially for the senior management of Pioneer over the years,” Rapp said.

Being small can also be advantageous when trying to keep details about potential deals from finding their way outside the office walls. The Petrie team thinks confidentiality is more likely if fewer people are involved in the overall process.

“In the conflicts department at a bulge bracket firm, there are more people that have to know about clearing conflicts to sign up an engagement than we have employees,” Hughes said.

There were benefits of scale and status when the firm’s predecessor, Petrie Parkman, was acquired by Merrill Lynch in 2006. Then again after Merrill’s takeover by Bank of America during the financial crisis.

But there are also attractive features about not being a bank: no need for a balance sheet for oil and gas lending, no road shows with investors. Petrie Partners isn’t trying to commoditize the entire M&A advisory value chain like the big banks have tried to do, Hughes said.

“We work really hard on one deal and hopefully we get the next deal. Then that client mentions it to another client,” Bock said. “We don’t have to spend a lot of time pitching.”

“We have to win business on merit,” he said.

The executives also credit the longevity of the Petrie Partners team for some of the firm’s success in the market.

“This sounds arrogant but it’s true: We have really good people,” Hughes said. “We keep them, we train them. Andy, Mike and I have done that all our careers together.”

Then of course, there’s the benefit of the doubt that Petrie Partners receives by nature of Tom Petrie’s reputation within the energy industry, Rapp said. It helps when you’ve had a chairman of the board with over four decades of analyzing global commodity markets and brokering billions of dollars in transactions.

“We compete with the bulge bracket banks. This isn’t the first deal where we’ve been on the same side or the other side of Goldman, Credit Suisse, Morgan Stanley—all the big names.”

—Mike Bock, CFO, Petrie Partners

RELATED

Exxon Bringing Longer Laterals, New Tech to Pioneer Acreage

Petrie Parkman & Co.

Tom Petrie and Jim Parkman hadn’t even opened the doors to their new boutique investment firm, Petrie Parkman & Co., in 1989 when foundational oil and gas clients started to approach them.

Petrie and Parkman, both already veterans and influencers of the Wall Street financial world, met at the First Boston investment bank in New York when Parkman joined in 1982. But by the time that First Boston was being bought out by Credit Suisse in 1988, the two had decided to go their own way.

Still, leaving a major investment bank to start a single-industry boutique was a fairly novel idea in the late 1980s, Petrie said.

One of Petrie’s clients was Clark Johnson, CEO of Union Texas Petroleum; the two had worked closely together to get Union Texas Petroleum’s difficult IPO process across the finish line.

Petrie and Johnson were together at a dinner in Denver when Johnson made a proposal.

“When we went off to dinner, he held me back from some of his people and said, ‘I know in all likelihood you’re going to be thinking about what else you want to do after the Credit Suisse deal with First Boston closes,’” Petrie said. “‘And I just want you to know I want to be a founding client.’”

“I called Jim that night and said, ‘We’re off and running.’”

It wasn’t before long that Apache Corp. co-founder Raymond Plank approached the nascent investment bank seeking its services.

Plank had relocated Apache from Minneapolis, Minnesota, to Denver just a few years before Petrie Parkman launched. Petrie had known Plank since his time covering Apache as an oil analyst in the early 1970s, but Apache coming to Denver made it that much easier to check in with him.

Plank eventually came to Petrie Parkman with the goal of getting bigger.

“He was talking about how he’d founded the firm—he’d done it with drilling funds in the early years, in the ‘60s to early- to mid- ‘70s,” Petrie said. “But now, he really felt like he was ready to step up.”

The scale Plank was seeking came in the form of a large parcel in Texas and New Mexico that Amoco wanted to part with. The former Standard Oil Co. was well-known for making negotiations difficult, and the two sides were stuck on price.

Petrie Parkman came up with a production payment plan to bridge the wide gap between Amoco’s asking price and Apache’s own bid. The $550 million acquisition of MW Petroleum was completed in 1991, doubling Apache’s size.

“That reinforced what Clark Johnson had said to me, as well,” Petrie said. “If we are willing to work hard and really develop and deepen our network of contacts, we could have a base of business operating independently.”

Much of the firm’s early work focused on conventional assets. Unconventional development, horizontal drilling and the fracking revolution opened up new avenues.

One of the last things Petrie and Parkman did while at First Boston was finding a buyer for a client’s gassy shale properties in Appalachia.

After launching in Denver, Petrie Parkman started to assist clients with acquiring, trading and divesting properties in the Denver-Julesburg (D-J) Basin.

But one deal that really drove home the untapped potential of U.S. shale was the $421 million acquisition of Lyco Energy Corp. by Enerplus in 2005, Petrie said. The transaction included approximately 120,000 net acres of undeveloped land in Montana and North Dakota, and light oil production from the Bakken dolomite formation.

“It was the real evidence that the ability to develop the shale potential in oil was going to happen,” Petrie said.

The firm started to get in on the shale action itself, benefitting from the enormous amounts of new capital coming into the domestic oil and gas sector and the rapidly increasing value of land in several well-known basins.

Petrie recalls advising on a sale of Barnett Shale properties by privately-held Chief Holdings, one of the first large-scale unconventional asset divestitures in the market. Devon Energy picked up the Barnett assets for $2.2 billion in cash.

In 2006, Petrie and Parkman sold their firm to Merrill Lynch. Petrie became vice chairman of Merrill Lynch when the deal closed, while Parkman joined Houston-based Parkman Whaling. In 17 years, the firm had engaged in transactions totaling $84 billion.

There and back again

The acquisition by Merrill Lynch gave Petrie Parkman much greater scale, but longtime team members missed life as a boutique firm.

The big bulge bracket banks are able to work with larger balance sheets, but they are also encumbered by a lot more moving parts: one side of the coin is pushing the bank’s lending arm, another is pushing the hedging arm, or the asset management arm.

They’ve also got a lot more employees vetting and analyzing potential transactions—which can lend itself to leaks and lapses in confidentiality.

There’s a lot more turnover at the big banks compared to Petrie Parkman, as well. Several Petrie Parkman team members had worked together since the firm’s founding in 1989. Others joined the firm as it established itself as a player in the oil and gas M&A realm throughout the 1990s.

Hughes was one of Petrie Parkman’s first hires. He led the firm’s mergers and acquisitions business before eventually becoming head of investment banking and a member of the Petrie Parkman board.

Mike Bock joined Petrie Parkman in 1993; he brought new skills in finance and corporate balance sheets to the firm, Petrie said.

After graduating from Rice University, Rapp joined Petrie Parkman’s Houston office in 1999 to work on energy asset valuations, acquisitions and divestitures.

Petrie, Hughes, Bock and Rapp all joined Merrill Lynch through the acquisition in 2006, then moved to Bank of America when the giant bank swallowed up Merrill for $50 billion in 2008.

Not everyone was enamored by life under a big-name bank.

“After the financial crisis and becoming part of Bank of America, it was a challenge to integrate into an organization that big and to combine the Petrie, Merrill Lynch and BofA teams,” Rapp said. “But it also gave us a tremendous amount of ongoing autonomy—just the ability to keep doing the things that we felt like we did well and with the clients we knew and had great relationships with.”

By 2011, Hughes, Bock and Rapp were able to leave Bank of America Merrill Lynch to launch their own boutique advisory, Strategic Energy Advisors, focused entirely on energy transactions.

After back and forth with Bank of America Merrill Lynch on branding negotiations, Tom Petrie left to become the new firm’s non-executive chairman in 2012 and Strategic Energy Advisors changed its name to Petrie Partners.

Petrie had actually been planning to retire after leaving Bank of America, planning to budget more time toward writing his book, “Following Oil.” He found the idea of putting the band back together, so to speak, to be contagious.

But he did have a condition: Petrie wasn’t willing to be CEO of an investment banking firm again. So Hughes, with whom Petrie had worked together for 25 years at that point, agreed to become CEO to lead the next iteration of the firm.

“I thought very much that Jon had the skill sets and the vision to carry on,” Petrie said. “And as it turned out, that was the beginning of the entity that we talk about now as Petrie Partners.”

Deal deluge

Did the Exxon-Pioneer merger kick off a wave of scarcity-fueled upstream M&A activity?

Some analysts think so: When thought leaders make big moves, their competitors wonder if they need to make a big move, too. Others think the upstream industry was destined for more consolidation as top-quality drilling locations got developed and started to run dry.

Eye-popping and industry-shaking deals continued to get signed in fourth-quarter 2023 and first-quarter 2024:

• Chevron unveiled a $53 billion takeover of Hess Corp. in October 2023, picking up a piece of the world’s newest and hottest offshore oil discovery in Guyana;

• Back in the Permian, Occidental Petroleum plucked private E&P CrownRock off the drawing board for $12 billion;

• APA Corp. and subsidiary Apache acquired Callon Petroleum for $4.5 billion;

• Permian Resources added runway in the Delaware and Midland basins through a $4.5 billion acquisition of Earthstone Energy; and

• Ovintiv, Matador Resources, Civitas Resources and Vital Energy were among several acquirers of private equity-backed E&Ps in the Permian last year.

And despite significant volatility in natural gas prices, gas-focused M&A has also started to pick back up.

Chesapeake Energy and Southwestern Energy agreed to combine in a $7.4 billion merger, bringing together two of the top gas producers in Appalachia and Louisiana’s Haynesville Shale. Late last year, Tokyo Gas Co. subsidiary TG Natural Resources acquired Haynesville E&P Rockcliff Energy II for $2.7 billion.

All signs point toward an M&A deluge poised to continue for at least another six to 12 months, Hughes said. Petrie Partners aims to continue to be a sounding board, a trusted adviser and an advocate for the oil and gas industry as other companies evaluate the current M&A landscape.

“When you look back through history and when [the supermajors] get active, if you’re not paying attention or following it closely, you’re missing the boat,” Rapp said.

Recommended Reading

Analyst: Is Jerry Jones Making a Run to Take Comstock Private?

2024-09-20 - After buying more than 13.4 million Comstock shares in August, analysts wonder if Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones might split the tackles and run downhill toward a go-private buyout of the Haynesville Shale gas producer.

Quantum’s VanLoh: New ‘Wave’ of Private Equity Investment Unlikely

2024-10-10 - Private equity titan Wil VanLoh, founder of Quantum Capital Group, shares his perspective on the dearth of oil and gas exploration, family office and private equity funding limitations and where M&A is headed next.

Cibolo Energy Closes Fund Aimed at Upstream, Midstream Growth

2024-09-10 - Cibolo Energy Management LLC closed its second fund, Cibolo Energy Partners II LP, meant to boost middle market upstream and midstream companies’ growth with development capital.

Companies Take Advantage of ABSs to Finance Acquisitions

2024-10-17 - Some companies have taken advantage of asset-backed securitizations to monetize some of their cash flows and better position themselves for a sale.

No Rush: Post-M&A Frenzy, Divestiture Market to Pick Up by 2025

2024-10-07 - Lenders with a variety of capital structures are poised to fund the upcoming portfolio rationalization in the post-consolidation era, bankers and deal advisers said at Hart Energy’s Energy Capital Conference.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.