[Editor's note: This story is part two of the three-part "The Path Forward" special report. A version of this story appears in the May 2020 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

On March 9, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) decided to delay release of its monthly Short-Term Energy Outlook. It had to—the world its data depicted had gone to hell.

A sharply different forecast appeared two days later. The price of WTI, which in January was expected to average $64/bbl for the year, would average $43/bbl in 2020, the EIA said. Others would chime in later in the month. Barclays Plc predicted $28/bbl for WTI; Dutch bank ING saw $20/bbl for global benchmark Brent.

The collapse of OPEC+ on March 6 aimed a battering ram at crude oil markets. On March 9, it struck fiercely, tearing away 24.6% of WTI’s price. It struck again on March 16 (10.5%) and again on March 18 (24.4%).

The oil and gas industry has always embraced its roller coaster existence. Boom-and-bust is part of the lore, part of the drama and, for those who can outlast the bust to soar with the boom, part of the fun. But this downcycle is not akin to 2016, 2008, 1991 or 1973. It is fueled by fear of an invisible killer, stoked by a market conflict by foreign antagonists. This time is different, out of control, perhaps harsher, and many E&Ps will be unable to survive.

“I’ve seen a lot of stuff go on in the oil market in the past 35, 36 years that I’ve been following it, and I’ve seen a lot of things happen in the global economy, and I’ve never seen anything remotely like this, to the degree of uncertainty like this,” Craig Pirrong, professor of finance at the University of Houston’s Bauer College of Business, told Oil and Gas Investor. “That’s what really sets this episode apart from some of the grim episodes that we’ve experienced in the past.”

Volatile times

A truce between the Russians and Saudis might be conceivable, but negotiating with a pandemic is not an option. Until the spread of COVID-19 has been arrested, efforts to move toward recovery are essentially futile.

“The old adage, ‘low prices will cure low prices,’ is just not working,” Peter Fasullo, co-founder and principal at En*Vantage Inc., told Oil and Gas Investor. “That adage relies on two things: Once low prices have occurred, you get a bounce back in demand because prices stimulate the economy. People start consuming more because prices are low, and it throttles back supply. But the problem is, until the virus is controlled, and we have a handle on it, demand’s not going to bounce back. Gasoline may be selling at $1.50 at the pump; it doesn’t mean I can buy it and travel while current lockdowns are in place.”

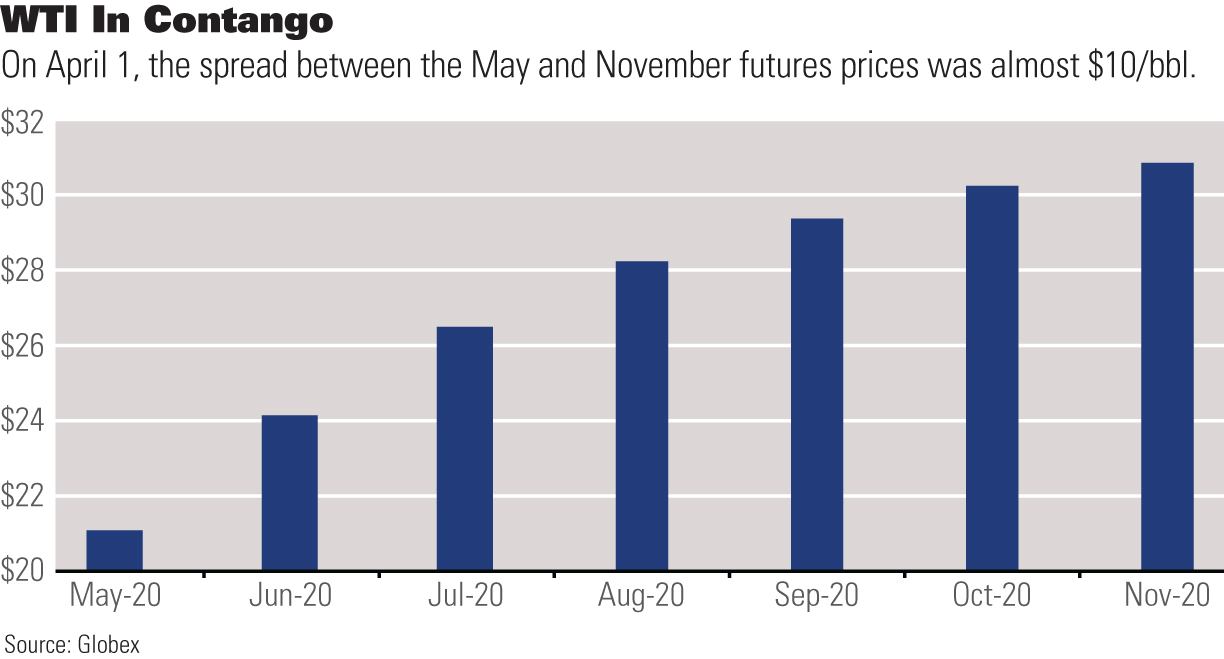

By late March, both WTI and Brent were in steep contango, meaning that the November price was well above the May front-month price. For WTI, the spread was about $10/bbl. That provides incentive for traders to buy up crude and pump it into storage, Pirrong said. Typically, that volume would spark an upward price trend, but the stranglehold that COVID-19 has placed on the economy stymies any significant movement. He expects commodities markets to convulse over the next three to six months.

“The market is also signaling that there is just a huge amount of volatility, and we could see, given this uncertainty, a dramatic change in either direction,” Pirrong said. “We could go back up into the $40s. The basic point is that there is so much uncertainty that we’re talking about a historically wide range around current prices and current futures prices.”

He does not really expect prices to sink to the teens, although he offers a 5% chance that they could. How about single digits? That’s unlikely, Pirrong said, but if the Saudis and the Russians continue to pump and flood the market, and the demand collapse driven by the virus persists simply because the virus persists, and that ocean of oil fills up storage then, in theory, crude prices could descend into the single digits. But he doesn’t consider it likely.

Driving the crisis is too much supply from U.S. unconventional fields, particularly the Permian Basin, and plunging global demand. En*Vantage expects U.S. producers to shed 1 MMbbl/d of their March average production of 13 million barrels per day (MMbbl/d) by the close of the second quarter. It won’t be enough because domestic demand will decrease by 4 MMbbl/d, En*Vantage said.

Global demand averaged about 100 MMbbl/d in 2019. The IEA and IHS Markit predicted demand will decline a staggering 20 MMbbl/d during the second quarter. Goldman Sachs forecast an 18.7 MMbbl/d plunge.

What’s the damage?

But prices don’t need to crater into the teens to elicit pain. In late March, the Dallas Federal Reserve determined that 35% of 107 E&Ps surveyed were conducting business in basins where the price had fallen below a level sufficient to cover operating expenses. The range in the Dallas Fed’s first-quarter energy survey stretched from $23/bbl in the Eagle Ford Shale to $36/bbl in nonshale basins. The average across the basins was $30/bbl.

On average, E&Ps said they needed the price to be $49/bbl to profitably drill a well. That average across the regions ranged from $46/bbl to $52/bbl, so if oil prices top out in the $40s, as Pirrong suggests might be the top of the range, it is an early signal that drilling could, at best, be limited for the foreseeable future.

“It’s a pretty bleak outlook,” Pirrong said. “Essentially, everybody in the industry is going to take a big hit, and that’s already reflected in stock prices, but the most vulnerable are the relatively leveraged E&P players, particularly in the U.S. shale. They just don’t have the balance sheets to survive.”

He anticipates a dramatic decline in U.S. drilling activity that will hit the oilfield service firms hard. High levels of unemployment can be expected as well, particularly among E&Ps.

The coming shakeout

Demand was entirely inelastic to price in March, Fasullo said, which put tremendous pressure on E&Ps to constrain supply. Making a very bad situation worse, Saudi Arabia, Russia and UAE are making plans to ramp up production. They, along with traders, are scrambling to secure ships to transport crude or store it as the global surplus grows. U.S. exports—which had been the solution for booming U.S. crude production—are currently, for the most part, greatly compromised. That’s because rapidly rising freight costs along with the global surplus have narrowed the price spread between Brent and WTI to under $4/bbl, strangling export economics. With U.S. oil demand contracting and exports sure to be threatened, storage becomes the only option to handle excess crude.

“As we put more crude in storage—which is limited—the challenge gets back to the E&P companies,” he said. “How fast can they throttle back? In a free market environment, throttling back production can be very uneven. Some companies are financially stronger than others, so some companies continue to produce. Some companies are more hedged than others, so they can continue while other companies can’t; some companies just have to produce to pay down debt.”

The great U.S. oil-producing machine has had massive forward momentum through 2019, and although it was expected to slow in 2020, it cannot stop quickly or easily even in this awful environment. Fasullo likened it to the time it takes to stop a supertanker. So, any additional crude on the market will exacerbate the low-price dilemma. The inevitable result is a slew of the oil patch’s weaker players forced into tough decisions about their future viability.

“What you’re going to see as soon as we get out of this: who are the winners, who are the losers?” Fasullo said. “Who’s going to get rationalized, whose properties may get bought. You may see the new world order of E&P companies after this is all over with.”

Read all of Oil and Gas Investor's "The Path Forward" special report:

Part 1: The E&P Survival Guide

Amid a pandemic and a disastrously timed OPEC+ supply war, executives, analysts and consultants advise hedging strategies, keeping a close watch on markets and, potentially, rebuilding business plans from the ground up.

Part 2: Full Reverse (story above)

Market forces are at competing odds, with a silent virus killing global demand for oil and foreign antagonists pushing more volumes into the supply pipeline. How does it end, and who wins—or just remains standing?

Part 3: OFS: Lower-for-Longer Scenario

As E&Ps jam the brakes on capex spend, the largest U.S. oilfield service providers respond in unison, cutting costs where they can and laying down equipment where they must.

Recommended Reading

Dividends Declared in the Week of Aug. 26

2024-08-30 - Here is a selection of dividends declared from select upstream and service and supply companies.

Talos Energy CEO Tim Duncan Steps Down; Mills to Take Helm

2024-08-30 - An analyst said Talos Energy President and CEO Tim Duncan was forced out over share price performance, although other factors may have played a role.

HNR Acquisition to Rebrand as EON Resources Inc.

2024-08-29 - HNR’s name change to EON Resources Inc. and a new ticker symbol, “EONR,” will take effect when trading commences on Sept. 18.

Hunting Wins Contracts for OOR Services to North Sea Operators

2024-08-29 - Hunting is securing contracts worth up to $60 million to deliver organic oil recovery technology to increase recoverable reserves for North Sea operators.

GreenFire Appoints Rob Klenner as President to Deliver Geothermal Solutions

2024-08-27 - As president of GreenFire Energy, Rob Klenner will be responsible for overseeing GreenFire’s geothermal energy projects.