[Editor's note: This story is part one of the three-part "The Path Forward" special report. A version of this story appears in the May 2020 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

In April, the streets of the world’s greatest cities emptied, offices and businesses shuttered, and humans huddled in their homes. The quiet grew, and the earth seemed to stand still.

It was the worst possible outcome for the oil and gas industry, which depends on all manner of movement—car and truck travel, airline flights, deliveries, logistics—for customers. By mid-April, as the coronavirus pandemic blazed through Europe and the U.S., the virus claimed 130,000 lives and restricted the movement of more than 300 million Americans. A supply war between Saudi Arabia and Russia only helped to further suppress oil prices.

Whether weeks or months of shelter-in-place orders—and lessened energy demand—lay ahead, the implications for the oil and gas industry are dire. The dog-eared E&P survival guide for the year ahead has once more been dusted off, but there’s no chapter for this. Generally, operators were responding rapidly through capex cuts, preparing for chaos and leaving all options on the table. And it may not be enough this time.

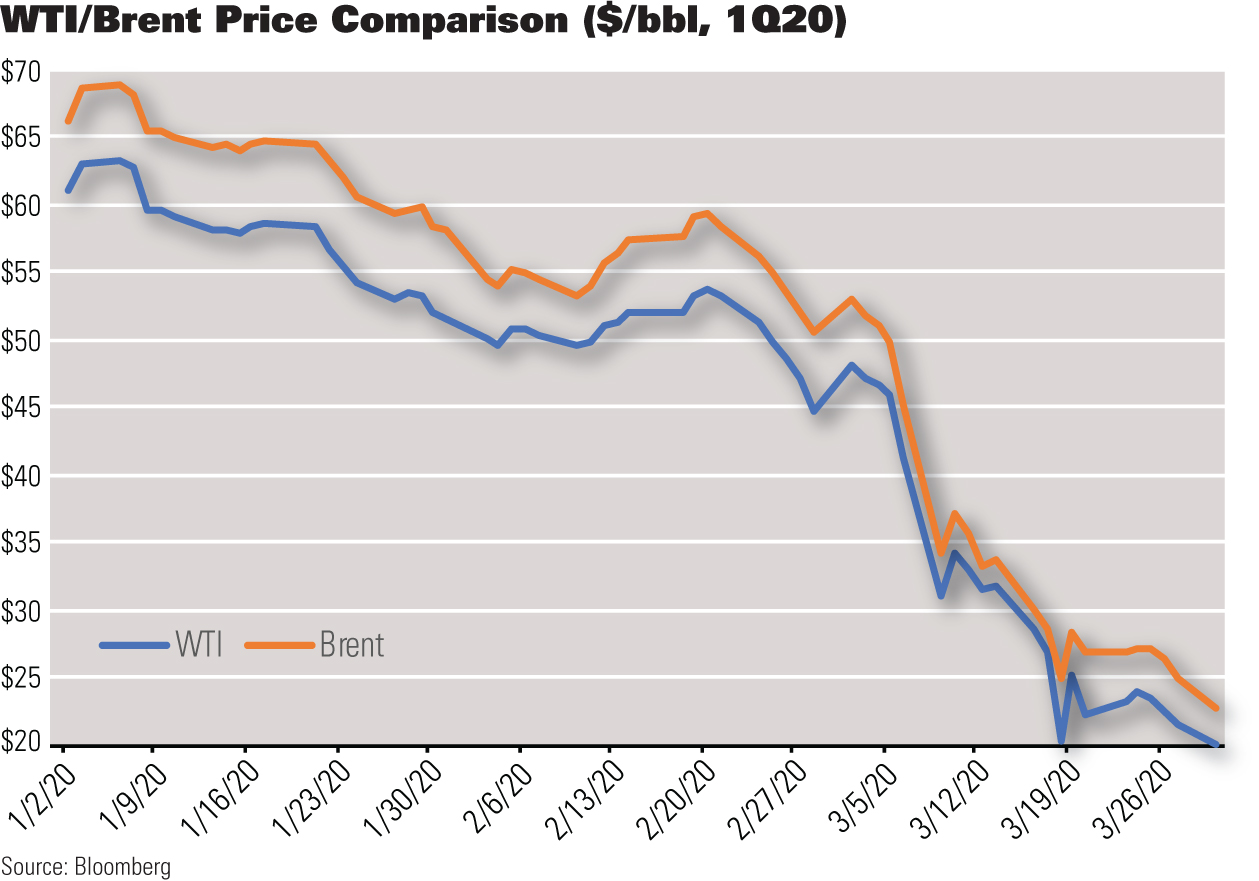

The swiftness of the March-April oil shock is unlike any that producers have faced before. In a matter of eight weeks, demand for oil was crushed, and prices skittered from $60/bbl to the low $20s.

The effects have been felt throughout all sectors of the economy, including hospitality, entertainment, travel and leisure. By early April, traffic through Transportation and Safety Administration checkpoints fell 94%—meaning 2 million fewer people traveled compared with the same time last year. Over New York, California and Texas, satellites tracking traffic showed declines of at least 50% each, according to Rystad Energy. In the U.S., jet fuel use is projected to fall by as much as 70% and gasoline by 50%, according to Regina Mayor, KPMG’s global and U.S. energy sector leader.

Estimates for crude oil demand are growing increasingly bearish, said Mayor. Models showed demand falling by “20 to 25 million barrels per day, globally,” Mayor said. “And those are now seeming to be pretty accurate. Just think about how our movements have changed for all of us.”

Industry leaders, consultants, analysts and executives say maneuvering through the crisis will require looking beyond the immediate aftermath of the price crash, which led to slashing capex and layoffs.

Harold Hamm, chairman of Continental Resources Inc., said the oil and gas industry has plenty of practice with business cycles and that the survival instincts of producers will kick in. “I think cutting back as much as you can, as quickly as you can and preserving cash and your liquidity is very important,” he said. “And that’s what everybody will strive to do.”

Jeffrey Currie, an analyst at Goldman Sachs, wrote on March 30 that carbon-based industries such as oil production have historically served as the cornerstone of social interactions and globalization—and those must be shut down to defend against the virus.

“Oil has been disproportionately hit, likely more than 2x economic activity, with demand this week down an estimated 26 million barrels per day or [about] 25%,” Currie said.

Unlike other industries, oil and gas producers are fighting a two-front war: demand destruction by the pandemic and the OPEC+ price war that has already unleashed a glut of oil on an already supersaturated market.

An angry Hamm said he is working with U.S. Sen. Jim Inhofe, R-OK, to place sanctions on the two countries for potential excessive dumping of oil into global markets. It’s unclear whether a late-breaking agreement by OPEC+ to curtail production by nearly 10 MMbbl/d would alter Inhofe’s response.

“The ironic thing is the U.S. [military] is over there [the Middle East] actually … protecting their physical and national security interests at the time that they choose to do this and undermine ours,” Hamm said.

Hamm said a countervailing duty of as much as $25/bbl could be imposed, though the American Petroleum Institute is generally opposed to tariffs. Hamm said that Saudi Arabia and Russia miscalculated “the ire of everyone here in this country” as they drove supplies up and prices down.

“The Saudis … didn’t just ramp up their production to two and a half million barrels,” he said. “Actually, what they did was ramp up production and empty their tanks. So, they wanted double the impact on the market, and they’ve done that.”

Even without the added pressures from the price war, Rystad forecast on April 1 that global demand in 2020 would contract by 6.4% because of the pandemic—about 2.5 billion barrels fewer than in 2019.

E&P executives, analysts and advisers urged upstream oil and gas producers to adjust to the reality that the pain will be long term. Even a truce between the oil price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia “is a little bit akin to spitting in the wind,” said Ian Nieboer, managing director at RS Energy Group.

Nieboer said what’s to come for upstream oil and gas producers amounts to a “buffet of bad choices.”

Taking a toll

Since the beginning of humanity, germs have taken their toll. But “we have developed resisting power; to no germs do we succumb without a struggle,” H.G. Wells wrote in “The War of the Worlds.”

The same could be said of oil companies and down cycles. But after years of cutting costs, bankruptcies, price wars and Wall Street apathy, the mood among executives was grim in April. Some suggested M&A would simply speed up consolidation already underway. Others said they would monitor and react to the new developments day by day. And a few advocated a hard reset.

But Hamm wonders how long the economy can remain at a standstill.

“Whether it lasts 60, 90 days, whatever, before people go back to work, our economy, in my opinion, cannot afford to be shut down like it is today for over three months,” he said. “I just don’t see that being possible.”

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) on April 2 reported that the unemployment rate is expected to exceed 10% in the second quarter, reflecting 9.9 million unemployment claims reported from March 27 through April 2. The CBO “expected the effects of job losses and business closures to be felt for some time” with an unemployment rate of 9% by the end of 2021.

Mayor said her clients are overly pessimistic as storage fills and demand dwindles.

“The mood is very grim, and it’s grim across the board: upstream, downstream, independent, integrated,” she said. “I don’t see really anyone seeing this as an opportunity.”

So far, Mayor said, companies have been enacting short-term measures, including slashing capital spending and operating expenses and shoring up liquidity and access to debt.

“Some are better able to do that than others,” she said. “I think some have started to take on workforce reduction and others have sacrificed the almighty dividend.”

Producers instinctively plowed down previous spending plans, with Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co. anticipating an overall 50% cut in oil and gas capex. Among companies covered by Cowen analysts, 2020 capex was down by 20%, or about $9 billion.

After oil prices tumbled in March, The Woodlands, Texas-based Earthstone Energy Inc. responded with a two-thirds cut to capex to a midpoint of $55 million, down from $165 million. The company plans to drop its single rig in the second quarter and limit completions to three wells already in progress. Assuming $30/bbl WTI and existing service costs, the company said it expected to generate free cash flow.

Robert Anderson, the newly appointed CEO of Earthstone, said survival—regardless of how low WTI sinks or rises—comes down to managing debt, revolver use and a hedging strategy.

Earthstone’s hedging strategy utilizes swaps, hedging 18 to 24 months out at 65% or more of its production forecast. The company doesn’t use debt to acquire acreage.

“With low debt, strong operations and low G&A, for a small-cap producer, we are well situated to handle prices even into the low teens,” Anderson said. “We averaged about $13.50 per boe for all-in cash costs in 2019. This includes all cash costs to run our business. Without being forced into shutting wells in due to constraints we can’t control, we would expect to continue to produce. We will have 11 wells drilled and waiting on completions so, when prices improve, we can quickly resume capital spending and bring on new production.”

Oklahoma-headquartered WPX Energy Inc. cut $400 million, or about 25%, of its capital budget. At the time, the company planned to maintain oil production of about 150,000 barrels per day for the rest of the year.

“We’re seeing capex budgets being revised down by 30% from original guidance,” Linda Htein, senior research manager for Wood Mackenzie, said on a webcast in late March. Among these are shale player EOG Resources Inc., which cut its capex by 30% and shifted from guidance of double-digit production growth to roughly flat compared to last year. Others, such as Permian Basin operator Pioneer Natural Resources Co. cut its budget by 45% and its rig count by half.

“That sounds dramatic, but we’ve actually seen more dramatic cuts than this,” Htein said. “Apache, for example, had eight rigs running in the Permian, and they have plans to drop all eight of them.”

Mayor warned that the world that emerges from the coronavirus may be radically different. One senior executive told Mayor in late March that oil prices may eventually sink into the single digits before rallying.

Longer term, E&Ps will need to fundamentally reevaluate their entire operating structure, she said. “We’re recommending folks start rethinking from the ground up, reprioritizing the entire portfolio,” including which basins and projects are viable and whether regional offices still make sense, she said.

“I think they have to start literally from a clean sheet of paper because just trimming off the edges and even cutting into the muscle isn’t going to be enough to deal with the fact that we went from a $60 price environment to the low $20s in the span of eight weeks,” Mayor said.

Companies in the best condition to survive should reshape their operating structure, cost basis, their portfolio strategy and generally rebuild from the ground up.

“They don’t have the luxury of doing that right now, but this is going to be with us for the next 12 to 18 months at the earliest before we even start to begin to come back.”

Cuts, vol. 2

A few companies, including Diamondback Energy Inc. and Occidental Petroleum Corp., announced a second round of operational changes—in the same month. More were expected to follow.

Others, such as WPX and EOG Resources, preached patience and flexibility.

Kenneth Boedeker, EOG Resources’ senior vice president of exploration and production, told investors at the virtual Scotia Howard Weil Energy Conference that, if warranted, the operator can flex down its planned 2020 capital spending program below the 30% cut announced in March. The company already dropped its capex plans to between $4.3 billion and $4.7 billion and added that the revised budget still offered strong returns at $30 oil. However, with the price per barrel sinking further, the company may adjust the plan again.

“We have a midpoint of $4.5 billion at this point, and we have a significant amount of flexibility in our plan to get there,” said Boedeker. “In terms of plan C, we continue to have a significant amount of flexibility in our plan and in our operations both in rig count and in frac crews. If these prices persist, we have the flexibility to go ahead and flex our capital plan even further down. We’re watching prices day-to-day, but we’re not knee-jerk reacting to any change in price.”

The initial funding cut spared most development programs in the Permian and Eagle Ford. EOG also said it would move forward with other infrastructure projects that would help the company on the other side of the price slump, including possible gas gathering and water projects. However, all projects will be reviewed if further cuts are needed.

“If we continue to cut then what we’ll see is we may reduce some of those plans in other areas as well as cut in the Eagle Ford and the Permian,” said Boedeker. “Our sacred cow is returns. We’re going to go wherever we can generate returns at those oil prices.”

At year-end 2019, EOG had over $2 billion in cash on the balance sheet and around $1 billion in debt maturities due in 2020.

“We have a significant amount of flexibility both operationally and financially to meet whatever pricing environment we see in the future,” Boedeker added. “We’ve learned from past downturns how to manage through these and how to structure our contracts to give us the maximum flexibility to react to substantial price reductions like we’ve seen over the past few weeks.”

Anderson said Earthstone can produce oil into the low teens and still be confident in covering its costs.

“A glut of oil and storage filling up sounds like it is happening in real time. This virus has created a drop in demand that we have never seen before,” he said. “We are taking this one day at a time and, as a small producer, we don’t have access to meaningful storage. If we get to the situation of having to reduce production or flat out shut-in wells, we will go through an orderly process to do so.”

Borrowed time

Triple Crown Resources LLC CEO Ryan Keys said he expects to see the needs of company balance sheets driving M&A. He also suspects companies will suffer after borrowing base redeterminations, which have the potential to complicate E&Ps’ debt positions.

“By the time we get to fall redetermination season, there will be a lot of assets from distressed and Chapter 11 companies being auctioned off,” Keys said. “Some banks with big enough portfolios have decided they’re going the ‘smashco’ route after they end up owning the assets.”

Other E&Ps may survive one or two redetermination seasons, “but they’re basically slowly melting ice cubes with no chance to recover. Those guys need to merge with someone in all-equity deals.”

Bankruptcies are already brewing with Denver-based Whiting Petroleum Corp. declaring bankruptcy April 1. Reuters reported the same day that Callon Petroleum Co. hired advisers to restructure its more than $3 billion in debt. Callon declined to comment on the report.

The Baker Hughes Rig Count continued to a precipitous drop, with 64 rigs falling in the U.S. between March 27 and April 3.

Keys said much of the debt owed by companies will trade at distressed or junk levels that is still viable by proved developed producing assets at strip pricing. That will open the door to capital willing to risk a Chapter 11 bankruptcy to own good assets—or ride an oil recovery to high dividends.

“I would love to have a lot of capital to deploy right now,” he said.

Beyond cutting, the options get more painful or more profound. Companies are already grappling with whether to shut in producing wells, gauging a Texas proposal for oil quotas, and how much more to cut and how deeply.

Longer term, laying down rigs might be an option but isn’t viable or realistic.

“Cutting to zero capex certainly will allow you to generate free cash flow, but the loss in EBITDA and borrowing base availability due to falling volumes becomes problematic after a period of time,” said Robert Turnham, president and COO of Goodrich Petroleum Corp.

Coping with decline rates also becomes problematic.

However, there are some “interesting dynamics” on the gas side in the Lower 48—less associated gas from oil plays as producers slow down activity, according to Wood Mackenzie.

That could bode well for Goodrich, an independent with assets in the Haynesville, Tuscaloosa Marine and Eagle Ford shales. Nearly all of its production is natural gas.

“Lower volumes in Permian and elsewhere obviously take associated gas out of the supply mix, which will benefit natural gas prices,” Turnham said. “We likely won’t see the prompt months move to acceptable prices

until COVID-19 is behind us, global growth in GDP resumes and LNG overhang is eliminated, but you are already seeing higher natural gas prices in the back of the curve reflecting this dynamic.”

Higher gas prices could incentivize new drilling in dry gas plays, particularly in the northeast region and the Haynesville, Htein said, helping to balance the gas market in 2021.

In all, the U.S. shale industry could do more to remain competitive in uncertain times. Reducing fixed costs and continued consolidation to “reduce redundant costs” across companies come to mind for Anderson.

“As we have seen over the past couple of years, there are too many companies with too much G&A [general and administrative expenses],” Anderson said. “We need to create scale to be competitive and reduce the fixed costs across the industry and lower the costs of operations. Scale does drive down the overall cost of the business, and we plan to be a consolidator and continue our cost-efficient operations.”

Generating competitive free-cash-flow yield to pay down debt and right-size balance sheets is essential, according to Turnham. Then, “companies will be paid again for growth and inventory.”

“The pandemic will be behind us soon and combined with low commodity prices demand will snap back at a time when supply growth has stopped,” Turnham said.

In the meantime, the industry must work through the supply overhang until prices recover. It’ll be “tough sledding for a while but the decisive, fundamental moves that we are all making will right the ship,” he said, recalling advice from a prominent Wall Street executive to “look over the valley to the other side; there are better days ahead.”

SIDEBAR:

Shut Out

Permian Basin operator Triple Crown Resources LLC is keeping watch, ready to weather the pandemic storm and the oil price war, CEO Ryan Keys said. But the way forward for most E&Ps will be treacherous.

Several analysts predicted that operators may shut in wells as a pandemic drastically undercuts demand for oil.

“My team is prepared and knows exactly what to do and at what prices or physical constraints, down to the individual well,” Keys said. “I don’t think many E&Ps are doing that, so I think the inevitable production curtailment—whether by force majeure or by economics—is going to be a disaster for many operators.”

Several analysts predicted varying degrees of shut-in production as prices fall and crude oil storage becomes scarce. Rystad Energy predicted that a third of U.S. storage capacity will be filled in April.

“Shut-ins are coming, and they are likely to be big,” Enverus said in an April 8 report.

In Texas, Pioneer Natural Resources Co. and Parsley Energy Inc. petitioned the Texas Railroad Commission (RRC) to impose regulations curtailing oil production by May. A hearing on the matter was set for mid-April. Any production curtailments would be significant as Texas is the nation’s largest producing state, accounting for 41% of U.S. oil production in 2019 and 25% of natural gas.

So-called proration, first implemented on a voluntary basis in Texas in 1927, would limit state oil production based on market demand that causes physical waste. Pioneer and Parsley argue in a motion for a hearing that the RRC should determine whether oil is being wasted or is in reasonably imminent danger of being wasted. The companies cited a lack of storage and low oil prices to suggest as much as 7 million barrels per day of oil production could be shut-in or not produced.

For shale producers, decisions to shut in production will likely involve a complex equation including price, long-term well performance, lease commitments and regional price and demand sensitivities, Goldman Sachs analysts said in an April 3 report.

Analysts at Morgan Stanley and Wood Mackenzie have said they have already seen signs of wells being closed.

“We’ve already seen confirmed cases of that occurring in the Eagle Ford [Shale] that some of my clients have said to us and is most likely happening to some small degree in other regions,” John Coleman, principal analyst at Wood Mackenzie, said during an April 2 webcast. “I think it’s not going to be as simple as high-cost regions are going to be the ones that shut in. It’s going to happen across the board, and it’s going to be on an operator specific basis, based on how much pain they can sustain.”

Regina Mayor, KPMG’s global and U.S. energy sector leader, said her clients are looking more toward deferring wells or slowing production without harming production curves.

“Shutting in production is a tool of last resort,” she said. “That’s not to say that you won’t see some [operators] do it. I just don’t see that as being a big lever that ends up coming into play.”

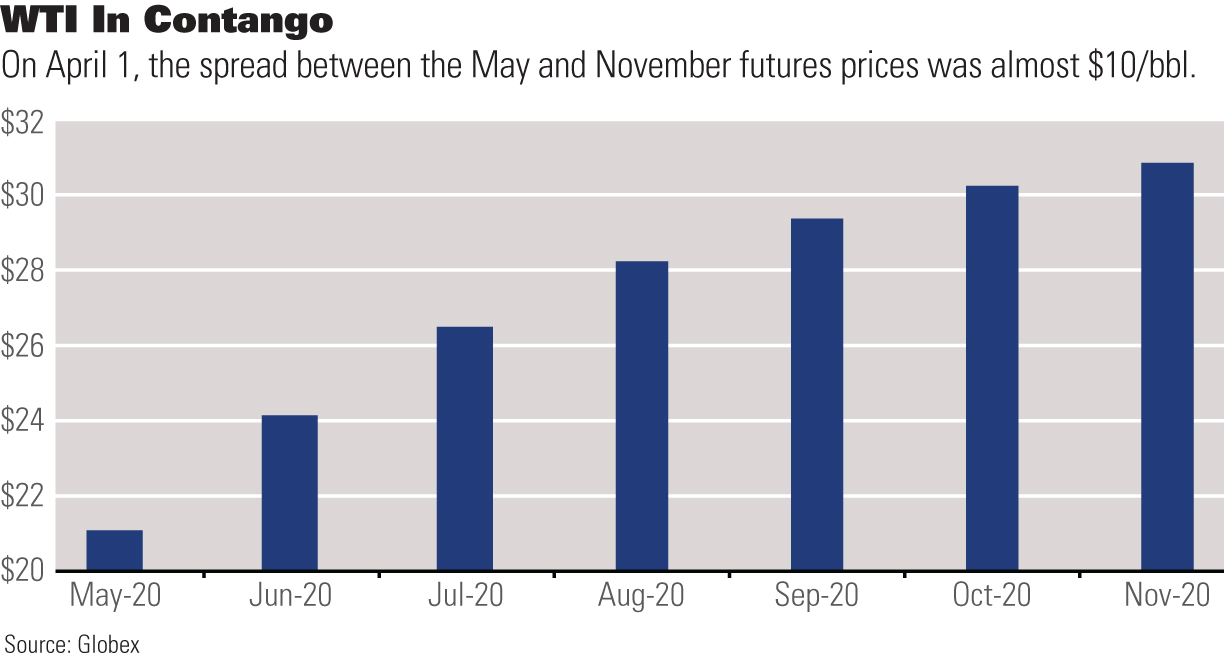

However, the market was signaling by late March that low prices could go beyond laying down rigs.

Bernstein Research noted that oil prices in the low $20s require “significant shut-ins to avoid inventories overflowing.” At prices of $25/bbl, low-producing vertical wells with high unit costs are uneconomical, Bernstein analyst Bob Brackett wrote in a March 27 report. About 120,000 such wells are found in the Permian, with about a quarter owned by Occidental Petroleum Corp., Apache Corp. and Pioneer Natural Resources.

In early April, Ryan Sitton, one of three RRC commissioners, said some Permian producers were “beginning to get offers at $6 per barrel” net, after differentials and transportation costs.

Keys said that at wellhead prices of $5/bbl few Permian wells would generate profitable margins, “and about half of the production in the basin would be getting negative margins. So negative cash flow.”

“When I talk about shutting in, there are a lot of people who tell me I shouldn’t be telling them what to do,” Keys said. “That’s not what I’m saying. If someone operates their assets at negative margins—thereby causing irreparable damage to their balance sheets—for long enough, out of stubbornness or ignorance, that’s obviously their choice. But I’d have to ask them the same thing if they were punching themselves in the face: why are you intentionally hurting yourselves?”

Keys said that if enough operators continue producing assets at negative margins, the rest of the industry will suffer.

“We all need to remember we are producing a commodity,” he said. “I think over the past six to eight years, we collectively forgot that.”

Read the rest of Oil and Gas Investor's "The Path Forward" special report:

Part 1: The E&P Survival Guide (story above)

Amid a pandemic and a disastrously timed OPEC+ supply war, executives, analysts and consultants advise hedging strategies, keeping a close watch on markets and, potentially, rebuilding business plans from the ground up.

Part 2: Full Reverse

Market forces are at competing odds, with a silent virus killing global demand for oil and foreign antagonists pushing more volumes into the supply pipeline. How does it end, and who wins—or just remains standing?

Part 3: OFS: Lower-for-Longer Scenario

As E&Ps jam the brakes on capex spend, the largest U.S. oilfield service providers respond in unison, cutting costs where they can and laying down equipment where they must.

Recommended Reading

Expand CFO: ‘Durable’ LNG, Not AI, to Drive US NatGas Demand

2025-02-14 - About three-quarters of future U.S. gas demand growth will be fueled by LNG exports, while data centers’ needs will be more muted, according to Expand Energy CFO Mohit Singh.

Trump’s DOE Issues First LNG Permit of Term to Commonwealth LNG

2025-02-14 - The former administration of President Joe Biden had halted permitting for all of 2024.

Bottlenecks Holding US Back from NatGas, LNG Dominance

2025-03-13 - North America’s natural gas abundance positions the region to be a reliable power supplier. But regulatory factors are holding the industry back from fully tackling the global energy crisis, experts at CERAWeek said.

US NatGas in Storage Grows for Second Week

2025-03-27 - The extra warm spring weather has allowed stocks to rise, but analysts expect high demand in the summer to keep pressure on U.S. storage levels.

Gulf South Pipeline Cuts Gas to Freeport LNG's Texas Plant After Lightning Strike

2025-03-24 - The incident has slashed gas usage at Freeport LNG's plant, which can process up to 2.4 Bcf/d of gas, to 450 MMcf/d from previous expectations of almost 1.8 Bcf/d, according to LSEG data.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.