China’s dominance of minerals used for energy transition necessities—particularly batteries—has prompted action, and handouts, from the U.S. federal government. But it still may not be enough.

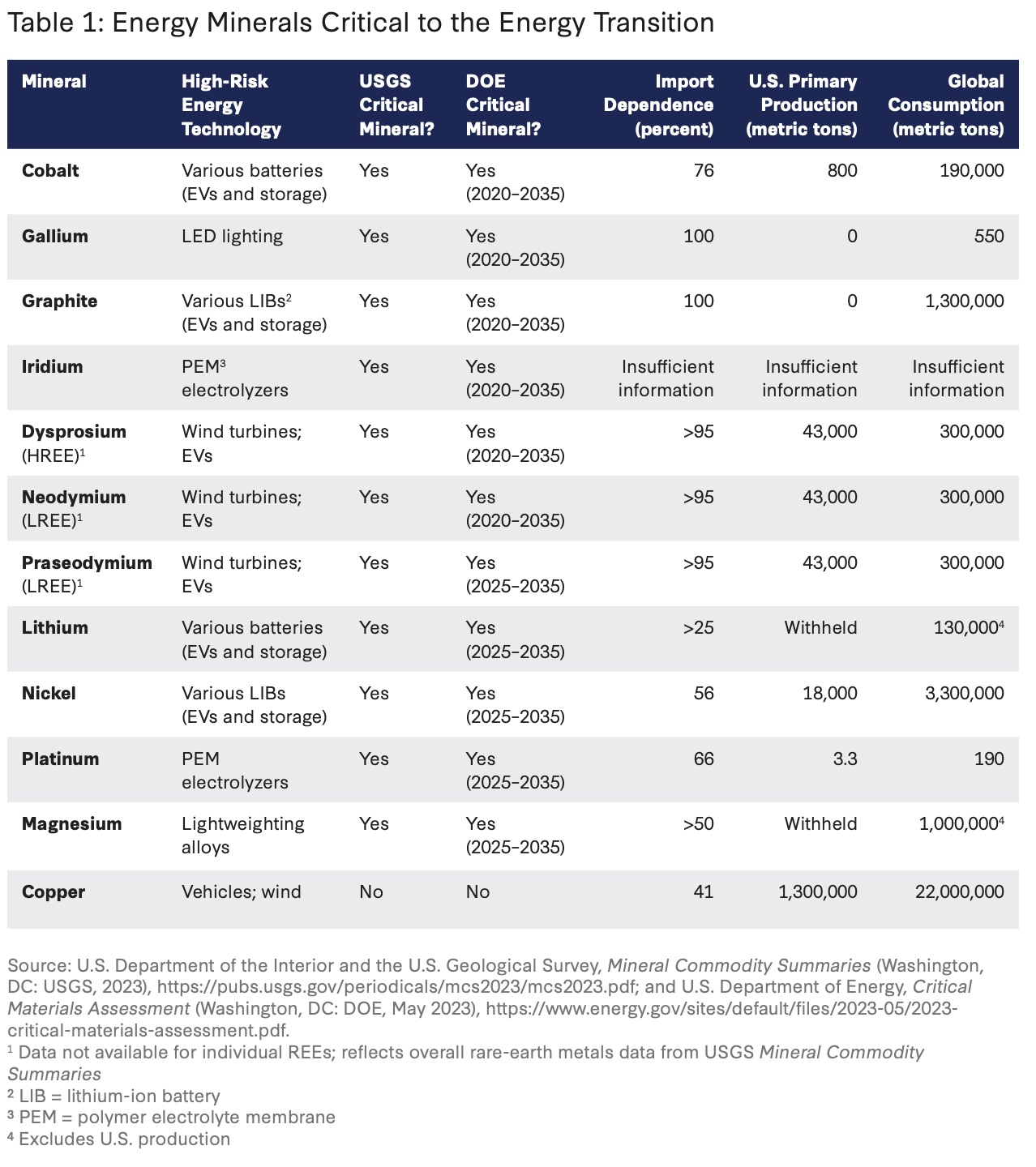

The U.S. has partnered with other countries to strengthen global critical mineral supply chains, rolled out tax credits for battery materials projects, extended tax breaks for critical minerals producers and awarded funds to advance technologies.

Still, meeting the demand for critical minerals won’t happen without private investment, experts say. That is something Frank Fannon, managing director for Fannon Global Advisors, said he is not seeing much of lately despite policy tailwinds that suggest otherwise.

“The main reason why is if you’re building a mine you have to anticipate what is the value of the commodity that you’re going to be producing 15, 20 years from now,” Fannon said during a recent event hosted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). “But if China controls the dominant supply, [it is] the price determinant of what that future outlook’s going to be. Until…we start to integrate some differentiation of pricing, I don’t know how we’re going to incent the things that we’re doing.”

Identifying solutions for the critical minerals challenge has been a point of discussion lately as the U.S. works to strengthen its supplies both domestically and abroad. The attention comes amid a continued push to lower-carbon energy resources in a quest to reduce emissions.

The pricing differentiation that Fannon referenced could be based on anti-corruption, human rights or environmental policy, or insight into supply chain transparency. Clarity and direction for investors could also come with more guidance from the U.S., specifically regarding domestic content requirements of battery materials.

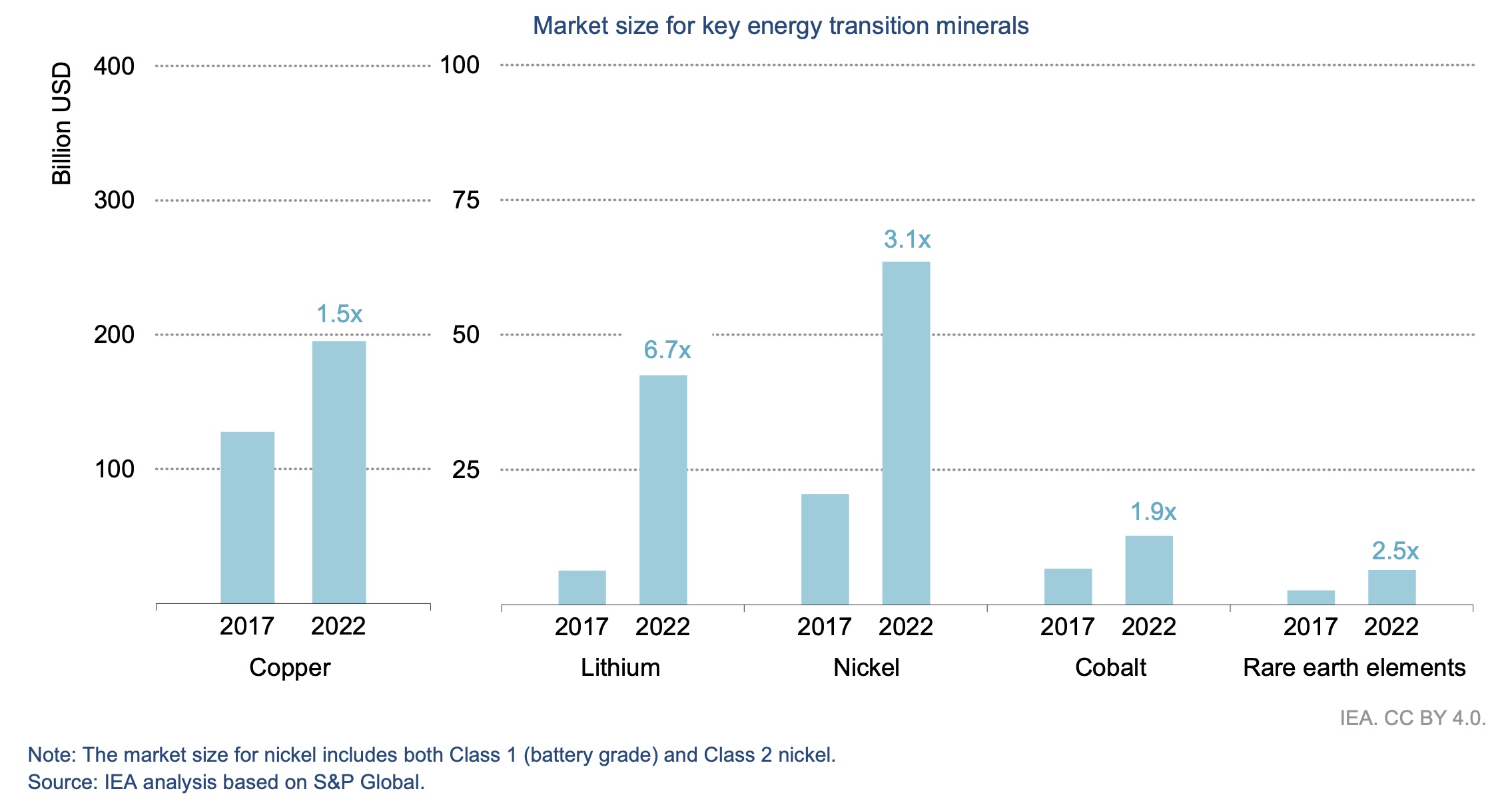

While governments establish policy frameworks and parameters, “the private sector executes,” Fannon said. “Exploration investment [in minerals] was only $13 billion last year. That’s from S&P. By contrast, the oil and gas industry, where we have demand-destruction policies, the investment was $500 billion, basically the value of the base metals industry as a whole.”

Investment lagging

As much as $450 billion in critical mineral mining investment will be needed through 2030 to reach net-zero goals by 2050, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), while critical mineral processing investments will need to rise to at least $90 billion.

CSIS pointed out in its minerals supply chain report that anticipated investments in mining account for about half of what’s needed, with expected investments in processing accounting for two-thirds of the need.

China dominates not only in critical minerals mining and processing but also investment—accounting for about 70% of the expected global investment—mainly in processing. In addition to developing its own resources, China has poured billions into minerals-rich countries, including the world’s top cobalt-producer, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Indonesia, home to large nickel reservices, according to the CSIS.

“Low price transparency and the illiquid nature of critical minerals markets is likely affecting investment decisions and keeping private capital on the sidelines,” CSIS said in its July mineral supply chain report. “Minerals markets are small and opaque, which limits both investor opportunity and confidence. There is no organized market on which to trade all forms of one mineral, making production and trade flows difficult to trace and mineral markets small. Even with an anticipated increase in demand, investors are faced with declining investment quality and high uncertainty.”

Added to these is the possibility of falling victim to fraud or buying worthless cargo, it said.

Something to consider

CSIS recommended improving data collection for risk analysis and scenario planning by authorizing the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Minerals Information Center, or another suitable federal agency, to collect and analyze data. Priorities could also be coordinated by a single federal entity such as a minerals-focused agency.

Another suggestion: add flexibility to prospecting tools, including expanding the domestic source scope in Defense Protection Act Title III to include Australia. The country has vast mineral reserves—including cobalt, lithium and manganese used in batteries. The U.S. could financially support Australia to grow its global supply chain.

To safeguard markets for growth, CSIS suggested commissioning a study on how to facilitate openness and fairness. The task could be led by the U.S. and its Minerals Security Partnership members.

“The United States can use its heft in the global financial sector and regulatory standards to help improve the transparency and quality of markets,” CSIS said in the report. “Safeguarding those markets for growth will encourage private capital to build upon the prospecting efforts of the United States and like-minded allies to build a more robust supply of minerals for the energy transition and, ultimately, national security.”

Getting off the sidelines

However, the problem isn’t just about getting private investment off the sidelines. Investment is also needed in places so far neglected by capital, said Abigail Wulf, vice president and director for SAFE’s Center for Critical Minerals Strategy.

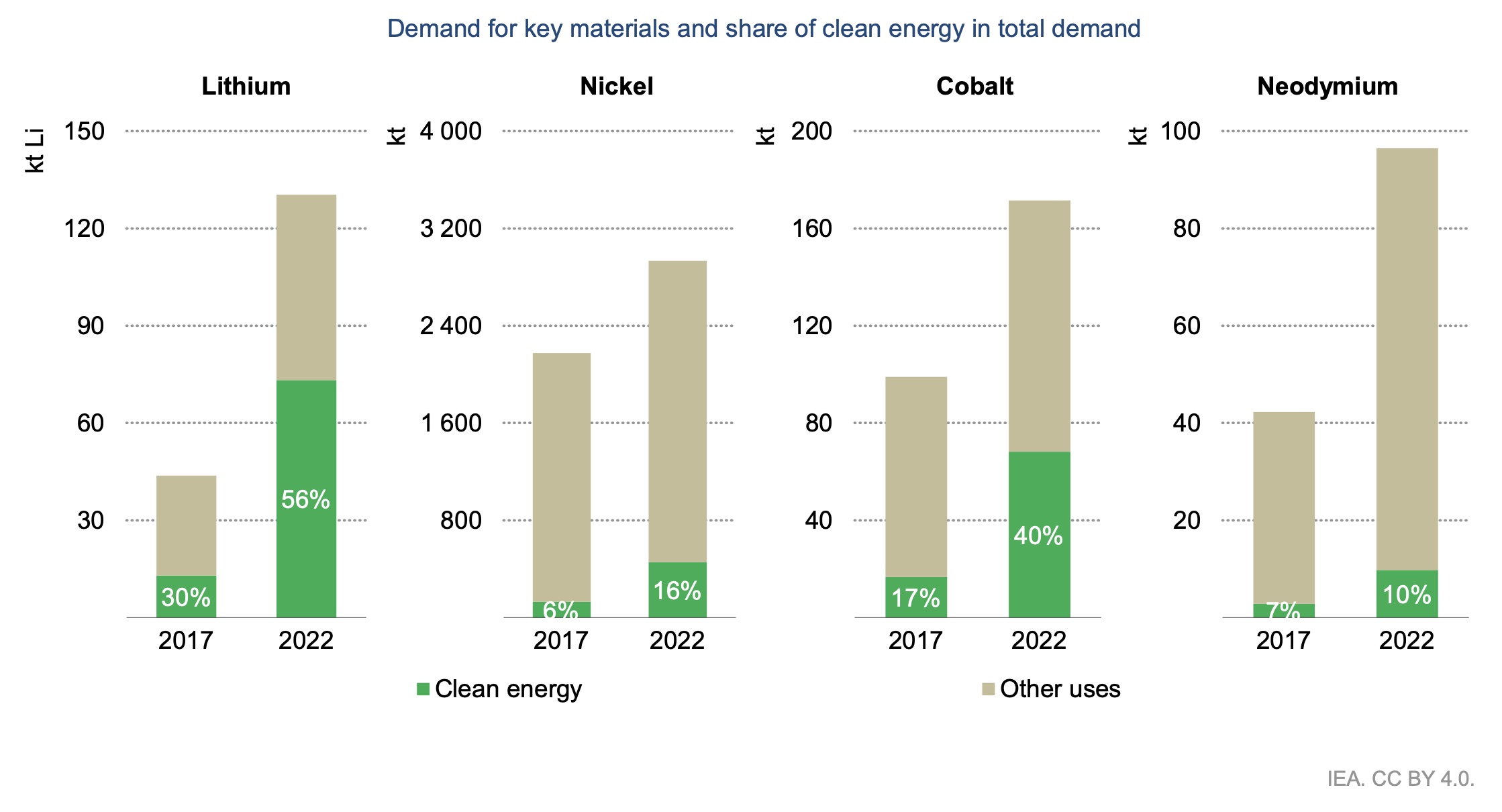

As mentioned in the recent IEA report on minerals, supply chains have become more concentrated for nickel and cobalt. “On top of that, ESG standards have not changed for greenhouse-gas emissions, water use and waste products,” she said.

Given that this is a free market economy and the U.S. government doesn’t mine or make products, “the strongest market signal we have right now is the Inflation Reduction Act, and within that, the clean vehicle tax credits, which stipulate where you can and cannot get things from to get that clean vehicle tax credit.”

Final guidance from the U.S. has not been released yet.

Wulf and others are eagerly awaiting word on what constitutes a “foreign entity of concern.” That is defined in the CHIPS Act, for example, showing how much Chinese content is allowed in the supply chain, she said.

“It’s also very difficult when you might be actually inadvertently punishing some of these first movers—innovative movers within the United States,” that are beyond the startup phase but aren’t far enough along in their journey to develop batteries, Wulf added. “So how can we make sure that we are simultaneously supporting those early movers … while also bringing up these new suppliers [and] not subsidizing our foreign competitors?”

Tech moving targets?

Besides policy and pricing risks, advances in battery chemistry are important when making investments, said Cullen Hendrix, state fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

“The materials that we are prioritizing now are not necessarily going to be the materials that the material scientists are going to be telling us we’re going to be needing 10 years from now,” Hendrix said.

Several battery technology companies are making progress and could pave new paths toward solving the critical minerals dilemma.

Form Energy Inc., an energy-storage company backed by Bill Gates’ Breakthrough Energy Ventures, is gearing up its iron-air technology working with Xcel Energy on a 10-megawatt demonstration-scale energy storage system in Minnesota.

Stellantis-backed startup Lyten is using abundant supplies of natural gas to help make lithium-sulfur batteries. The lithium-sulfur battery doesn’t contain nickel, cobalt or manganese, which are tight in the supply chain.

“The IEA is giving us great projections and they’re the best thing that we have to go on, I think, in terms of a shared consensus around what the future might look like,” Hendrix said. “But humans are notoriously bad at anticipating the results of technological breakthroughs and how that’s going to affect their current solution set to particular problems.”

Recommended Reading

Well Logging Could Get a Makeover

2024-02-27 - Aramco’s KASHF robot, expected to deploy in 2025, will be able to operate in both vertical and horizontal segments of wellbores.

E&P Highlights: April 22, 2024

2024-04-22 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including a standardization MoU and new contract awards.

Tech Trends: Halliburton’s Carbon Capturing Cement Solution

2024-02-20 - Halliburton’s new CorrosaLock cement solution provides chemical resistance to CO2 and minimizes the impact of cyclic loading on the cement barrier.

The Need for Speed in Oil, Gas Operations

2024-03-22 - NobleAI uses “science-based AI” to improve operator decision making and speed up oil and gas developments.

E&P Highlights: April 29, 2024

2024-04-29 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including a new contract award and drilling technology.