This rig was drilling for Encino Acquisition Partners in Ohio’s Utica play last fall. (Source: Ashley Unbehagen/Encino Energy LLC)

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the March 2019 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

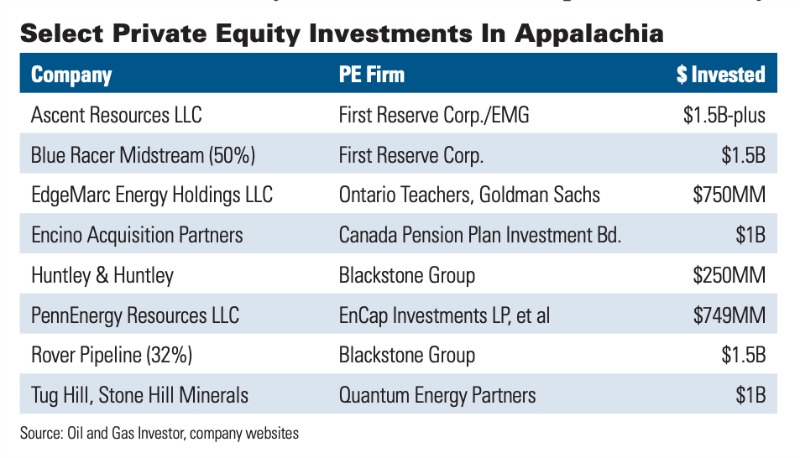

Just as out of acorns do mighty oaks grow, one phone call can jumpstart a multibillion-dollar E&P business. The phenomenon is certainly at work in the Marcellus and Utica plays, where private-equity leaders such as the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB), EnCap Investments LP, Quantum Energy Partners and The Energy & Minerals Group are backing some of the most growth-oriented E&Ps.

Such was the case for Hardy Murchison, CEO of Encino Energy LLC, which he formed in 2011. The Houston company had made a few smaller acquisitions and reduced costs on those properties. But in June 2017, Encino went bigger, much bigger, forming Encino Acquisition Partners with the CPPIB, which committed up to US$1 billion for doing onshore U.S. deals. Like most observers, Murchison fully expects to see further consolidation in the Appalachian region.

“As our chairman likes to say, acquisition is our middle name,” he said with a laugh. Encino’s executive chairman is legendary company-builder John Pinkerton, previously executive vice president of Snyder Oil Corp. and then chairman, CEO and president of Range Resources Corp., where Murchison once worked as vice president of corporate development.

After forming Encino Acquisition Partners (EAP) in 2017 with CPPIB, EAP closed its first major deal in October 2018, paying $2 billion in cash for Chesapeake Energy Corp.’s Ohio Utica assets. With more than 2,100 Utica locations identified that can yield an internal rate of return of at least 20%, with $2 gas and $50 oil, Encino is well on its way now, running two rigs this year and evaluating whether to add a third. It has the luxury of flexibility, because almost all the acreage is HBP, and the company can live within cash flow, Murchison said. One completion crew is working and Encino is adding another, he added.

Previously with private-equity firm First Reserve Corp. for 10 years, Murchison has helped establish several E&Ps in his career and always wanted to start his own one day, since working for Pinkerton at Range in the late 1990s. The EAP vision was simple: use long-term capital to build a large-scale E&P company, and exploit long-lived, low-cost assets held by production, but with a lot of running room. That description fits the Utica package to a T.

What’s more, Encino has assembled an experienced Appalachian dream team: in addition to Pinkerton, Tim Parker joined as chief technology officer. He had been COO of Dominion E&P Co. and executive vice president of exploration at Santa Fe Snyder Corp. as well. Recently, retired Range Resources COO Ray Walker joined Encino in the same role. Walker built Range’s Marcellus business, running up to 13 horizontal rigs at its peak. Michael Magilton, CFO, was previously with First Reserve Corp., Quantum Resources and Sabine Oil & Gas.

During the 2014 to 2015 downturn, Encino found competition to buy small asset packages surprisingly intense; that was when Pinkerton and Murchison pivoted to a much bolder vision.

“All we needed to do was raise a billion dollars, so I called Toronto,” Murchison said. The Canadian Pension Plan Investment Board, to be exact. Encino had started with a methodical process by talking to dozens of possible investors, figuring it needed a group because of how much capital it was targeting, but then CPPIB turned out to be a perfect fit.

It sounds casual, but the backstory is what made it feasible. “Naturally there is a lot of due diligence when you’re asking for a billion dollars, but at the end of the day, it was relationships and a shared vision that made the difference,” Murchison explained. “I had longstanding relationships with CPPIB managing directors Mike Hill and Avik Dey; Avik and I worked together at First Reserve, and Mike, who was at Deutsche Bank for much of that time, called on us quite actively.”

Because Encino sought small deals before 2016, CPPIB was not a fit then, “but when we decided on a strategic shift, suddenly the fit was there. And, it turned out to be a very opportune time in the business cycle,” said Murchison. “For one thing, they knew that among many sellers of big asset packages, Chesapeake Energy Corp. wanted to exit the Ohio Utica.

“With CPPIB we crafted a strategy—everyone was trending toward a single-basin focus and short-term investments. We decided that instead of raising shorter-term money or going public with a SPAC [special purpose acquisition company], we could use long-term capital and build a large company, somewhat in the mold of what John had done at Range or Tim had done at Dominion. They built multibasin asset portfolios through acquisitions, developed world-class technical teams and operations around them, and allocated capital rigorously between the assets. Both companies either paid dividends or lived within cash flow for long periods of time—their shareholders fared very well.”

Murchison said the Chesapeake Utica deal is only the first of what he hopes will be many. His vision for Encino is to operate in multiple basins with several large assets and the latest technology. “We have seen that model of combining top-notch technical and operating teams with rigorous capital allocation work,” he told Oil and Gas Investor.

This last downturn teed up the buying opportunity, Murchison admitted. But before the public markets began clamoring for free cash flow and returns, “we never changed from late 2016 when we started discussions with CPPIB—we always focused on full-cycle margins and return on capital employed.”

The team looked at the Permian and several other plays and at some of the largest asset packages marketed in the past two years. “This Utica asset kept rising to the top—it had large-scale production, low costs, cash flow and decades of development drilling ahead of it. It was well-delineated by a couple thousand horizontal wells and was almost all HBP.

“Think of 900 as a key number: we bought 900,000 acres, producing nearly 900 million cubic feet equivalent per day (MMcfe/d) from almost 900 horizontal wells. Chesapeake did an excellent job building this asset, but it just wasn’t capitalized to optimize it. They’d built a first-rate team in Ohio, but then couldn’t turn them loose to fully exploit the properties, so that’s our opportunity. We’re going in and applying longer laterals and a dedicated technical team, and we can make continuous improvements for years,” Murchison said. “Look at companies like Ascent Resources: they’ve clearly demonstrated that bigger completion volumes and longer laterals work in the Utica. Chesapeake experimented with these things, but we’ll take the asset to the next level …”

As chief technical officer, Parker “has explicitly adopted the philosophy that we’ll be as strong technically as an independent can be, and he’s building the team for that. We also had a blank slate with which to adopt the newest technologies and processes,” Murchison said.

“An example is type curves—we developed an in-house, multivariable regression tool that allows us to look at every factor, from geology to rock and fluid properties to landing points, completion parameters and any other variables that affect well productivity.

“Instead of applying half a dozen type curves in the Utica, we can forecast every location uniquely. It is a single-well forecast of hydrocarbons, fluid properties, reservoir parameters—everything for which there is data.”

“Instead of applying half a dozen type curves in the Utica, we can forecast every location uniquely. It is a single-well forecast of hydrocarbons, fluid properties, reservoir parameters—everything for which there is data.”

Encino will incorporate commodity prices, capital, operating and other costs into its analysis, then map individual well returns across the play, Murchison said. “We believe this approach to big data enables us to make better investment decisions.”

Encino has a long time horizon given its partnership with CPPIB, but Murchison said the E&P is building something “that could be extremely attractive in the public markets or for buyers. CPPIB’s appetite is larger than what we’ve done so far, so if we execute well, we have the opportunity to build a large onshore E&P company.”

By the time the deal closed, Encino operated some 865 producing horizontal Utica wells, most with high net revenue interest. It’s 70% gas by volume but about 50% liquids by revenue.

“What we bought is an array of acreage that spans the hydrocarbon windows, with exposure to crude and liquids. What had not been done consistently was applying longer laterals from multiwell pads, using slickwater fracks and high pump rates, so that’s what we’re doing,” Murchison said. “Recent results on our acreage are very encouraging. We’ll drill and complete between 40 and 50 wells this year.”

Encino has pipeline contracts to move all that it can produce to Dawn, Ontario, or to the Gulf Coast. While its marketers have the flexibility to take advantage of local price spikes that come with events like the polar vortex, the company can sell all its gas outside of Appalachia.

Murchison said he expects Encino to grow net production by 30% to 40% given its active development program. “Then assuming no growth through new pipeline outlets, we can hold production flat for two decades while generating strong free cash flow. That’s the beauty of a large, high-margin asset like this.”

And, he said the Utica remains ripe for further consolidation, and Encino has access to more capital. “We could reasonably expect to triple the size of the business through acquisitions.”

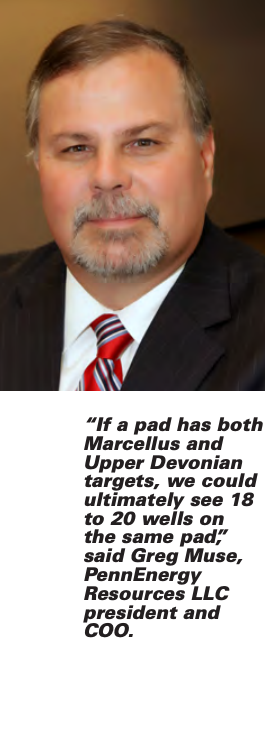

PennEnergy’s Growth

In 2010, Atlas Energy Resources LLC CEO Rich Weber lured a 28-year Marathon Oil Corp. veteran, Greg Muse, to join him at Atlas as COO. (Muse had first come to Pittsburgh to oversee Marathon’s Marcellus activity.) The pair engineered a $1.7-billion joint venture between Atlas and India’s Reliance Industries as the Marcellus began to boom—but later, Chevron Corp. came calling and bought Atlas. After that sale, Weber and Muse wanted to do it all again; the pair had overseen the drilling of more than 100 horizontal Marcellus wells.

At the same time, Weber connected with EnCap Investments, where he had met partner Jason DeLorenzo more than a decade earlier. In a familiar private-equity practice, EnCap’s team rightly figured that after having sold to a larger entity, these Atlas executives might want to have another shot on goal.

Sure enough, relationships propelled the discussions forward. Weber and Muse formed PennEnergy Resources LLC in 2011 and EnCap came in to the tune of a $300 million initial commitment. PennEnergy was to focus on three counties north of Pittsburgh.

Sure enough, relationships propelled the discussions forward. Weber and Muse formed PennEnergy Resources LLC in 2011 and EnCap came in to the tune of a $300 million initial commitment. PennEnergy was to focus on three counties north of Pittsburgh.

Fast forward to August 2018, when PennEnergy made another significant deal, paying nearly $571 million (after collateralized cash disbursement) to acquire the Pennsylvania assets of Rex Energy Corp. out of the latter’s bankruptcy. It took over operatorship of the assets (on mostly contiguous acreage) last October, and assumed all of Rex’s back office functions this past January.

“The acquisition was an ideal fit for us with numerous opportunities for synergies and significant reduction of overhead. We have fully integrated the assets, and it has gone very smoothly,” president and COO Muse told Oil and Gas Investor, “due to planning on both sides and full cooperation from the team at Rex.”

Post-close, PennEnergy is producing close to 530 MMcf/d gross of natural gas and 3,900 barrels per day (bbl/d) of condensate from approximately 350 wells. By the time wet gas is processed, total equivalent production is about 700 MMcfe/d gross from the combined assets. The company is operating two rigs this year (one horizontal fluid rig, the other an air drilling rig that opens up the first 2,000 vertical feet), and may pick up another horizontal in the second half, depending on gas and NGL prices. It expects to turn in line 41 wells this year and thus bring the total to 390 wells on production, Muse said.

“We have plans underway to be ready to pick up another horizontal rig, including the building of new pad locations. But right now our primary focus is on cash flow and maintaining a strong balance sheet,” Muse said.

The air rig is currently drilling on legacy wet-gas assets in Beaver County north of Pittsburgh and the horizontal rig is drilling in the dry gas area in Butler County. If a second horizontal rig is picked up, it will deploy on Rex’s Butler County acreage, he said. About 34% of production is NGL. With the newly added Rex acreage, the company’s production will be a bit more weighted to wet gas than dry on the whole, he said.

“We have very good economics in the dry gas area, and with oil and NGL prices having come down, the dry gas areas are competitive with the wet gas economics. Our three-year average finding and development cost is just 36 cents per Mcfe,” he said.

The company has a fair amount of stacked Upper Devonian upside above the Marcellus on its Beaver County acreage which is material, he said, even though it is not nearly as pervasive as the Marcellus is, basinwide. “We think completing six wells per pad is optimal for us, considering capital spend cycle times , with laterals of 7,000 to 8,000 feet being the sweet spot, although PennEnergy has drilled laterals as long as 10,000 feet. We do have some future laterals planned as long as 13,000 feet,” Muse said.

“If a pad has both Marcellus and Upper Devonian targets, then we could ultimately see 18 to 20 wells on the same pad, but not drilled all at one time. We’d plan to spread out the development over time such that we won’t have to come back to the pad for five or six years. We want to manage the total investment on one location, because the cycle time is so long already going in—to drill and complete as many as 18 wells at one time, you’d be well in excess of one year on the same pad. It would take several months just for the fracking.”

To minimize the parent-child effect on future reserve recoveries, PennEnergy leaves large areas open between developed wells such that future wells can be developed without significant negative impact to ultimate recovery.

The PennEnergy team keeps a close eye on technology; while not cutting edge, it likes to be fast followers that employ new technology once it has demonstrated success.

“We believe in the value of a lot of detailed planning—we are planning for our 2020 wells and beyond already,” Muse said. “Where margins could be low, planning and capital efficiency are all the more important, and that includes everything across all disciplines, such as better water management.”

PennEnergy has dramatically reduced water costs by between $500,000 and $600,000 per completed well since it laid a 5-mile line from the Ohio River to its Beaver County acreage and installed a central impoundment to cost-effectively pump water to multiple pads.

A further backstop is that the company has hedged 85% of its 2019 output and 50% of 2020’s anticipated production, he added.

Keeping The Pipes Full

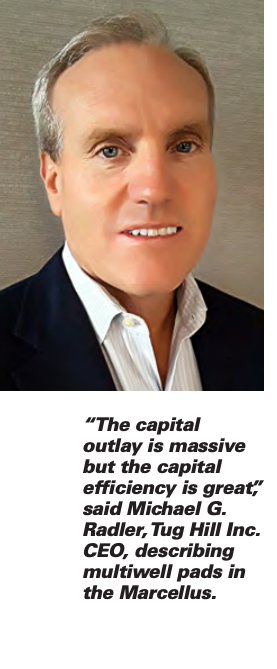

Privately held Tug Hill Inc., based in Fort Worth, Texas, has drilled or participated in more than 1,000 Marcellus wells, the bulk of them in northeast Pennsylvania through a partnership operated by Trevor Rees-Jones’ Chief Oil & Gas. They jointly own about 230,000 acres in the northeast corner of the state, with production of about 1 Bcfe/d gross, 110 MMcfe net to Tug Hill. Chief operates the asset and does all the gas marketing.

“Much of the gas is now flowing on our FT on Atlantic Sunrise. I believe any producers who have FT on Atlantic Sunrise are happy. We’re very excited because going forward, basis will not be as big an issue,” said Michael Radler, CEO of Tug Hill.

“Much of the gas is now flowing on our FT on Atlantic Sunrise. I believe any producers who have FT on Atlantic Sunrise are happy. We’re very excited because going forward, basis will not be as big an issue,” said Michael Radler, CEO of Tug Hill.

Atlantic Sunrise Pipeline, operated by Williams, has capacity to move 1.7 Bcf/d, with Cabot Oil & Gas holding 700 MMcf/d of that. Prices at Leidy, Pa., rose to more than $4 recently, more than double what they were before the new 183-mile line opened for business in October. It moves gas from northeast Pennsylvania to Dominion’s Cove Point LNG facility and other markets further south.

“The Northeast producers have learned their lesson—you drill to produce only as much as you have to, to supply your FT and nothing material beyond that,” Radler told Oil and Gas Investor.

“That goes for every operator you speak to. There’s no need to over-drill. The days of telling the equity markets to look at production growth, while ignoring returns, are gone. If a public company is spending outside its free cash flow, it gets beat up and its stock price reflects that. I think this has helped level the playing field for privately held companies,” Radler said.

“There are very few DUCs anymore, because in 2018 we saw a flurry of AFEs anticipating Sunrise going into service. But that has fallen off; if it’s a DUC [drilled but uncompleted well] today, it’s probably going to be a DUC forever unless it’s in an area with no midstream or access to markets.”

Radler said most operators in northeast Pennsylvania have settled on well spacing of 1,000 feet, with most wells drilled to the Lower Marcellus.

In 2011, Tug Hill and Chief sold the majority of their acreage in southwest Pennsylvania and West Virginia to Chevron. In 2014, Tug Hill established a new partnership with Quantum Energy Partners focused on southwest Appalachia. Today, they have three platforms (upstream, minerals and midstream) with a combined equity commitment of about $1 billion.

“I’ve known Wil [Quantum CEO Wil VanLoh] for quite some time; we’re friends. The energy business is a small fraternity,” Radler said. “When the decision was made to go with private equity, I went to Wil for advice on the various options and said, ‘Tell me who’s good and who’s bad,’ and he walked me through it. But he also said, ‘Before you decide, let Quantum have a shot at it.’”

Three-Dimensional Chess

The first of the three platforms, THQ Appalachia, is operated by Tug Hill. It has a consolidated block of over 50,000 net surface acres, 94,000 net formation acres, in Marshall and Wetzel counties, W.Va., where it’s pad drilling to the Marcellus and Utica/Point Pleasant with four rigs. It plans 16 Utica and 74 Marcellus wells there by year-end.

Current production of about 93 MMcf/d will rise to 450 MMcf/d by year-end and exit 2020 around 770 MMcf/d, Radler said. “We’re drilling both zones on pads in West Virginia and have been for quite some time due to the complexity of the topography. It’s proven to be the most efficient way to go and creates the highest EURs and economic returns.”

In addition to dealing with the topography, pad locations are limited due to area coal mines. THQ has to position its wells in a manner that allows drilling through the coal pillars to access the target reservoirs.

“We think of it like three-dimensional chess,” Radler said. “A tremendous amount of front-end planning and well design goes into it. It’s very complex with a lot of logistics.

“For example, the biggest pad we’re drilling now has 20 wells on it, and we’ve planned one that will have 28 wells. The directional plan for each well becomes critical and in some ways, it’s like drilling offshore. We’ve reduced D&C costs to what we believe are the best in the basin, and we’ve approached this in a very technical way, with sim-ops [simultaneous operations, that is, drilling, fracking and flowing production at the same time on the same pad].”

Radler said if not done this way, due to limited surface area for pads, there’s a likelihood the company could miss the opportunity to complete future wells in the Utica, due to poor pad design and directional well planning.

“Many operators don’t understand the Utica/Point Pleasant because early well costs have been so high. Our full-cycle returns in the Utica are over 40% using strip pricing, and that’s including land costs, G&A and everything. We have cracked the code on completing these wells in West Virginia, and we’re generating returns superior to Tier-1 dry Marcellus.”

Some THQ wells have laterals as long as 16,000 feet, but the average range is 8,000 to 11,000 feet, depending on the terrain, geology and lease lines. Optimum Utica well spacing is 1,250 feet.

Some operators have tried tighter spacing in southwest Appalachia, but Radler said he thinks 750 to 1,000 feet is the optimum for the Marcellus. Zipper fracks help retain the pay zone’s energy and yield a higher EUR, he said. “We know that if you really want to get the greatest recoveries by well, pad drilling and completions are the right answer to avoid depletion issues that have been seen in other basins from parent-child relationships, when returning to a pad at a later date.

“The capital outlay is massive, but the capital efficiency is great,” Radler said. “A lot of capital goes out the door, but in the end it pays off on many different levels.”

The second Tug Hill-Quantum platform is Stone Hill Minerals LLC, with has 25,000 net fee mineral acres in West Virginia and Pennsylvania, 25,000 net overriding royalty acres in Ohio and 59,000 net fee mineral acres in the Permian. These minerals have been strategically acquired in the most prolific areas of these basins and ahead of the drillbit.

Finally, there is XcL Midstream LLC, a rich- and dry-gas gathering and transportation system in Marshall and Wetzel counties, with extensions into Ohio and Pennsylvania planned in the near future.

Throughput is about 600 MMcf/d on the rich-gas side and 2.5 Bcf/d on the dry-gas side. It consists of two 24-inch pipes and various laterals that service THQ and third-party gas producers. “It interconnects to every major long-haul pipeline—Dominion, Columbia, Texas Eastern, Energy Transfer, etc., in southwest Appalachia. It’s the backbone for us—we can flow production to all these different points, which allows us to take advantage of the best gas markets and pricing,” Radler said.

Ascent’s Latest

The Energy & Minerals Group and First Reserve Corp. are the private-equity players backing Ascent Resources LLC, which has grown through a series of acquisitions, most recently the $1.5 billion purchase of Utica Shale assets when Hess Corp. and CNX Resources Corp. exited Ohio. Since the company was formed in 2013 it has become the largest pure play in the Utica. (For more, see “Ascent in the Utica,” Oil and Gas Investor, August 2018.) It has 310,000 net acres and has identified nearly 2,300 locations.

It’s in some of the best rock, where the play strengthens and is overpressured to the south with better permeability and somewhat higher porosity,” he said, in Belmont, Monroe, southern Jefferson and Guernsey counties. Some 210 wells are producing.

In January, CEO Jeff Fisher made the decision to reduce the number of operated rigs from seven to six “with plans to level out there, subject to significant shifts in commodity prices.”

In light of those changing prices for oil, gas and NGL, has the production mix shifted for Ascent? “No shifts, as we will maintain exposure to all phases, where our returns are robust and comparable. We will be leveraging our mineral ownership on a significant portion of our 2019 plan,” he told Oil and Gas Investor.

Last summer Ascent acquired Utica Minerals Development and assets from another undisclosed seller at the same time the Hess and CNX deals came to fruition. That added 60,000 net fee mineral acres, always a boon to economics. Achieving cash-flow neutrality is a priority for 2019 and Fisher thinks the company will succeed as it has “a strong line of sight given our execution and hedge book. We will start throwing off significant free cash flow in 2020 and beyond.”

All in, Ascent ended 2018 producing 1.8 Bcfe/d, right on target with projections, Fisher said. According to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, in fourth-quarter 2017, the company had 17 of the top 20 gas wells in Ohio—and it had this same track record per third-quarter 2018 ODNR data. “Our top-producing well averaged a choke-managed 32.5 MMcf/d, and we had 34 wells that averaged over 20 MMcf/d. We also were the top oil producer in the Utica at 20,000 bbl/d,” he said.

Good technology follows good rock, and since many of Ascent’s employees were formerly with Chesapeake Energy, technology is a focus.

“We see the rhetoric on optimized well spacing playing out with some of our peers, but from the start, we designed for 1,000-foot inter-lateral well spacing in the dry gas and 750 feet in the liquids-rich phases of the Utica,” Fisher said. “Our data continues to confirm these parameters. One operator in the Marcellus has recently stated they are moving from 750 feet toward 1,000 feet in the dry gas … we are already there.

“We continue to make positive strides on continuously improving our completion efficiency along every foot of the lateral using advanced techniques, including new core analysis and fiber optic technology.”

Fortunately given the rise in Ohio production, all major infrastructure that Ascent needs is in place, he said, with the company being an anchor shipper on the Rex and Rover pipeline systems. “We will look to further enhance connectivity within the basin amongst all of our takeaway pipelines to increase market optionality,” he added.

“We love the Utica. We’re focused on our program and repeatability, but we’re hitting on all cylinders.”

Leslie Haines can be reached at lhaines@hartenergy.com.

Recommended Reading

Waha NatGas Prices Go Negative

2024-03-14 - An Enterprise Partners executive said conditions make for a strong LNG export market at an industry lunch on March 14.

Summit Midstream Launches Double E Pipeline Open Season

2024-04-02 - The Double E pipeline is set to deliver gas to the Waha Hub before the Matterhorn Express pipeline provides sorely needed takeaway capacity, an analyst said.

Kinder Morgan Sees Need for Another Permian NatGas Pipeline

2024-04-18 - Negative prices, tight capacity and upcoming demand are driving natural gas leaders at Kinder Morgan to think about more takeaway capacity.

Enbridge Announces $500MM Investment in Gulf Coast Facilities

2024-03-06 - Enbridge’s 2024 budget will go primarily towards crude export and storage, advancing plans that see continued growth in power generated by natural gas.

Williams Beats 2023 Expectations, Touts Natgas Infrastructure Additions

2024-02-14 - Williams to continue developing natural gas infrastructure in 2024 with growth capex expected to top $1.45 billion.