Construction of natural gas pipelines is unlikely to keep up with Permian Basin production, which will lead to increased flaring, a report by East Daley Analytics and Validere says. (Source: Shutterstock.com)

Infrastructure constraints in the Permian Basin will likely result in an uptick in flaring during the next surge of production growth, a May 23 report predicts, which will draw increased environmental scrutiny to oil and gas producers.

Even the infrastructure projects under construction, such as expansions of Kinder Morgan’s Permian Highway and the MPLX-WhiteWater Midstream joint venture’s (JV) Whistler pipelines, and the newbuild Matterhorn Express Pipeline – a JV of WhiteWater, MPLX, EnLink Midstream, Devon Energy – will not be sufficient to handle the expected growth.

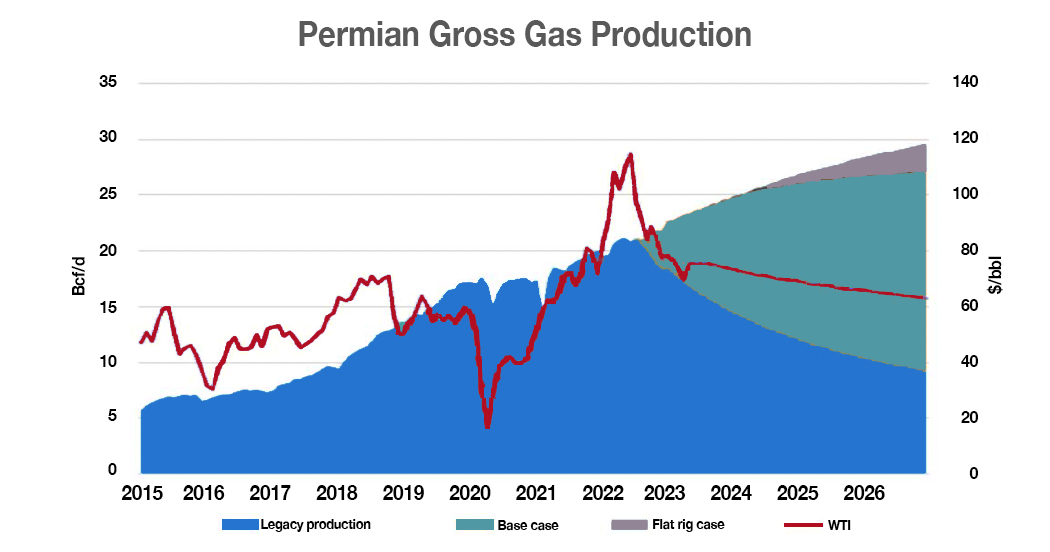

“After peaking in 2019, East Daley Analytics estimates that excess gas production has steadily fallen as new capacity accommodated production growth,” the report said.

That trend will reverse between now and the end of 2026, East Daley and Validere said in the co-authored report, “Flaring, methane, and the cost of looming Permian gas takeaway constraints.”

More production, more flaring

East Daley presents three scenarios tied to commodity prices, planned pipeline expansions and Permian production that would impact flaring:

Base case: The backwardated forward curve drives down rig counts and productivity improvements do not offset the decline. Excess gas production mostly stays low but spikes to about 500 MMcf/d just before the Matterhorn Express Pipeline is brought online in mid-2024.

Flat rig case: Rig counts stay flat and excess gas production doubles through the report’s time frame, ramping significantly in 2026 if new takeaway capacity is not added.

Less drilling, delayed pipelines: Under-construction expansions for the Permian Highway and Whistler pipelines are delayed by three months, and the Matterhorn Express is delayed for six months.

If producers do not further reduce drilling, excess gas production would spike dramatically to more than 800 MMcf/d at year-end 2023 and 1.6 Bcf/d at year-end 2024.

The analysts acknowledge that a dynamic and volatile commodity market itself generates uncertainty about future production growth. That affects plans to expand pipeline capacity and, therefore, flaring levels.

While the Williston Basin in North Dakota has been plagued with flaring issues for years, the Permian is more vulnerable, the report said. As more wells are connected to the grid in the Williston, that gas will largely displace Canadian supplies. For that reason, the basin does not require additional takeaway infrastructure. The Permian does.

“Relative to other basins, the Permian is most at risk of intermittent flaring increases because of where it sits in the gas pipeline grid,” the report said. “No gas supply flows into the region, meaning that Permian growth requires expensive new pipeline capacity development.”

However, the process of building that needed infrastructure is not an easy one.

Steve Pruett, president and CEO of Elevation Resources and chairman of IPAA, agrees that infrastructure is inadequate, but notes the difficulty of building more.

“If you have 25 [MMcf/d] going through … five compressor stations and they’ve got 25 [MMcf/d] of capacity and one goes down—which happens about every third day—then you’re to be flaring 5 [MMcf/d] unless you shut in the wells,” Pruett said May 22 at Hart Energy’s SUPER DUG conference. “So, the answer is redundancy, but the question for the midstream player is: Do I want to invest that money in the redundancy?”

The operator needs capital to buy the equipment, but also an air permit to install it. On the Texas side of the Permian, that is not a problem; on the New Mexico side, it is.

“New Mexico is a totally different, tougher regulatory landscape,” he said. “It’s very difficult to get the permits to add capacity, whether it’s a processing plant—especially if it’s for sour gas—or whether it’s for compressor stations. So that is an impediment to building the redundant capacity we need for 99.9% online reliability, which, in turn, reduces flaring.”

Flares don’t always work

Additional takeaway capacity is not expected to be in place when production ramps up, so some producers likely will opt to flare. That can have ramifications for the industry.

When flares work as designed, they are critical safety devices and valuable in emissions control. Combustion efficiency is typically higher than 98%, so less than 2% of the gas escapes into the atmosphere.

But as Validere analysts note in the report, the flares often fail to meet that standard. Flares have been observed to be completely unlit, meaning that 100% of the gas is pumped into the atmosphere. There have also been instances when the equipment exhibits degraded combustion efficiency, meaning that the gas emitted can be much higher than 2%.

A 2020 aerial survey of the Permian by the Environmental Defense Fund reported that 11% of flares had combustion issues. A 2022 study by researchers from the University of Michigan and Stanford University concluded that flaring efficiency was only 91%.

Validere does not agree with the conclusions, noting that flare volumes are not evenly distributed across all flares. Flares at newer, higher-producing wells are less likely to operate with degraded combustion efficiency, so the aggregate across the Permian is likely better than the 91% to 93% range of the studies.

However, even 97% efficiency results in an extra 500,000 tons of CO2 emitted into the atmosphere each year, the report said. That is the kind of statistic that fuels environmentalists’ ire.

“With Permian flaring levels likely to rise, operators in the basin will face increased environmental scrutiny,” said Jen Snyder, senior adviser at Validere. “It will be more important than ever to monitor both new and old flares, to ensure that this increase in flaring doesn’t also cause a sharp uptick in methane emissions, which has a much bigger near-term climate impact.”