Excess natural gas is burned off at an oil well site in the Permian Basin. (Source: Sean Hannon/Shutterstock.com)

When it comes to reducing the amount of associated gas vented or flared in the Permian Basin, the size of a company doesn’t matter, according to panelists speaking during a recent symposium that put flaring back in the spotlight.

As pressure builds for oil and gas companies to reduce emissions, focus has returned to capturing the value of flared and vented associated gas. Experts at a recent natural gas flaring symposium hosted by the University of Houston say it is cost-effective for producers to mitigate routine flaring, calling it low-hanging fruit.

“My message is size is not an excuse,” Jennifer Stewart, vice president of strategic growth for Avitas, a Baker Hughes Co. venture, said of oil and gas companies during the symposium.

Amid a global push toward net-zero goals, investors of public companies in recent years have been calling on producers to cut emissions. Backers of some small and privately-held independents are now calling for the same, Stewart said, singling out those in the Permian Basin where smaller and private equity-backed producers outnumber public companies.

“They see the same risk that the shareholders of Chevron see: that environmental risk is investment risk,” she said using the oil major as an example. “They don’t want greenhouse gas. … They want to see what are your actual emissions and they want to see improvement.”

Avitas, which provides asset integrity management services, carries out automated and remotely monitored inspections using cameras, sensors and autonomous aerial and crawling robots among other services, according to its website. The company’s current projects include using drone-based inspection technology and data analytics for a privately-back Permian Basin producer seeking granular emissions data.

Though some have argued that costs associated with mitigating or abating flaring would force some smaller producers to shut in wells, particularly when infrastructure plans have not been made, a study released earlier this year by Rystad Energy and the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) revealed many solutions are not cost-prohibitive.

The study found that about 84% of routine flaring volumes and 40% of total flared volumes in the Permian Basin could be avoided at no cost to operators if Texas adopted a 98% gas capture policy, said Colin Leyden, director of regulatory and legislative affairs for the EDF.

Capturing Value

Whether it’s fugitive methane emissions or flaring, Leyden said, “the one good thing…is you do have a product that has some value. Now, it may not have as much value as the industry would like, but it does have value.”

“This is the low hanging fruit and the most cost-effective way to mitigate on climate that we know of, and that’s because that gas has some value.”

The Rystad study found that operators could realize an additional $400 million of wellhead value by 2025 if regulators required 98% of gas produced to be captured.

“There’s money to be made,” Leyden said.

Still, the economics are complicated.

“Do I spend a million dollars mitigating flaring and methane, or do I spend a million dollars to drill a new well?” he asked. “What are the people who I answer to really wanting?”

The export market could provide guidance.

“The European Union right now is considering methane standards for the gas that they purchase,” Leyden said.

He referenced the move by French gas and power utility Engie SA to pull out of a major U.S. LNG import deal with NextDecade Corp. last November citing government concerns about the contract’s environmental implications.

“We saw a contract for an LNG contract canceled by the government of France for a Texas contract, citing Permian emissions as being too high, including flaring,” he said. “Despite the rhetoric from some against how insignificant that contract may or may not have been, I think it points to a trend, which is as more countries assess their own carbon footprint and their use of fossil fuels, they’re going to want to be assured that fossil fuels they are using are as clean as possible.”

Many companies already see the benefit, having set sights on ending routine flaring by 2030.

Improvement in flaring rates has been made by the industry, Leyden acknowledged.

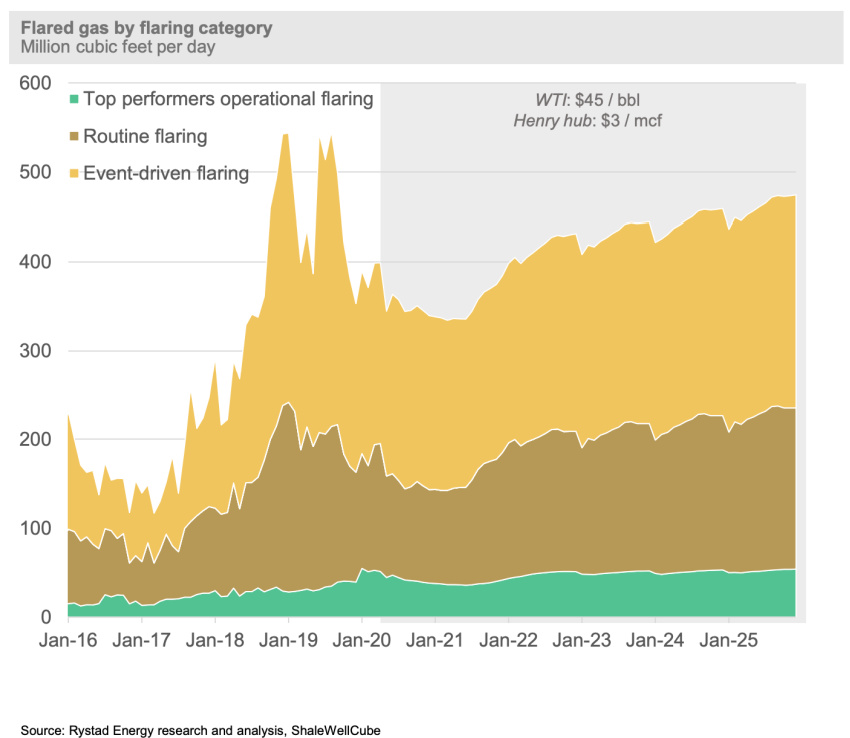

Flaring intensity, which is the ratio of flared gas volumes to gross gas produced, in the Permian Basin dropped to 2.8% by year-end 2019. That was down from a peak of 5.2% in 2018 when gas gathering and takeaway infrastructure failed to keep pace with rising production.

Flaring volumes fell further in 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic slowed global energy demand, prompting producers to shut-in wells. As a result, oil and gas activity was reduced, particularly from new wells—which Rystad Energy data show is the source of most routine flaring in early production months.

“Under a no-policy change assumption, total flaring is forecast to revert to 2019 volumes by 2025 (yearly average of about 460 MMcf/d),” according to Rystad.

The Texas Railroad Commission (RRC), however, has taken steps to wrangle routine flaring. In February, commissioners deferred applications from several oil companies seeking permission to flare gas. Late last year, they made changes to a data sheet, requiring companies seeking exception to the flaring rule to more thoroughly document the need to flare gas and provide the RRC accurate information to assess compliance.

Targeting Emissions

Many producers have reduced flaring, capturing gas value, without being mandated to do.

The Texas Methane & Flaring Coalition, comprised of trade associations and over 40 operators, announced in February a goal of ending routine flaring in the state by 2030.

RELATED

Texas Trade Coalition Aims to End Routine Flaring by 2030

Texas Railroad Commission Advances Flaring Regulation Efforts

Permian Basin Flaring Puts Value of Natural Gas in Spotlight

Leaders in the flaring reduction arena include Pioneer Natural Resources Co., EOG Resources Inc., Chevron Corp. and Occidental Petroleum Corp. These particular companies all have flaring rates of about 1% or less, a separate 2020 study on best practices in the Permian showed. Parsley Energy, which was later acquired by Pioneer, also had a low flaring rate at 2.5%

Stewart pointed out that Pioneer and Parsley were small companies, compared to Chevron, yet still managed to keep flaring in check. She noted that Parsley, earlier in 2020, had acquired private equity-backed Jagged Peak Energy, which had a “horrible environmental stewardship record” with a 20% flaring efficiency. Still, Parsley managed to keep its flaring rate low after the acquisition.

How did Parsley and others accomplish that? The so-called silver bullets, she said, were setting an aggressive flare intensity goal while not taking a one-size, fits-all approach. This requires tying compensation metrics to flaring performance goals and having strong governance from the board down to the field level.

Tanks, which are used to temporarily store oil or condensate, are another major source of emissions at production facilities, according to Susan Stuver, R&D manager at the Gas Technology Institute. Gasses in the tanks will vaporize, or flash.

“As the liquid level in the tank starts to fluctuate, these vapors are often vented to the atmosphere, unless there’s a vapor recovery unit that can either capture the gas and send it directly to the pipeline or can send it to a containment or the gases will go to a flare,” Stuver said.

The flares are designed to combust 98% of the methane in natural gas, she explained; however, if a flare is not adequately designed to handle the amount of gas it’s taking, the methane may not fully combust. “So, the combustion efficiency of that flare goes down.”

Sometimes hatches on tanks aren’t latched properly, allowing emissions into the air, she added.

However, Stuver noted several ways to combat emissions.

“We can optimize flare combustion efficiency by doing things like changing operating parameters, things like steam-to-vent gas ratios. We can add supplemental fuels or we can change the fuel-to-air ratio,” she said. “However, the ability for flare operators to achieve a high flare combustion efficiency is really limited by the lack of live flare efficiency data in order for them to respond to.”

Getting Creative

If abatement is the goal, replacing flares with something better like getting stranded gas into a pipeline or using it to generate electricity onsite are options, Stuver said. Infrastructure expenses are a barrier.

Still, she said producers are already getting creative with modular technologies or scalable systems, “even mobile systems that can move around to different sites.”

“We can go beyond just producing power with this gas. We could also produce things like methanol, which can produce gasoline. We can produce CNG, which is compressed natural gas, or LNG, which is liquefied natural gas, and that makes the investment in the infrastructure a little bit more economically feasible.”

Leyden wondered whether loss of power experienced in fields during the recent Texas freeze could point to an opportunity for gas-to-power in the Permian. Meanwhile, Stewart noted that some of these technologies are expensive.

“If you make a commitment to sell your gas before you put your well online,” she said, “there’s no need to explore those technologies.”

“Chevron said the best technology is not flaring all,” she added.

Regardless of the cost, more oil and gas companies are doing what they can to lower emissions, panelists said.

More companies want a place at the table in the emissions reduction and decarbonization space, Stuver said. “We, the industry, want to be part of that solution.”

Recommended Reading

SunPower Appoints Garzolini as Executive VP, Chief Revenue Officer

2024-03-14 - Tony Garzolini will oversee SunPower’s sales, including the direct, dealer and new homes channels, along with pricing and demand generation.

TPG Adds Lebovitz as Head of Infrastructure for Climate Investing Platform

2024-02-07 - TPG Rise Climate was launched in 2021 to make investments across asset classes in climate solutions globally.

JMR Services, A-Plus P&A to Merge Companies

2024-03-05 - The combined organization will operate under JMR Services and aims to become the largest pure-play plug and abandonment company in the nation.

Chord Energy Updates Executive Leadership Team

2024-03-07 - Chord Energy announced Michael Lou, Shannon Kinney and Richard Robuck have all been promoted to executive vice president, among other positions.

First Solar’s 14 GW of Operational Capacity to Support 30,000 Jobs by 2026

2024-02-26 - First Solar commissioned a study to analyze the economic impact of its vertically integrated solar manufacturing value chain.