Presented by:

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in Capital Formation 2021, a supplement to the May 2021 issue of Oil and Gas Investor magazine. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

“The oil and gas industry is always out of money. It just inhales capital.” That was what Joe Bridges said me when I interviewed him back in 2012 for my book, “Oil Capital, The History of American Oil, Wildcatters, Independents and Their Bankers.” Bridges should know; over the past 50-plus years, he’s been a roustabout, a banker, a CFO and founder of an oil and gas company. His observation is as true today as ever.

If you think the COVID-19 pandemic has lasted a long time, talk with a U.S. producer about the depressed energy capital markets. As Americans sat down for their Thanksgiving dinner in 2014, the Saudis declared they would no longer act as swing producer to prop up world oil prices, and the price of crude oil dropped 10% before the pumpkin pie hit the table. Producers and their lenders have been suffering under a pandemic of world energy prices ever since.

Tsunami of bankruptcies

As reported in Haynes and Boone LLP’s December 2020 “Oil Patch Bankruptcy Monitor,” more than 250 oil and gas producer bankruptcies have been filed since January 2015. Combined with midstream and oilfield service Chapter 11 filings since 2015, more than 500 bankruptcies have been filed.

During this dismal period, 2020 stands out, breaking a number of records. Last year accounted for more than 30% of the total $175 billion in secured and unsecured debt reported in producer bankruptcies since 2015. Last year also saw an increase in billion-dollar bankruptcies. Fourteen cases were filed last year compared to $54 billion filings during the total six-year period. Multibillion-dollar cases were filed by Chesapeake Energy Corp., Ultra Petroleum Corp. and Unit Corp., each involving more than $5 billion in aggregate debt.

More importantly for commercial banks and other secured lenders, the percentage of secured debt to total debt involved in producer bankruptcies increased substantially from 35% in 2016 to 46% in 2020. Earlier in the cycle, many banks were shielded from loss because of the large cushion of junior unsecured and second lien debt. Although not entirely unfazed by the first tsunami of bankruptcies, most commercial banks were made whole with exit financing provided to these early reorganized producers. But as the cycle continued its “lower for longer” course, the heat shield of junior debt was burned through by 2020, and senior lenders who had avoided feeling the pain of producer bankruptcies started racking up substantial losses.

Bankruptcies illustrate lenders’ new reality

The disclosure statement for Gulf of Mexico producer Arena Resources Inc. estimates that the senior lenders will recover roughly between 10% and 20% of their outstanding $600 million loan principal, depending upon contingent payments due under the sale of assets to San Juan Offshore LLC. First lien lenders in the Sanchez Energy Corp. bankruptcy saw no recovery at all, and even the lenders who provided financing to get the company through the bankruptcy process took a hit on their debtor-in-possession loan. Approach Resources Inc., following an initial failed sale, subsequently sold its assets paying its first lien lenders 27.5% of their $307.4 million principal. Ursa Resources lenders only recovered 11% of their $160 million original debt. These are some of the more extreme examples. However, there are a number of other producer bankruptcies where the senior lenders failed to come out whole.

This recent upset leading to losses on senior RBLs was unheard of historically. In 2013, Standard & Poor’s rating services reported that between 1996 and 2005 the recovery rate on senior secured bank debt in the E&P sector was excellent. S&P reported that going back to the mid-1990s less than 1% of bank loans greater than $50 million to the oil and gas industry had defaulted, and the recovery rate was nearly 100%. Despite the collateral’s volatility, oil and gas loans had been viewed as relatively safe loans. Given energy bankers’ recent experience, their senior credit committees have been reassessing their rosy outlook, changing their approach to underwriting and documenting RBLs.

In this context of unprecedented and unexpected loss of principal on multiple RBLs it is no surprise that producers are facing stiff headwinds in search of new bank capital either to refinance existing facilities or for new acquisitions and development. Prior to OPEC’s Thanksgiving turkey, bankers were freely supplying producers with capital—the oxygen they needed to grow and thrive. During the past two years, the same bankers have had their hands deep in their pockets with a tight grip on their purse strings. Combine this dearth of bank capital with the nonexistent public debt market during the past year, it is no wonder that 46 producers with over $53 billion of debt filed for bankruptcy in 2020.

Given this bleak background, what does it foretell for producers and their bankers in 2021?

No appetite for energy

The market is experiencing a bit of 1980s déjà vu as many banks exit the space altogether. In the 1980s, nine of the 10 largest Texas energy banks were either closed or forced to merge with healthier out of state banks. While banks in the energy space today are nowhere close to risk of failure, many have lost their appetite for energy loans.

Whitney Bank sold most of its $500 million energy portfolio last year to Oaktree Capital Management at a 50% discount. Huntington Bancshares and Texas Capital Bancshares are reportedly actively marketing their energy loan portfolios. Cadence Bank and Prosperity Bank have also re-evaluated their energy loan portfolios. The Bank of Montreal, one of the foreign energy banks with the longest presence in Houston since 1962, announced last November it was exiting the U.S. oil and gas space to concentrate on Canadian producers. European banks are doing the same, in part due to the recent losses, but also because of regulatory, political and investor concerns over funding hydrocarbon projects.

A significant number of the larger national and international bulge bracket banks have formally announced policies against funding Arctic exploration, and others have stated their intention to exit the fossil fuel space by 2050. In response, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency issued a proposed rule last November that would require banks to show they were not discriminating against oil and gas borrowers. This proposed rule has been put on pause pending review under President Joe Biden’s administration.

The energy bank sandbox is also getting smaller. Some of the leading syndicating banks are actively reducing head count. Other banks are being absorbed, thereby reducing the overall number of potential banks for producers to call on. SunTrust Bank and BB&T Bank merged at the end of 2019, First Horizon Bank acquired Iberia Bank in July and PNC Bank will finalize its merger of BBVA Compass this summer.

In the past, bank consolidations lead to a reduction in overall capital availability. After the ’80s bank consolidations, Chase Manhattan had acquired other energy banks—Manufacturers Hanover, Chemical, Texas Commerce and First City. But Chase preferred to stay with its original hold level and did not automatically aggregate the lending limits from each of the merged banks when making new energy loans.

While there will be new market entrants looking to fill the void, for example, Modern Bank out of New York with a Dallas office, fewer energy banks reduces competition and will make it harder to syndicate larger loans (i.e. more expensive for producers).

On the positive side, coming into 2021 commodity prices, particularly oil, have improved significantly. Public debt markets are reopening for healthier public producers.

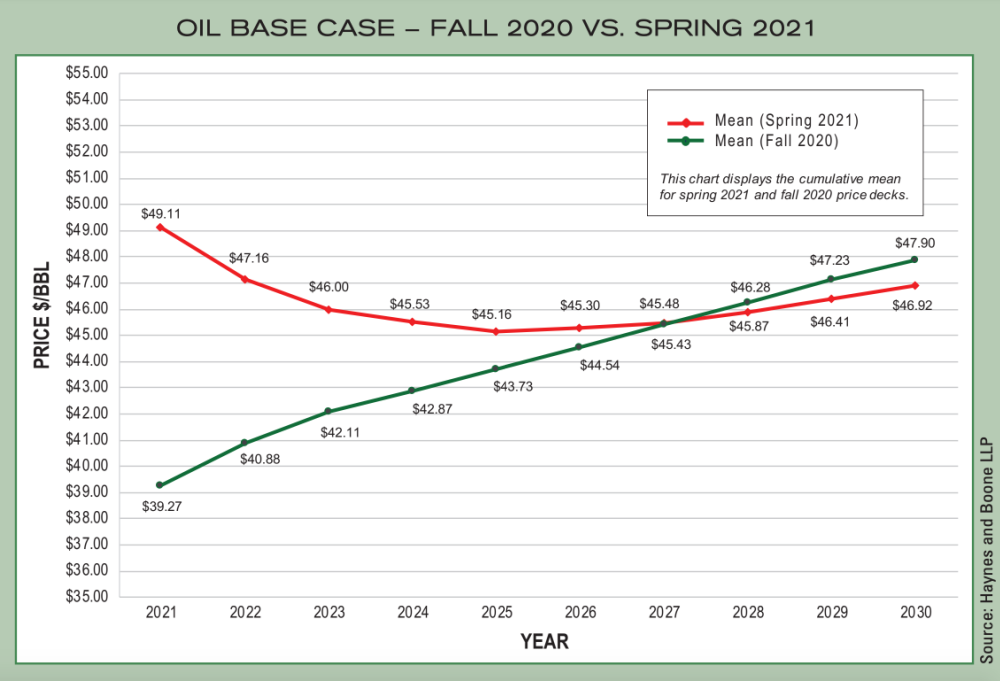

Spring borrowing bases

On the positive side, coming into 2021 commodity prices, particularly oil, have improved significantly. Public debt markets are reopening for healthier public producers. And the commodity uplift should help raise many of last year’s borrowing bases out of the basement. Of course, borrowing bases are a product of not just commodity prices but also a producer’s reserves. Lower credit availability and investor induced capital discipline for the past couple of years have led to a decreased in drilled and completed wells. This may translate to lower PDP this spring. If so, rising commodity prices in the $60 bbl range may not be enough to raise producers’ borrowing bases as much as may be expected.

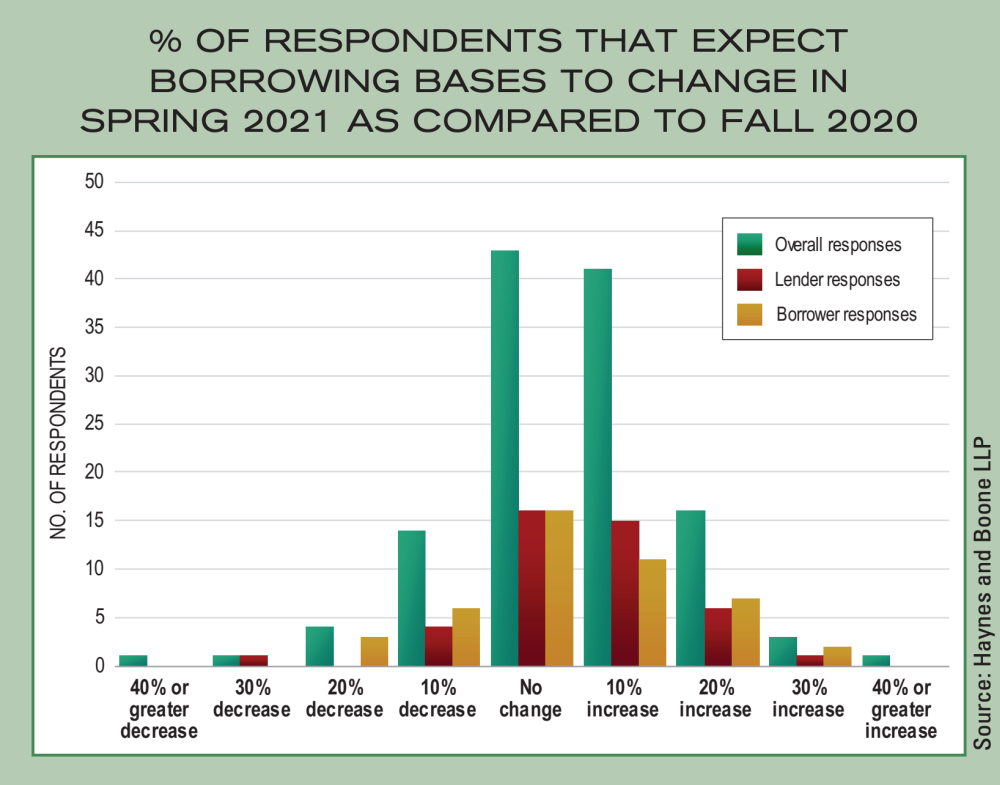

Haynes and Boone’s spring 2021 Borrowing Base Survey reports that industry participants expect a rise over last fall borrowing base determinations. Considering the hits that some producers saw in their 2020 borrowing base redeterminations, it will take a more significant rise before some producers get back to pre-2020 borrowing base levels.

Last summer, the Wall Street Journal reported borrowing base cuts to Centennial Resource Development Inc. from $1.2 billion to $700 million, Oasis Petroleum Inc. from $1.3 billion to $600 million, Antero Resources Corp.’s base was cut from $4.5 billion to $2.85 billion. Bruin E&P Partners LLC and Jonah Energy LLC saw their commitments cut below the actual amount drawn, requiring them to repay the deficit within six months. Bruin filed for bankruptcy soon after. Further dampening optimism for significant borrowing base relief this spring, the consensus among energy bankers is they are no longer giving any value to anything other than PDP. The days of booking 20% of PUD reserves to juice the borrowing base are gone (at least for now). Bankers are even discounting PDP reserves more than had been the norm before the crash. All in, if the industry as a whole sees flat borrowing base redeterminations this spring, that should be considered a victory for the producers.

Producers faced with uncertainty over their spring borrowing bases can be certain the cost of money and loan conditions will be more expensive over the near term. In light of their recent losses, banks have been repricing their RBL risks by increasing pricing not only for new loans, but under amendments to existing facilities by margins between 25 basis points (bps) and 75 bps.

Last year, Southwestern Energy and Talos Energy Inc. both reported their facility pricing was increased by 25 bps, Laredo Petroleum Inc. reported a 50 bps increase and Centennial Resource Production LLC and Penn Virginia Corp. reported increases of 75 bps and 100 bps, respectively. Borrowers that took a hit to their borrowing base last year may be paying even higher interest. Under the RBL pricing grid, the higher the usage of available funds, the higher the applicable margin for interest. If the borrowing base is reduced but outstandings remain the same, the usage percentage goes up and pricing follows.

Producers looking for credit in 2021 will also see tighter covenants. In particular the debt to EBITDA leverage covenant has narrowed from above 4.0:1.0 pre-collapse to today, 2.5:1.0, or below. Reduced leverage hurdles also translate into greater restrictions on distributions, making it harder (and taking longer) for equity investors to see a return on their investments. This has had a direct impact on private equity appetite for sponsoring new management teams. Banks have also reintroduced anti-cash hording provisions limiting the amount of cash on hand that a borrower can have at any one time and requiring liens on all of the producer’s operating accounts.

Related to their greater attention on cash producing assets (i.e., PDP reserves only), banks have increased mortgage and title coverage requirements to 90% or more of proved reserves. And to provide greater protection against any further downslide in commodity prices, energy bankers are requiring that producers hedge a higher percentage and for longer periods than previously.

Environmental, social and governance

If the increased costs of obtaining bank capital wasn’t enough to discourage producers from calling on their local bankers, there is a new issue de jure for the parties to cover. In speaking with a banker recently, it was noted that every bank deck presentation he is seeing from producers today has at least one slide, if not more, covering the company’s strategy to maximize its “ESG quotient.” However, the definition, yardstick and industry bar of what ESG means to a company whose sole business plan is to explore and produce hydrocarbons is not fully developed. For now, it behooves producers to be aware that this is a subject lenders want to cover. Producers should monitor what others are doing and be prepared to respond to a banker’s question how the producer intends to address the “ESG issue.” Haynes and Boone in conjunction with EnerCom Inc. recently launched the “Oil & Gas ESG Tracker,” evaluating stated ESG policies of 30 public mid-market onshore U.S. producers, which can provide some insight into current industry efforts.

Like Joe Bridges, most producers are optimists to the core. Producers and their bankers are seeing greenshoots this spring rising from the end of the world oil price pandemic, hopefully along with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although it will be more expensive to get senior bank financing, and the loan agreements will be tighter than years past, there is reason to expect that this too shall pass. John Templeton said the four most expensive words in investing are “this time it’s different.” As long as bankers and their credit committees remain fresh with the memories of the past six years, they will want to continue to hold fast to their new credit discipline and avoid repeating the mistakes of the past. But anyone who has been in the oil business for more than one cycle knows that as prices heat up, so too does the competition among banks to make loans.

Just as oil prices go up and down, so too does the pricing and covenants of RBLs. It is a safe prediction for producers who can withstand today’s pain, that bank pricing will fall and covenants will relax, until the cycle begins anew.

Buddy Clark is co-chair of Haynes and Boone LLP’s energy practice in Houston. Since graduating from University of Texas law school in 1982, he has focused his practice on reserve-based lending. In 2016, he published the definitive book on the history of oil and gas lending, “Oil Capital, The History of American Oil, Wildcatters, Independents and Their Bankers.”

Recommended Reading

Tech Trends: Halliburton’s Carbon Capturing Cement Solution

2024-02-20 - Halliburton’s new CorrosaLock cement solution provides chemical resistance to CO2 and minimizes the impact of cyclic loading on the cement barrier.

Exclusive: Carbo Sees Strong Future Amid Changing Energy Landscape

2024-03-15 - As Carbo Ceramics celebrates its 45th anniversary as a solutions provider, Senior Vice President Max Nikolaev details the company's five year plan and how it is handling the changing energy landscape in this Hart Energy Exclusive.

E&P Highlights: April 8, 2024

2024-04-08 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including new contract awards and a product launch.

ShearFRAC, Drill2Frac, Corva Collaborating on Fracs

2024-03-05 - Collaboration aims to standardize decision-making for frac operations.

The Need for Speed in Oil, Gas Operations

2024-03-22 - NobleAI uses “science-based AI” to improve operator decision making and speed up oil and gas developments.