The EU’s 27 member states were unprepared for the natural gas crisis unleashed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Now, it faces a challenging future. (Source: badwiser/Shutterstock.com)

The European Union (EU), caught off-guard by the energy fallout from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, responded effectively, legal experts said during a recent webinar.

Whether the 27 member states are able to maintain those budget-straining policies through the winter remains uncertain, however.

“In the bigger picture, member states are not united on how to go forward,” Leigh Hancher, a professor of European law at Tilburg University in the Netherlands, said during the event hosted by the Institute for Energy Law.

“It’s not so easy for the EU’s 27 member states to find a single voice,” Hancher said. “And that’s really a big issue. It’s not just because they are politically divided, of course, across the member states, but their dependency on gas varies very much.”

What they have in common, she said, is the need to import.

Suddenly Storage

The EU’s energy policy rests on three pillars:

- An internal market to encourage competition and affordability for consumers;

- Security of supply, meaning consumers should not be concerned that electricity will not be available when they turn on the lights; and

- Climate change, or clean sources of energy that are sustainable.

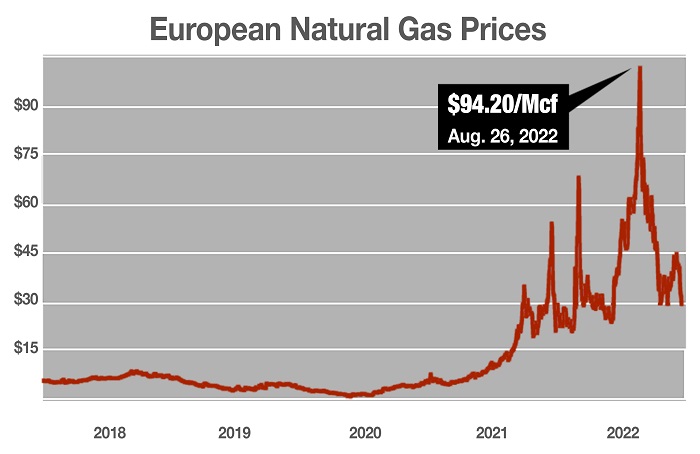

With the advent of the war in Ukraine, security of supply took on an entirely different meaning because the internal market could no longer be assured that external fuel would flow into it. Storage all of a sudden became a chief concern. And storage of natural gas was low.

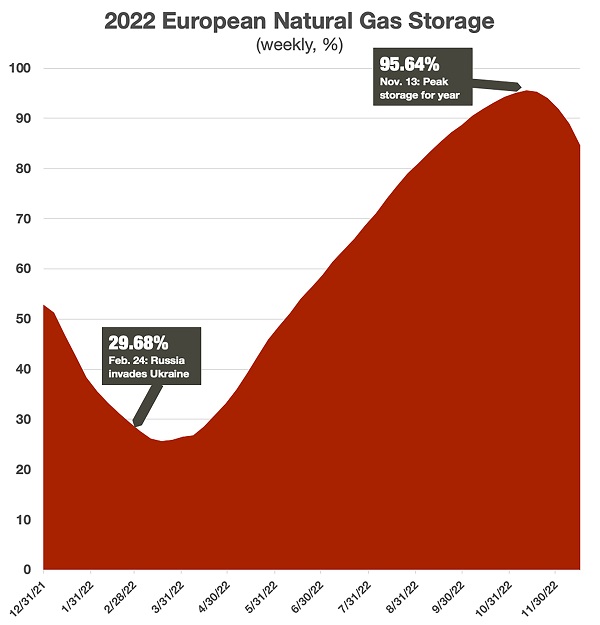

Inventory was just below 30% of capacity on the day Russian forces crossed into Ukraine on Feb. 24. By March 19, it had sunk to a low for the year of 25.5%.

That led to a concerted effort during the summer to refill natural gas inventories, no matter the cost. The goal, to reach 85% of capacity by the start of winter, was exceeded by September. But that only covers winter 2022-2023.

“The big problem is next year, if not ’24 as well, because we’ve lost about 40-50% of our gas supply coming from Russia, and the chances of making that up in the near future are slim, to say the least,” Hancher said.

Europe benefited from a mild autumn, Reuters said, which may help avert a natural gas crisis this winter. European countries were able to keep filling up gas storage until Nov. 13. It was the latest date recorded and 18 days past the median date for 2011-2021.

‘A Bit Blind’

Tension among European nations over how to achieve energy policy goals long predates the Ukraine war. Efforts to mitigate climate change ran up against the need for fossil fuels, manifesting in squabbles over construction permits for the Nord Stream 2 pipeline to bring Russian natural gas to Europe.

“The situation in the energy markets hasn’t been great to start with and, obviously, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has exacerbated the problems that we already have,” said Anna Butenko, legal manager for system operations at European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity (ENTSO-E) and senior research fellow at the Institute for Energy and the Environment at Vermont Law & Graduate School.

Ironically, Europe had been lulled into a sense of energy complacency because Gazprom, the Russian gas supplier, had been a reliable partner for many years, Butenko said. The concept of energy weaponization was relegated to academic discussions until recently.

In retrospect, it is easy to see the cutoff of Russian gas to Europe, she said. Even with Russian troops massing on Ukraine’s border, the prevailing belief was that it was a political situation to be resolved.

“Europe has been a bit blind to the impact of the potential loss of that supplier,” Butenko said. “I don’t think anybody could have imagined what was going to happen and that Russia would weaponize its energy to that extent.”

The result is a paradigm change, Butenko said. EU policymakers’ previous definition of an energy crisis was a pricing or supply issue affecting a single country. The legislation now in place is simply inadequate to manage a crisis of the magnitude that struck the region this year.

European leaders, she said, now must grapple with balancing the three pillars of their energy policy while figuring out how to pay for natural gas in the short term and sustainable renewable energy in the long term. A positive lesson from this past year, Butenko said, is that leaders have shown they can take necessary steps when needed.

“Europe … can move relatively fast,” she said. “We have seen this with the recent proposals and with recent changes with the power (system) in the EU.”

Recommended Reading

Honeywell Bags Air Products’ LNG Process, Equipment Business for $1.8B

2024-07-10 - Honeywell is growing its energy transition services offerings with the acquisition of Air Products’ LNG process technology and equipment business for $1.81 billion.

TGS Awarded Ocean Bottom Node Data Acquisition Contract in North America

2024-07-17 - The six-month contract was granted by a returning client for TGS to back up the client’s seismic data capabilities for informed decision making.

ProFrac, IWS Taking the Garbage Out of Oilfield Data Transfer

2024-07-16 - ProFrac and Intelligent Wellhead Systems’ MQTT protocol promises to speed up communications at the frac site, not only by saving costs but laying the foundation for future technological innovations and efficiencies in the field, the companies tell Hart Energy.

E-wireline: NexTier Taps Oilfield Grid, Automation for Completions

2024-07-23 - NexTier Completion Solutions is using advanced electric-drive equipment, automation-enabled pump down technology and digital connectivity to optimize wellsite operations during shale completions.

How Generative AI Liberates Data to Streamline Decisions

2024-07-22 - When combined with industrial data management, generative AI can allow processes to be more effective and scalable.