The goal of the oil and gas industry is to extract oil from the ground, transport and store it, and distribute it to the masses for consumption. This has been the status quo since the 1800s, yet it appears that many companies are leaving too much oil—and in turn, money—on the table.

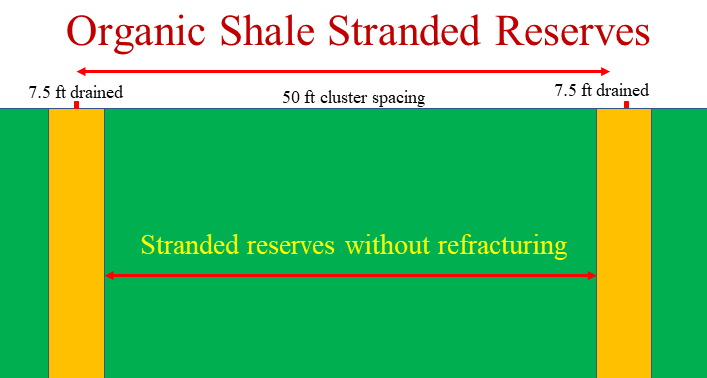

“We see a big discrepancy between the potential for refracs, with 36,000 wide coastal spacing candidates in the U.S. right now, and yet there’s only a handful of refracs,” Bob Barba, partner at Triple R Energy Partners, said during Hart Energy’s Super DUG event. “Out of the 100 operators in Eagle Ford, 90% have not done refracs. And out of all the operators in the Permian, about 0%, as far as we can tell, have done it.”

Despite the reluctance of many in the industry, Barba views refracs as the “real deal,” specifically in the Eagle Ford play. And while companies might shy away from refracking basins as a result of operating in chalk or more brittle rock, that doesn’t need to be a worry.

“As far as what I’ve seen, there hasn’t been any reservoirs that haven’t responded to [refracking],” said James Segars, director of solutions engineering at Universal Pressure Pumping. Segars has experience operating refracs in both shale and chalk basins, such as the Niobrara. He continued, “Obviously, some of them respond differently to the intensity of the fracture than the ultimate productivity of the well, but I would say at least from the overarching scenario, most [basins] should respond favorably.”

However, just because most basins should respond favorably doesn’t mean all of them will. And there are other concerns as well, including cost. Development costs are typically lower on newly drilled areas than they are on refracked reservoirs, Mark Pearson, president and CEO of Liberty Resources, told the audience.

“Go back three years ago, we were pretty happy if we’re pumping 12 hours a day. Now we’ve got to be pumping 20 hours a day to really set benchmarks. Those efficiencies have really decreased the overall development cost of the place that we’re currently in. I guess from my mind, it’s kind of the balance between deployed capital,” he said. “Do you go for the kind of the sure thing with the new DNC or do you look at it as you bring refrac opportunity?”

But despite his wariness around refracking, Pearson admits that it will likely soon become the norm. “I think as drilling inventory depletes, refrac is ultimately going to have to be where we go,” he said.

One way to mitigate some of the concerns around refracking, Barba says, is to adopt a process called “protective refracking,” which restores pore pressure in the parent well.

“There’s huge potential for refraction and you’ll see [refracs] work really well,” Barba said. “We’ve got enough wells to know they work, and yet they’re the most underutilized technology.

“Basically, it’s a normal refrac, but what it does is, it restores the original core pressure in the parent well and gives you enough stress cage, and that’s why you want to do it. At the same time, you don’t want to do it a month before. You want to have that pressure there in real time so you’ve got that wall.”

According to Barba, the biggest problem with unprotected child wells is the size of their depletion zones. Depletion zones are typically around 350 feet wide, but fracs can reach 1,000 feet. Walls in basins like the Eagle Ford are only three or four feet apart and “as soon as it sees that depleted zone, it’s going to stop growing on the distal side” which is where the lost reserves are, Barba said.

Recommended Reading

Electric Hype vs. Hydraulic Reality: Advantages of Traditional Systems

2024-05-07 - Castrol's new fluid prevents gas hydrates in deepwater control systems.

E&P Highlights: May 6, 2024

2024-05-06 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including technology milestones and new contract awards.

US Oil, Gas Rig Count Falls to Lowest Since January 2022

2024-05-03 - The oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, fell by eight to 605 in the week to May 3, in the biggest weekly decline since September 2023.

Pemex Reports Lower 2Q Production, Net Income

2024-05-03 - Mexico’s Pemex reported both lower oil and gas production and a 91% drop in net income in first-quarter 2024, but the company also reduced its total debt to $101.5 billion, executives said during an earnings webcast with analysts.

Woodside’s GoM Trion Project Wins Social Impact Assessment Approval

2024-02-14 - Woodside Energy’s Trion is expected to start production in the Mexican sector of the Gulf of Mexico in 2028, and Woodside said the impact assessment will help the operator engage with local communities during the construction phase.