Dennis Kissler, senior vice president of BOK Financial's trading division at Hart Energy's DUG Appalachia conference in Pittsburgh on Nov. 29. (Source: Hart Energy)

A day of reckoning is coming for regions that aggressively moved away from fossil fuels and undercut their ability to handle the demands of harsh weather, says a leading energy trader.

“I think New England has dodged a bullet because they’ve actually seen mild winter followed by mild summer and a mild winter to the start of this year, as well,” Dennis Kissler, senior vice president of BOK Financial’s trading division, told attendees of Hart Energy’s DUG Appalachia conference in Pittsburgh on Nov. 29. “If we see some kind of weather event that eventually we will have, I think they’ll be caught off guard, there’ll be brownouts, they’re going to realize they’re going to need another source of power.”

New England is not alone in its self-imposed energy vulnerability, Kissler said. Europe paid a steep price for its overdependence on Russian natural gas after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The subsequent loss of most of its imported supply was mitigated by U.S. producers shipping as much LNG to Europe as they had the previous six years, he said.

Europeans were able to pay the higher price for LNG diverted from Asian markets, but that in itself triggered another problem, Kissler said. China and India responded to the tight global market for gas by issuing permits for hundreds of new coal-fired power plants.

Shortly after Kissler finished speaking, Reuters reported that India planned to add 17 gigawatts of coal-based power generation capacity in the next 16 months to keep up with a record rise in power demand. Since 2016, the country cut back on plans for coal-fired plants in favor of cleaner energy sources.

“Asia turned to more coal, though they were trying to convert more to cleaner energy,” he said in his presentation. “[The impact of the war] scared them, as it should have. They become more dependent upon coal. That’s where you see all those coal plants came into play and continue to get bigger.”

Driven by policy

The policy-driven energy transition has run into supply-and-demand speed bumps. Kissler cited the experience of France, which has been a leading consumer of nuclear power. In 2022, 12 of the country’s aging 56 plants, representing 23% of its nuclear power generation, had to be shut down to repair cracked pipes.

France, an electricity exporter, was forced to import electricity from Germany, which generates 34% of is power from coal. Germany also relies on wind power for 25% of its electricity output, but Kissler noted that executives from BP and Siemens who said that the wind power sector is unprofitable, even with subsidies, and that financing for new projects was getting tougher and tougher.

“So, what’s left?” he asked. “If we’re going to take everything green or go to the green side, it’s going to have to be LNG or it’s going to have to be natural gas.”

With Russia an unreliable supplier as long as Vladimir Putin is in charge, the question would seem to center on U.S. LNG export capacity and its ability to grow rapidly. On this count, Kissler is bullish.

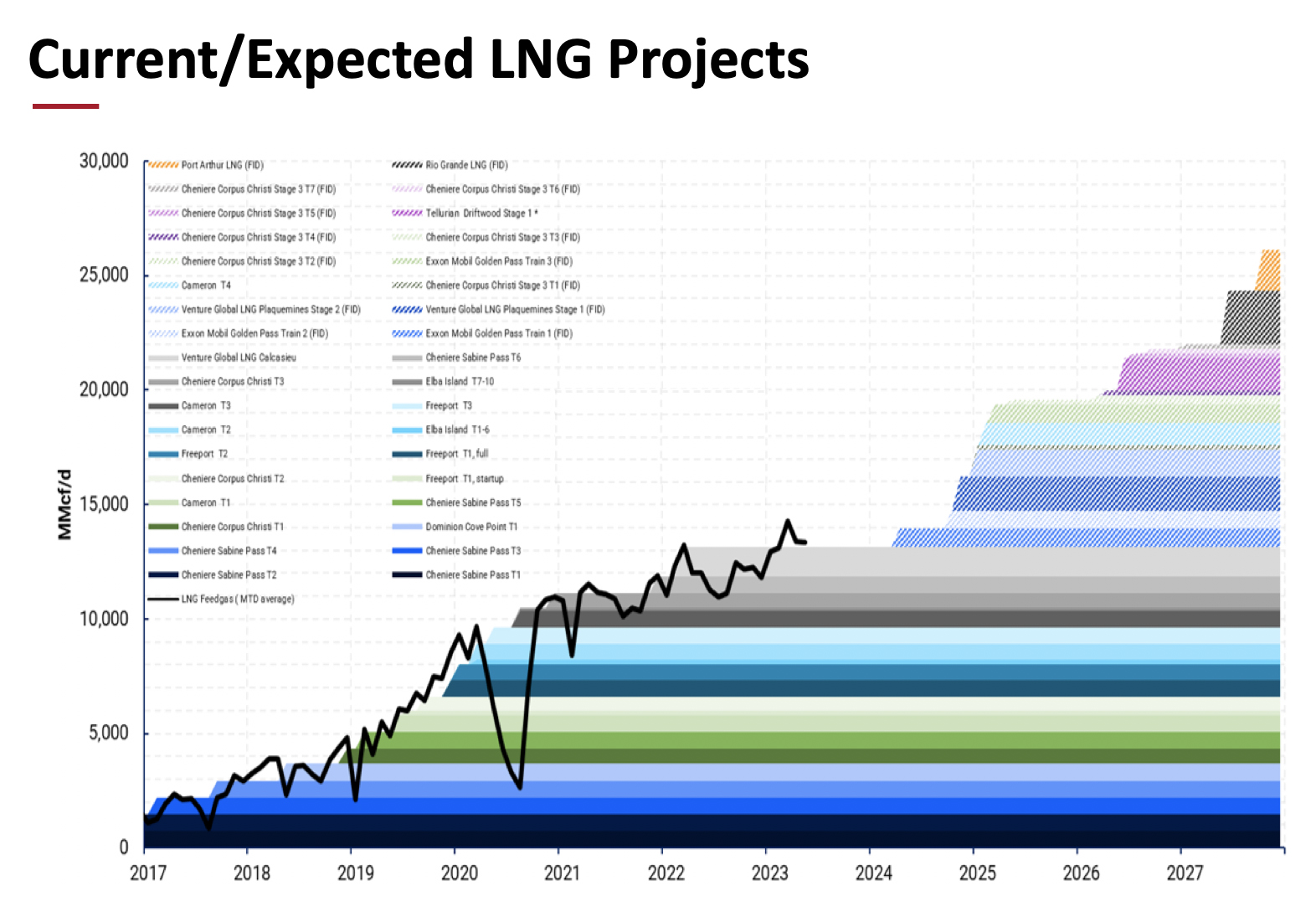

Expectations for U.S. LNG exports in the next few years call for an increase in the range of 11.5 Bcf/d to 12 Bcf/d, he said.

“We think by Q4 of ’26, we could see LNG exports somewhere north of 20 Bcf/d,” Kissler said. “That’s going to be quite a bit more than what’s projected on this graph. But again, I think it’s going to ramp up that quick.”

That’s because satisfying both the demand for electricity and Europe’s need for greener sources of energy points to natural gas as the answer.

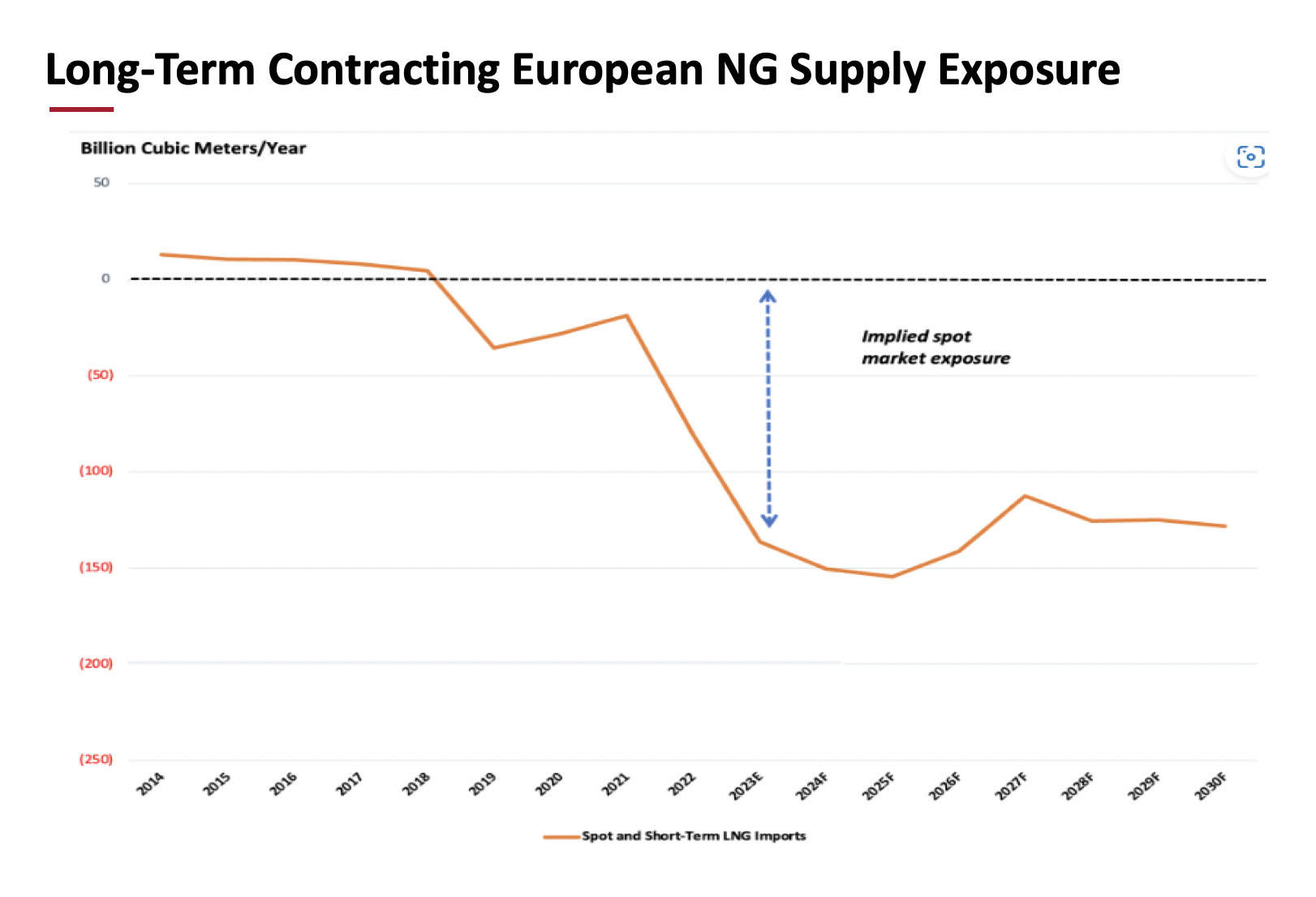

That would appear to be good news for U.S. LNG producers as far as market demand, but not necessarily for European customers. Russia’s share of the European gas market increased after the invasion from 7% to the 12%-14% range. If Putin cuts the supply again, or if labor strikes in Australia interrupt LNG supplies from that country, prices could spike dramatically, Kissler said.

That could happen even with greater volumes of U.S. LNG on the market. Beginning in 2024, European long-term LNG contracts will expire, Kissler said, and a cold winter in 2025 would force Europe into the spot market to purchase gas. This is a result of policy decisions.

“They have some contracted [LNG], but their contracts are blending away because in 2050, they’re supposed to go to the net-zero effect, right?” he said. “No carbon, no fossil fuels.”

That would put Europe in competition with Asia for cargo ships laden with LNG.

“Asia’s also a great big buyer of LNG, especially on the spot market,” Kissler said, “but the thing that Asia has in place that Europe doesn’t is they have a lot of the contracts, so they can get first dibs on a lot of it.”

Recommended Reading

Deepwater Roundup 2024: Offshore Australasia, Surrounding Areas

2024-04-09 - Projects in Australia and Asia are progressing in part two of Hart Energy's 2024 Deepwater Roundup. Deepwater projects in Vietnam and Australia look to yield high reserves, while a project offshore Malaysia looks to will be developed by an solar panel powered FPSO.

Sinopec Brings West Sichuan Gas Field Onstream

2024-03-14 - The 100 Bcm sour gas onshore field, West Sichuan Gas Field, is expected to produce 2 Bcm per year.

US Gas Rig Count Falls to Lowest Since January 2022

2024-03-22 - The combined oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, fell by five to 624 in the week to March 22.

NAPE: Chevron’s Chris Powers Talks Traditional Oil, Gas Role in CCUS

2024-02-12 - Policy, innovation and partnership are among the areas needed to help grow the emerging CCUS sector, a Chevron executive said.

BP: Gimi FLNG Vessel Arrival Marks GTA Project Milestone

2024-02-15 - The BP-operated Greater Tortue Ahmeyim project on the Mauritania and Senegal maritime border is expected to produce 2.3 million tonnes per annum during it’s initial phase.