Oil companies are aiming to further lower emissions amid a global push toward cleaner energy sources. (Source: Shutterstock.com)

A carbon tax will be required to accomplish the transition to cleaner forms of energy, according to panelists of oil industry executives speaking during a recent forum.

It will also require more than oil and gas companies making changes, they said.

“If you want society—and it’s not just the oil and gas space—to drive a big change, you need government and legislation to drive that change across all of the industries in a common way,” said Daniel Fitzgerald, COO of Norway-focused offshore player Lundin Energy.

Speaking on redefining the role of oil and gas in the global energy mix during a recent Reuters event, talk briefly turned to taxes levied on carbon amid the global push to lower emissions.

Norway, home to large offshore producing fields that include Johan Sverdrup and Edvard Grieg, has had a carbon tax in place since the early 1990s. The country plans to more than triple the tax on CO2 by 2030, raising the cost on emissions to about $237 per tonne from about $70 today for companies producing hydrocarbons on the Norwegian Continental Shelf, as it aims to chop its greenhouse gas emissions in half.

It has motivated oil and gas companies, with eyes on profits, to operate more efficiently.

“It drives things like the electrification of our assets. These things are profitable and they’re profitable because we’re removing CO2 emissions,” Fitzgerald said. “We’re getting higher uptime, higher efficiency, and we’re reducing our exposure to some of that tax.”

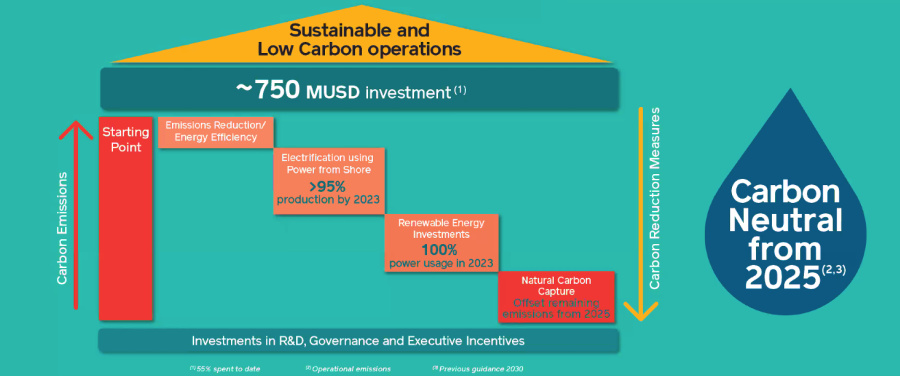

The Nordic E&P is among many oil and gas companies targeting carbon neutrality—in Lundin’s case by 2025—as investors, government authorities and other stakeholders demand change. While some companies are investing in renewable energy, others are shrinking their carbon footprints with carbon capture projects, eliminating routine flaring and electrification.

Twenty or so years ago, government subsidies helped wind and solar get off the ground, Fitzgerald said, noting those projects are now profitable without subsidies in parts of the world.

“For us, I think a carbon tax is the right way forward,” he said. “It drives society to behave in the way that we need to behave, and it drives innovation in exactly the space that we need it to.”

Christine Healy, vice president of Total SA’s Caspian and European E&P operations, had similar thoughts. She called a price on carbon part of the solution.

“It makes sense from a policy perspective that drives the behaviors and the change that we need to see. … When we don’t have a price on it, we don’t perceive to value it,” Healy said. “It’s important that we have some metrics. Different countries are going to get there on different schedules.”

That, she added, poses a challenge for companies like Total that invest in multiple countries. However, countries need to work on a timeframe that “makes the most sense for them but all of us, hopefully, with the goal of meeting the Paris Accord.”

While several energy companies like Lundin and Total have voiced support for a carbon tax, not everyone supports it.

RELATED: Occidental Petroleum Opposes Carbon Tax, Says CEO Vicki Hollub

Developing countries still need cheap energy.

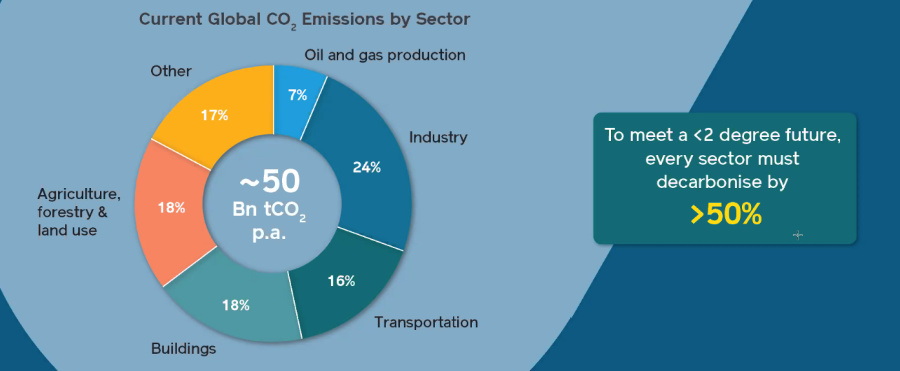

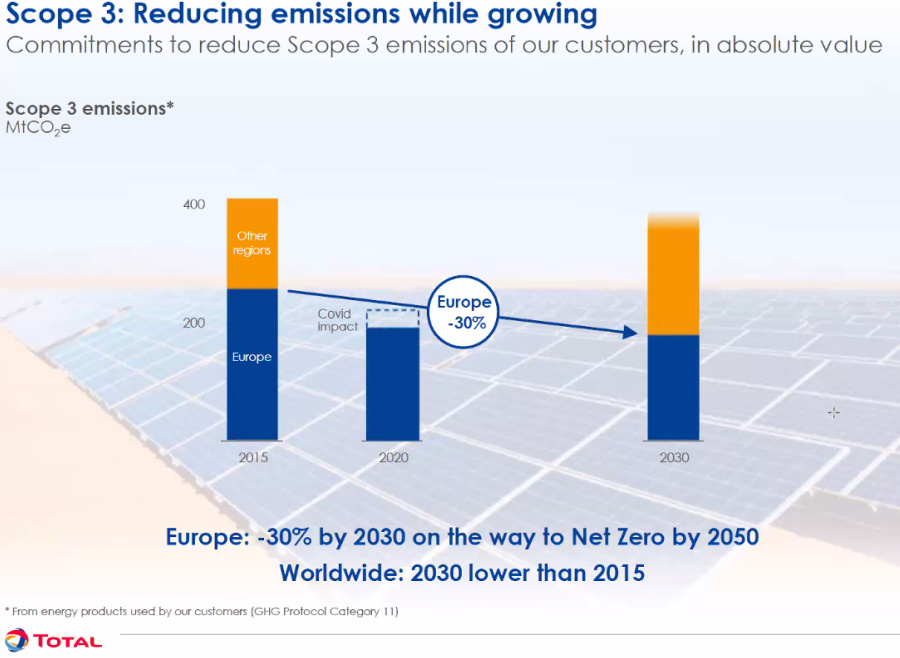

Healy called the carbon tax one of many tools or layers needed to solve the world’s emissions challenge. Another, both speakers agreed, seemed to be tackling what Fitzgerald described as the “elephant in the room for the oil and gas industry and the hardest challenge to face”—Scope 3 emissions.

As defined by the U.S. EPA, Scope 3 greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions result from activities from assets that the reporting company doesn’t own or control but indirectly impacts its value chain. Scope 2 emissions are indirect emissions from sources owned or controlled by the company, while Scope 1 emissions are direct emissions from sources owned or controlled by the company.

“Our Scope 3 is somebody else’s Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, and so we all need to do our part, whether it’s the upstream sector, whether it’s transport, whether it’s industry, whether it’s agriculture,” he said. “We all have to do our part to deal with our own Scope 1 and Scope 2.”

Lundin’s path to carbon neutrality includes investments in emissions reduction/energy efficiency, electrification using power from shore, renewable energy and carbon capture. The company is also pushing its supply chain customers to deal with their Scope 1 and 2 emissions, he said.

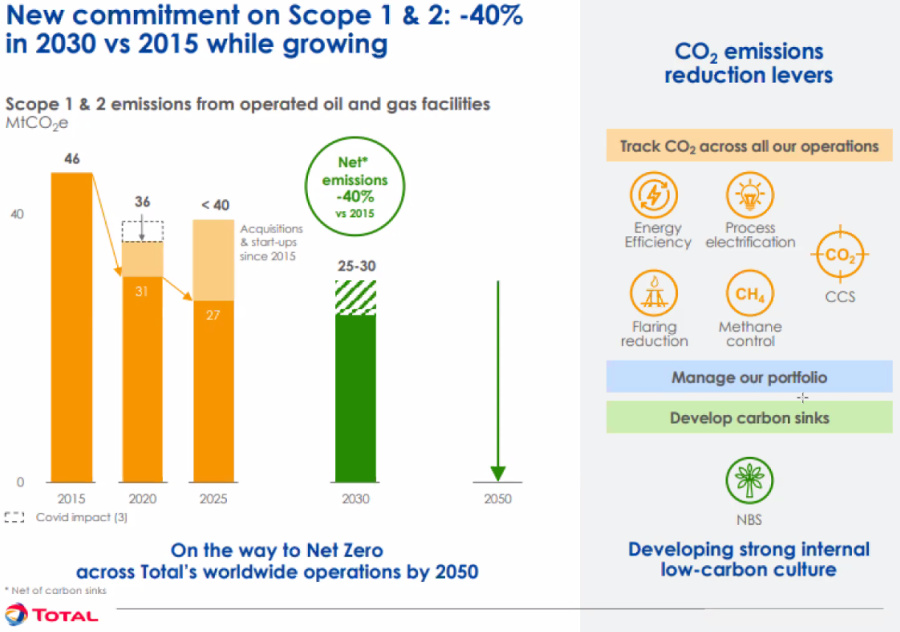

Pledging carbon neutrality by 2050, Total is also working to reduce its Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions while growing energy production to meet the world’s energy needs. Natural gas and oil will remain a significant part of the company’s portfolio through 2030, but it is also adding biofuels, electricity, wind, solar and carbon capture investments.

“At the same time, we’re committing to reduce our emissions,” Healy said, by tracking CO2 across operations as well as focusing on energy efficiency, flaring reduction and methane control. “We also see that there’s a necessity for carbon sinks—two kinds of carbon sinks, nature-based solutions where we’re investing a $100 million a year right now and carbon capture and storage.”

Attention is also on developments with lower carbon footprints, considering the executives believe portfolio is key to each company’s approach to lowering emissions.

“Where we have new assets, where we have power from shore solutions, we will marry that up with a renewable option,” Fitzgerald said, “which means we’re doing it at zero carbon. Where we have residual emissions, we will ensure we have either tree planting or similar nature-based solutions at the same time.”

There is no one solution to the world’s emissions problem, panelists agreed.

“I think fundamentally companies that have established that they are, first of all, taking the problem seriously and have a credible plan for dealing with the problem, they’re going to be further ahead than those who don’t,” Healy said.

Recommended Reading

TC Energy's Keystone Oil Pipeline Offline Due to Operational Issues, Sources Say

2024-03-07 - TC Energy's Keystone oil pipeline is offline due to operational issues, cutting off a major conduit of Canadian oil to the U.S.

Pembina Pipeline Enters Ethane-Supply Agreement, Slow Walks LNG Project

2024-02-26 - Canadian midstream company Pembina Pipeline also said it would hold off on new LNG terminal decision in a fourth quarter earnings call.

TC Energy’s Keystone Back Online After Temporary Service Halt

2024-03-10 - As Canada’s pipeline network runs full, producers are anxious for the Trans Mountain Expansion to come online.

Enbridge Announces $500MM Investment in Gulf Coast Facilities

2024-03-06 - Enbridge’s 2024 budget will go primarily towards crude export and storage, advancing plans that see continued growth in power generated by natural gas.

Enterprise Gains Deepwater Port License for SPOT Offshore Texas

2024-04-09 - Enterprise Products Partners’ Sea Port Oil Terminal is located approximately 30 nautical miles off Brazoria County, Texas, in 115 ft of water and is capable of loading 2 MMbbl/d of crude oil.