(Source: Shutterstock.com)

[Editor's note: This story appeared in the June 2020 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here. It was originally published May 29, 2020.]

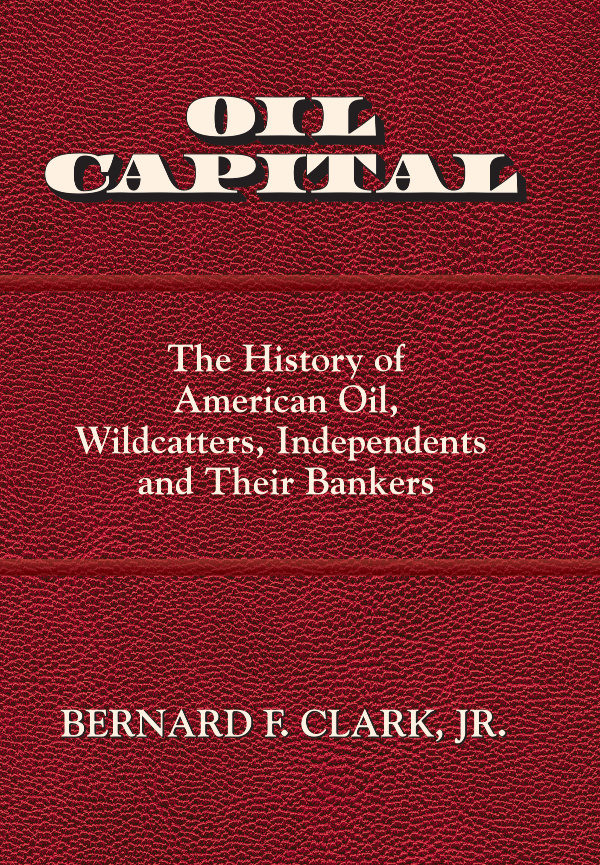

Book chapters are numbered. In Buddy Clark’s book—a history of oil and gas finance that kicks off with how mineral ownership was handled in the Iron Age—were the 1980s going to end up falling under Chapter 7?

Would 2015 fall to Chapter 11?

Without artifice, it happened that the former landed under Chapter 6; the latter, Chapter 10.

That left Chapter 11 available for the next oil and gas event. And here’s 2020. Oil and Gas Investor visited with Clark, a nearly 40-year energy finance attorney with Haynes and Boone LLP, in late April for his thoughts on the current state of capital flow or gridlock.

If he were to add a chapter to “Oil Capital: The History of American Oil, Wildcatters, Independents and Their Bankers” (2016) one day, would 2020 be worthy? It would, he said.

The 1980s downturn and 2015 were geopolitical and supply-driven. “You still took the oil out of the ground, it went to the refinery and people were buying it. The problem now is that you don’t have people at the other end buying it,” he said.

Among recent events, Reuters reported—citing three confidential sources—that a few of the major oil and gas lenders were working to create “companies to own oil and gas assets” and “to hire executives with relevant expertise to manage them.”

Spoiler alert: Clark said that isn’t likely. Banks have usually been reluctant to “take the keys” to oil and gas assets. And they still are, he said. Operating them isn’t a bank’s expertise, and the risks don’t really fit within the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.-regulated realm.

Meanwhile, an E&P drew $90 million—the remaining capacity—under its revolver one Thursday. In some credit agreements, that’s called hoarding.

That evening, the syndicate wrote that it had decided to reduce the borrowing base to $175 million, effective the next day. That’s called “using the wild card.”

The E&P would need to return $75 million. Cash on hand, including the $90 million drawn, was about $110 million. Its derivatives had a mark-to-market value of about $47.4 million.

Clark’s take on 2020 includes an examination of “the least desirable of all bad options.”

Investor: Without knowing right now where 2020 is going, will some banks take the keys to oil and gas assets after all?

Clark: It would be the exception and not the rule—because it would be so complicated, especially with syndicate banks taking over operation. They wouldn’t enter it lightly, but it is an option they have.

I have asked other bankers about the Reuters article and they said, ‘No, we’re not doing that.’ It is possible that whoever planted that story is trying to generate business for themselves. I’ve gotten a lot of calls from people saying, “We’re really good contract operators. If you know of anything, keep us in mind.”

Bankers generally don’t call me for recommendations on contract operators, but the number of unsolicited emails shows you there is a lot of appetite for it on the contract-operating side.

I just don’t know what appetite there is on the lender side.

Investor: A syndicate bank would have to get the other, say, 11 banks to agree to join the takeover, or it would have to buy the other banks out.

Clark: Yes. And, if they do, at what price? Do the others hold out for 100 cents on the dollar even though the loan is probably at some discount?

Even getting it up and running seems problematic. And once you bought it, you own it. They could be owning it for a while. Who knows when the market is going to turn around?

Investor: Banks absolutely won’t take over the assets then?

Clark: It would be the last option they would want to choose. But even before that—even if they didn’t like the management team or had lost confidence in them—they would try to keep the management or bring in new management and just keep their liens in place.

Banks aren’t looking to take inventory in, wait for the market to turn around and make a killing. That’s not their business. Once the loan is in default, they are just looking to recover as much as they can of their principal outstanding.

It is not like a private-equity shop that will put a couple of broken portfolio companies together and just wait this out. It’s a different mentality for banks.

But I have heard the concept that banks may find private equity willing to put a little money in a deal, take over the equity and, if banks are the first out, they may give that company or those assets a little longer rope.

That way the banks aren’t speculating in the oil and gas market, which they’re prohibited from doing. But they are maybe keeping the operation going a little longer and waiting for the market to turn around.

That seems more plausible to me than a bank taking direct ownership.

Investor: In the 1980s, there were concerns among banks about assuming environmental risks if taking the keys to oil and gas properties. It’s been mostly resolved but not completely resolved?

Clark: Well, it depends. If it’s with a foreclosure, there is a provision in Superfund [the federal Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act of 1980] that gives creditors an exception to the liability for preexisting conditions. That can only last for so long, though.

In the 1970s and early ’80s, environmental risks were much more of an unknown and therefore more important to banks. These days, banks have become pretty comfortable with the environmental exposure.

There’s really no way to avoid the potential of being sued by somebody under some kind of law—even a nuisance law. But the risk has become more acceptable to all parties in the industry.

I don’t think environmental risks stop the banks as much as just the sheer magnitude of operating.

Investor: What’s that math look like?

Clark: We’re not talking about one lease and one well and one bank. We’re talking about potentially hundreds of leases and thousands of wells and multiple banks in the syndicate with varied agendas and ownership percentages. A lot of the wells right now may be uneconomic and need to be shut in, plugged and abandoned.

And think about the outlay. You’re asking your bank’s board of directors, “We need another couple of million to plug these wells that we’re never going to get back.” Think about trying to sell that: “Give me some more money to put in a hole that you’ll never see again.”

I don’t think there is any banker out there that would want to make that ask to its credit committee or board of directors. That’s why I see that concept as being the least desirable of all bad options.

Investor: What happens to the operators receiving “going concern” statements from auditors?

Clark: That breaches the financial reporting standards under almost every RBL [reserve-based loan]. Those guys may theoretically be right side up today, but the “going concern” says that within the next year they may get upside down.

Such a default gives the banks the right to commence remedies and take over, but I really can’t imagine why they would want to. That would force a company into bankruptcy.

Why would a bank or bank group want to put out a company that is currently operating and isn’t wasting money? They’re basically working for free because they’re not going to get any equity out of it.

Why would you ever foreclose on a company like that? If the banks take that action, they’re totally stuck. The operator likely would run to the bankruptcy court. Then they’re in a free-fall bankruptcy without an exit plan, and that’s a mess.

Foreclosure typically could take up to 90 days once the decision is made to start the process. There’s plenty of time to do the work involved to file for bankruptcy. So unless people are walking away from their assets, I don’t see a foreclosure ever getting to the red-letter date where you sell the properties at the courthouse steps. A lot of things could happen between now and then.

Investor: After the spring of 2016, when your book was published, not much changed. Is 2020 worthy if you added a chapter now?

Clark: Yes, I really do think this is. The magnitude of what’s going on right now is bigger than what happened in the 1980s. The demand loss is what has hammered things. In the ’80s and again in 2014 and maybe in 1999, OPEC tried to flex its muscle to regain market share.

While it was bad news for U.S. producers, the energy markets continued to function. You still took the oil out of the ground, it went to the refinery and people were buying it.

The problem now is that you don’t have people at the other end buying it. This one is fundamentally different.

Demand has to come back, but it’s going to be a while before it does. And it won’t be switching a light on where it just comes back overnight.

Investor: Will the way banks underwrite loans against oil and gas properties change in some way—and permanently?

Clark: They’re already trying to tighten it up right now, but we saw that in the 2009 to 2010 cycle, and within months they started relaxing them again. The pricing is getting a little higher right now, and covenants are getting a little tighter. Anti-hoarding provisions were introduced in 2015 and disappeared in 2017. Those are coming back. But the structure stayed the same: secured loans with a semiannual borrowing base redetermination. I think that stays.

Investor: What again was the anti-hoarding provision?

Clark: It’s when companies look like they are about to enter into bankruptcy and draw down their facilities to the maximum borrowing base. The borrowers call it a “defensive draw”; the bankers see it differently.

The bank usually has that day to fund a draw request, so there is usually very little time to get together with their lawyers [to decide] if they have to fund it and what kind of restriction they could put on it. The banks ended up funding them.

There were at least a handful of instances where both sides—the banks and the operators—put their guns down and worked through a period of forbearance and restructure, which is always better—both sides doing it in a more rational fashion.

But the defensive draws gave rise to the anti-hoarding provisions. Yet managing that was difficult. The anti-hoarding provisions restrict the daily maximum amount of cash that a borrower can keep on hand; anything above the maximum is swept that night to pay down the loan.

Operators could only have so much cash on hand, but they get paid once a month on their production; meanwhile, they have payroll all month long. The banks finally kind of dropped it in 2017.

Today, as banks get more nervous, we’re seeing it, and we’re seeing borrowers push back again like they did before.

Investor: What’s something tried in the past that no one should even think about trying today?

Clark: When you have two broken companies, call it “a merger of equals” and think you will make it a healthy company, it has always been a mistake to put these two companies together.

The only thing it does is reduce the G&A [general and administrative costs]. But if the properties are bad, you don’t improve them underground by just merging two companies.

Another lesson was in the 1980s when the energy banks were being punished because the stock market didn’t like oil and gas anymore, so they doubled down on real estate lending. I would say, “Don’t get out of this just because you think there is a better place to make investments. That’s not necessarily guaranteed.”

You can look at what happened to all of our Texas banks in the ’80s. Maybe the watchword is “Don’t chase bubbles.”

Investor: Technology?

Clark: That’s hot.

Investor: A lot of technology remains unbankable, though.

Clark: Right.

Investor: The bankers—the individuals themselves—how are they doing?

Clark: I think they are soldiering through. A lot of people in the industry see it as their job to minimize the damage and prepare for when the markets do turn around. At least the bankers have an option to move from one area of the bank to another.

These oil and gas guys would have to find a new industry to get into. That’s a tougher road.

There will be half as many people in the industry. It’s a fundamental change. And I don’t know if it will recover fully. I have concerns that we are facing a new normal.

Investor: Any banks quitting oil and gas?

Clark: Some European banks have said they aren’t going to make any energy loans.

This happened in the 1980s too. If you want to talk about mistakes, a lot of foreign banks got out of the business of making loans to U.S. producers and then they would come back.

BNP Paribas is an example—in and out, in and out, and they’re out again. I don’t know if they will ever come back. I think the French banks have a political bias against hydrocarbons.

Also some U.S. banks that have been late entrants, now their investors are saying, “Why did we ever get in this business?”

Banks that might be deemphasizing RBLs might be the foreign banks first [and] then the small regional banks, particularly outside the Gulf Coast region.

It would take something for the medium-sized banks and certainly for the bulge-bracket-sized banks—I hope—because the industry needs that capital to survive.

WTI has to be above $40 for the banks to be comfortable with making loans.

Investor: Will it be a generation before the generalist investors forget, like they forgot the 1980s?

Clark: If you measure generations in terms of months, yes. In 2015 there was [the attitude], “This is the worst ever, and we will never recover.” Then in 2016 they issued all the junk bonds again. In 2017 WTI was $65, and it was great. It got rid of the anti-hoarding provisions.

I don’t think it takes a generation at all. This will probably last longer, but it’s probably not a 30-year event.

The market sentiment is measured by the prices for hydrocarbons. Once those start going up to a level that is worth investing in, everyone’s going to jump in, invest and think “It’s different this time” and “We’re a lot smarter” and protect themselves against all the bad things that happened.

But—I don’t know who said it—you always prepare for the last war and not the current war. So who knows what’s ultimately going to happen?

But I don’t think people will stay away from the industry unless Elon Musk invents a new source of energy that can be stored as easily and has as much energy density as hydrocarbons. Until that happens, you’re still going to see investment in oil and gas.

Investor: Do RBLs still have provisions for if the Texas Railroad Commission imposes prorationing?

Clark: Yes. There are some vestiges in oil and gas loan agreements from the ’70s that nobody took out, so they’re still there. In my entire career, I always said, “We ought to strike that because they will never happen again.”

And I don’t think it will happen again because the market is self-correcting and the Texas RRC doesn’t have the market power to change oil prices even if it wanted to. So those are two strikes against it reimposing prorationing. [Editor’s Note: On May 5, the Texas Railroad Commission dismissed the prorationing motion put forth by some Texas producers.]

Investor: Every cycle seems to bring more provisions to RBLs. Will more be added? Or is this just covered by “force majeure” or “pandemic”?

Clark: You really don’t have force majeure in a credit agreement. The borrowers’ obligation is to repay money. Under a credit agreement, this pandemic will not excuse the obligation to repay the loan.

“There will be half as many people in the industry. It’s a fundamental change.”

I do think you’ll see other provisions being included in credit agreements—not the least, anti-hoarding provisions.

You may also see banks wanting to have the ability to pull the wild card instantaneously. A lot of bankers are asking us, “What are our notice requirements? How long do we have to wait?”

And a lot of times, the procedures are old-fashioned because they contemplate the borrower asking for a wild card to increase their borrowing base. Well, these banks are saying they don’t want to wait for the spring redetermination.

If they can reduce the borrowing base down to current loans outstanding, then there’s no availability, and the borrower doesn’t have the availability to make a defensive draw.

If the banks call a wild card, under most agreements they have to wait even 24 hours. If the borrower is going to pull a defensive draw, they will do it in that 24-hour period.

For the banks’ protection, they want to be able to do it instantaneously and just notify the borrower that “Your new borrowing base is your current outstanding, so don’t ask for more money.”

I think you’ll see banks trying to impose protections like that.

There are some already out there where the bank can just come up with a new borrowing base. They don’t have to tell the borrower they’re even talking about it; they notify the borrower, and that’s it.

Investor: What else should we know?

Clark: It’s the last week of April right now. By June 1 when this is published, everything we’re talking about could be incredibly stale and 100% wrong.

I don’t think anyone truly knows if today is now the reset and this is the new normal going forward.

It’s such a dynamic industry that you just have to constantly be on your feet. And anybody—i.e., me—could easily say the opposite next week, depending on what occurs in the interim.

It’s really difficult to make any prognostications, and it may be difficult to make any reflections on what’s happening.

It’s hard to have perfect knowledge until a number of years after an event.

I’m not writing any new chapters anytime soon. It will all have to percolate through the system first.

Investor: We’re looking forward to 2024—whatever it takes to get out of 2020.

Clark: Yes. You would have a lot of company at that party.

Hopefully, everybody can get together again then too.

Recommended Reading

Defeating the ‘Four Horsemen’ of Flow Assurance

2024-04-18 - Service companies combine processes and techniques to mitigate the impact of paraffin, asphaltenes, hydrates and scale on production—and keep the cash flowing.

Tech Trends: AI Increasing Data Center Demand for Energy

2024-04-16 - In this month’s Tech Trends, new technologies equipped with artificial intelligence take the forefront, as they assist with safety and seismic fault detection. Also, independent contractor Stena Drilling begins upgrades for their Evolution drillship.

AVEVA: Immersive Tech, Augmented Reality and What’s New in the Cloud

2024-04-15 - Rob McGreevy, AVEVA’s chief product officer, talks about technology advancements that give employees on the job training without any of the risks.

Lift-off: How AI is Boosting Field and Employee Productivity

2024-04-12 - From data extraction to well optimization, the oil and gas industry embraces AI.

AI Poised to Break Out of its Oilfield Niche

2024-04-11 - At the AI in Oil & Gas Conference in Houston, experts talked up the benefits artificial intelligence can provide to the downstream, midstream and upstream sectors, while assuring the audience humans will still run the show.