“Port Arthur LNG will benefit from intrastate pipelines out of the Permian Basin,” said Bill Bullock, executive vice president and

Independent producers seem to have a similar sentiment. UpCurve Energy, a portfolio producer of Post Oak Capital, operates in the Delaware Basin. “We have

UpCurve works with the larger midstream operators

He also noted that differentials indicate the market expects tightness to continue in the near term. “There is a lot of progress on new capacity,”

In both the Delaware and Haynesville, “gas has been crushed,” said Frost W. Cochran, managing director at Post Oak Capital. “There has been significant cash price degradation in the Delaware Basin but oil production is still driving activity.” Post Oak is primarily upstream, but also has some midstream operations, which gives Cochran and his colleagues good insight into both sectors.

The tightest infrastructure capacity for the major U

He also noted that midstream operators seem to be adding gathering and processing just as new wells are being brought into production. “That is mostly because of their own supply-chain issues with equipment and construction, but it means that the timing is

The oil side is “no big deal,” in terms of transportation,

Enough LNG tankers?

The numbers support the assertions that midstream investment is taking place. East Daley forecasts capex and EBITDA for 22 of the largest midstream companies. East Daley expects the group to spend $25.6 billion in capex in 2023, decreasing to $20.6 billion in 2024. Enbridge and TransCanada are the top

Midstream companies have been busy building “a runway of new pipe through 2025,”

“The due diligence for an LNG project is based on global demand

He also noted two other infrastructure elements that bear watching. The order book for new LNG tankers is full, so there could be some short-term disruptions in actual loading and sailing if there are not sufficient vessels at any time.

That variable, along with spikes and dips in demand driven by heat waves or severe storms, mean that storage will matter more than ever. “Storage capacity becomes very important in volatile markets,” Smith said. “Midstream is clued in to this already, and some large operators have been investing in buying storage capacity.” As far back as 2021

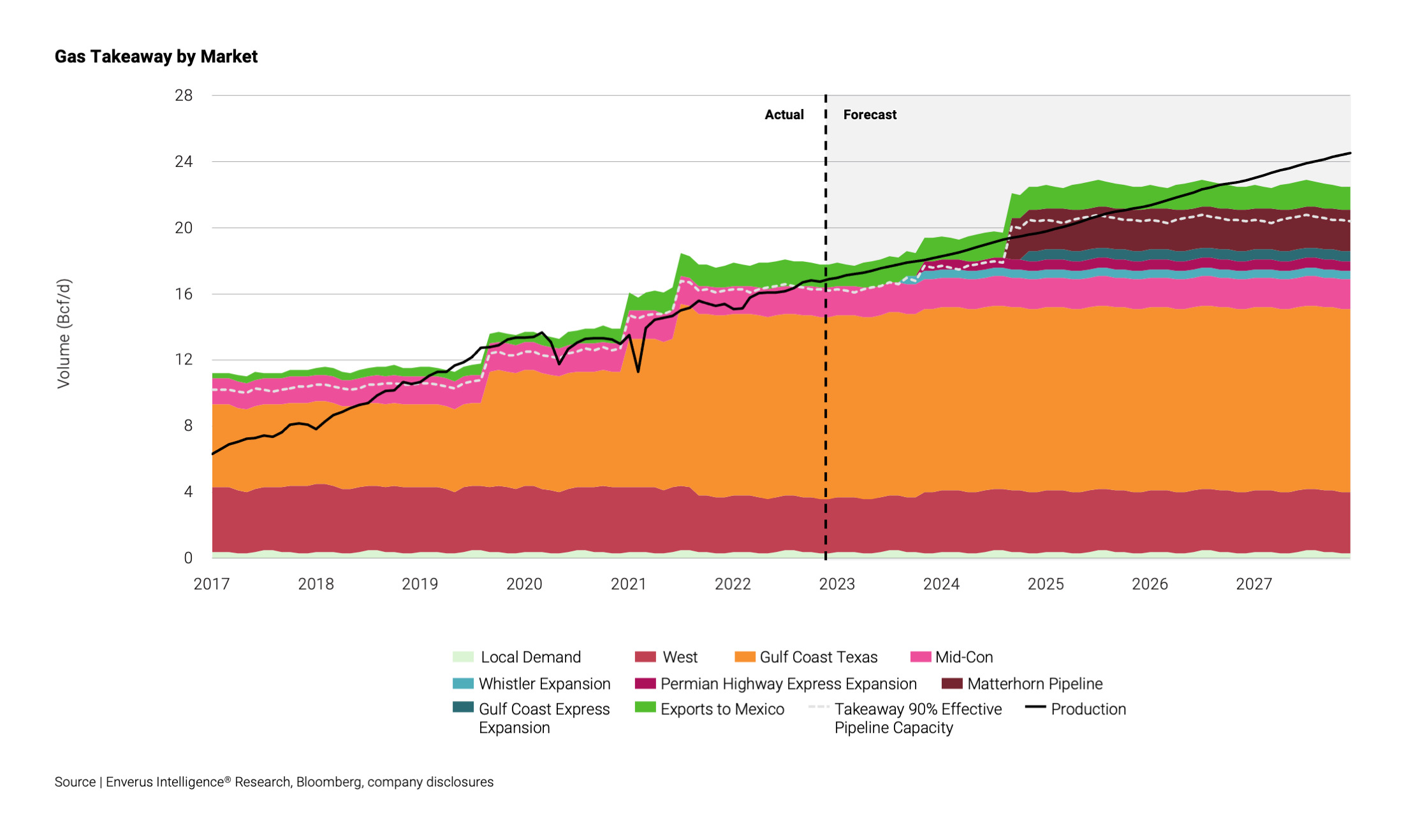

“The big area of focus has been gas takeaway from the Permian,” said Hinds Howard, portfolio manager at CBRE Investment Management. Noting that there have been both expansions and greenfield development, he added, “capacity is not the current constraint there,” but there are some pinches starting to show in other basins.

“The Haynesville has a lot of projects under development,” Howard explained. “Overall, it’s about 85% full, but going south is a constraint, which is actually where the gas wants to go. The major players, the ones with the big footprints already, are the ones adding capacity.”

Bakken gas takeaway is also constrained. “Producers are recovering more ethane to free capacity,” Howard said. “As we approach BTU limits we may need more of that.” Next steps would include reconfiguring existing infrastructure. For example, TC Energy is considering options for the Bison Pipeline that connects the Powder River Basin in Wyoming to the Northern Border system in North Dakota.

The Appalachian has long been the most constrained basin, and that is expected to remain the case. “Existing infrastructure is at about 90% of capacity. Most expectations are for that to hold steady on, with normal incremental increases

Equitrans is sticking to its projection of having the $6.6-billion Mountain Valley Pipeline development completed by the end of the year, and though greenlit in early June by Congress, the embattled project, the embattled project still has remaining permitting and litigation hurdles..

Macroeconomic shift

In all the examination of specific basins and individual projects, it is important to bear in mind the broader context, noted Kate Hardin, executive director of Deloitte’s Research Center for Energy and Industrials. “We are seeing gas production at more than 100 Bcf/d. That is significant production in response to real demand,

That is a major success story, but a very recent one. “If you look at infrastructure in the Permian, we are at about 90% utilization for gas but only about 70% for oil,” said Hardin. “Looking ahead to 2026, gas takeaway is expected to be at 80

Permian production is still strong, Hardin acknowledged, “but as decline rates set in, the gas-to-oil ratio will shift. At the same time, the market for gas is changing. And producers are starting to understand that. There is more attention to gas than ever before. In 2022

The macroe

Transportation capacity is more complex than just solving for the production volumes out of a basin, said Baran Tekkora

Tekkora made a point to dispel a common

That, in turn, “created a pinch coming out of the pandemic, which caused the pricing spread between high-production basins and the market to widen significantly,”

‘Catch-up mode’

Broadly speaking, “the industry has been able to maintain capital discipline through volatile prices in the last few years, primarily due to investors rewarding such capital discipline, but also other factors including supply-chain issues and dearth of available skilled labor,” said Amol Joshi, vice president and senior credit officer at Moody’s Investors Service. “All that has kept a lid on production growth as well as [has] available oilfield-services capacity.”

So

“We see the need for a massive amount of transmission pipeline infrastructure to be built out in the Haynesville and Permian to support the next wave of LNG projects coming online in the second half of the decade,” said Jon Snyder, vice president of intelligence at Enverus. “For the Haynesville

The slowdown in Permian development in 2020 did help provide some relief to the basin, “but as production has recovered, the basin has started to bump up against available takeaway,” Snyder

The fundamental challenge in the midstream is that the economics always favor bigger pipes and compressors,

As big as pipes can get, LNG trains are even more chunky in terms of capacity. Each standard liquefaction terminal of 4.2 million metric tons/day needs about 600

“That is a lot of demand coming on in a relatively short time,” said Dell. “There is about 25 million tons a year on LNG coming on in the next few years just in Texas. Across the industry

Infrastructure for crude has plenty of capacity relative to production with the possible exception of long-haul pipeline to Corpus Christi,

“The oil side is a bit easier,” said Ellis. “It’s oversupplied with transportation. Some pipes are going from

On the gas side

Looking south, Ellis noted significant improvements in gas exports to Mexico. “There has been good progress in Mexico. TC Energy came to some agreements with Mexican utilities on financial terms. The permitting and the infrastructure on this side of the border are mostly in place. What is needed now is for the Mexican midstream to connect. ONEOK is also planning Mexican pipelines. There is definitely a lot of progress

Balance is always temporary, reiterated Riverstone’s Tekkora. “I believe the next imbalance or bottleneck is likely to occur in natural gas liquids fractionation and infrastructure. The sector was arguably overbuilt in 2019 and 2020, but the industry has done a good job of filling that same capacity. I believe there’s likely to be some tightness in 2024 and 2025 ahead of new infrastructure and fractionation capacity coming available.”

Processors will have some flexibility in NGL production if the tightness comes sooner by switching to ethane rejection mode,

Recommended Reading

Up to 50 Firms Seek US Oil Licenses in Venezuela, Official Says

2024-05-23 - Washington aims to prioritize issuing licenses to companies with existing oil output and assets over those seeking to enter the sanctioned OPEC nation for the first time, sources told Reuters.

Exxon Mobil Keeps Its Options Open in Guyana and Globally

2024-05-23 - Exxon Mobil Guyana Ltd.’s President Alistair Routledge said the company is seeking resources offshore Guyana that compete financially within its portfolio.

Weatherford to Deliver Drilling Services to Bapco Upstream in Bahrain

2024-06-06 - The contract with Bapco Energy subsidiary Bapco Upstream replaces Weatherford’s old drilling services contract from 2015.

Third Suriname Find for Petronas, Exxon Could Support 100,000 bbl/d FPSO

2024-05-17 - A recent find offshore Suriname in Block 52 by Petronas and Exxon Mobil could support a 100,000 bbl/d FPSO development, according to Wood Mackenzie.

Mexico’s Zama Drama Eases, but Not Over for Talos, Other IOCs

2024-06-26 - Houston-based Talos Energy and its Block 7 consortium partners could make FID on the Zama field development sometime in the next year. But despite the importance placed on the project to secure energy security for Mexico, the consortium continues to run into headwinds.