The Permian Basin is one of the leading battle-fronts in the war against the production-decline curve. Deeper exploration for Devonian gas targets is going on, but in this region, smart field management, cost-conscious waterfloods and CO2 floods are gaining increased importance. For the five years ending in 2001, 33% of growth in onshore Lower 48 proved oil reserves and 9% of the growth in gas reserves took place in this basin, according to the Department of Energy and the U.S. Geological Society (USGS). "What we see here is that the risk is not dry-hole risk, it is economic risk," says one observer who nevertheless has started his own company. "You can maybe make enough production to get your money back, but not enough to make money beyond that." Common solutions in this region may not be new, but applying them with attention to every detail reduces costs and enhances recovery. The newest reservoir modeling software packages are key. High oil prices help economics, of course, but it is sterling execution that often makes the real difference. One example is the Cogdell Unit operated by Oxy Permian. Another is the Dollarhide Unit in Andrews County north of Midland, now under the watchful eye of Pure Resources, a unit of Unocal. Finally, Parallel Petroleum has several old fields in the basin in which it has been increasing production. Cogdell Unit Since its discovery by small independents in 1949, what is now known as the Cogdell Unit has produced 280 million barrels of oil and 226 billion cubic feet of gas. The gross pay zone in Pennsylvanian Canyon Reef is 500 to 700 feet thick and the permeability is six millidarcies-precisely the kind of characteristics that have allowed the Permian Basin to dominate U.S. production for many years. The unit resides in a high-toned neighborhood straddling the Kent and Scurry counties' line about two hours northeast of Midland. ExxonMobil's huge Salt Creek Unit to the north is under CO2 flood. Kinder Morgan's Sacroc Unit, also under CO2 flood, lies to the south. Sacroc is estimated to have 1.25 billion barrels of oil in place and a 50% recovery factor. Like most fields of this vintage, Cogdell has changed hands many times. It was unitized as the Cogdell Canyon Reef Unit in 1955 with Texaco as the operator. The latter was still operating when production peaked in 1970-about the same time U.S. oil production peaked. In 1993, Apache Corp. bought Cogdell, but in 1998 it sold it to Altura, a new company owned by Amoco (now BP) and Shell. The current operator, Occidental Petroleum, took over when it bought Altura in April 2000. Oxy Permian now contributes about 44% of the parent company's total production and has an estimated 1 billion barrels of proved reserves. At one time Oxy Permian was running as many as 90 well-servicing rigs in the Permian daily. Cogdell was under waterflood when Oxy took over, making 98% water and 2% oil. At the same time, some 300 wells were either temporarily or permanently plugged and abandoned, so it was ripe for rejuvenation. To minimize project risk in this complex reservoir, Oxy Permian broke the project into phases, with the north dome area going under CO2 flood in 2001 and the south dome area under CO2 flood in 2003. This year the company is taking a break from large capital outlays to study another part of the unit that is not being CO2-flooded yet, according to Matthew Hyde, asset manager for Oxy Permian in Midland. "We are currently doing the technical evaluation, including reservoir modeling, to support another phase at an area we call South Middle Dome. We are looking towards implementation in 2005," Hyde says. The company has full 3-D seismic coverage over the unit. It will integrate seismic, log and other data with historical production data to predict future outcomes. "The challenge is conformance, or making sure the CO2 or water we inject goes where we want it to go. We are still digesting conformance data from the first two phases, monitoring oil-, CO2- and water-flow streams. We've done a full reservoir model that incorporate all these fluids." Each reservoir responds to CO2 injection differently. This particular one-Pennsylvanian Canyon Reef-responds rapidly, so Oxy Permian gets oil within the first year it starts injecting CO2. "It's a plus in that you get oil sooner, but on the other hand, you have to have the infrastructure in place sooner to handle the produced CO2-to process and reinject it." The produced CO2 and hydrocarbon gas go to Kinder Morgan's nearby Sacroc facility to knock out the natural gas liquids (NGL) and are then sent back to Oxy Permian for reinjection. Both companies share in the NGL revenues. The market price for delivered CO2 is 60 to 70 cents per thousand cubic feet. "We are constantly balancing what we need to purchase to inject, with what we are producing and can reinject," Hyde says. The front-loaded cash costs are $16 per barrel, but those decline to $12 or $13 per barrel as the old oil field responds with more production. The crude is good quality, with a gravity of 41 or 42 degrees, so it commands a premium. Most of the company's CO2 floods are in shallower Permian San Andres zones. This deeper Pennsylvanian section is costlier and more difficult to predict. However, knowing the area is bracketed by the prolific Salt Creek and Sacroc units gave the company encouragement. "This just requires a high level of technical review and scrutiny," Hyde says. Unit output has grown from 1,300 barrels per day to 5,800 per day. The company estimates the field's useful life has been extended by between 15 and 20 years. Dollarhide The Dollarhide Field incorporates multiple pays and four units north of Midland, all operated by Pure Resources, which is now a subsidiary of Unocal. It produces from Clearfork at 6,500 feet, Devonian at 7,500 feet, Silurian at 8,000 feet and Ellenburger at 10,000 feet. The field was discovered in 1945 by the old Magnolia and Humble Oil companies (which eventually became Mobil and Exxon, respectively). Production peaked in 1950 at 20,000 barrels of oil equivalent (BOE) per day. Unitization occurred in 1959. After Unocal became the operator of the Dollarhide units and initiated two waterfloods in the 1960s, production peaked again in 1969 at 19,000 barrels of oil per day. In 1985, a CO2 flood was started in the Devonian section, one of the earliest C02 floods in this basin. Pure became the operator in May 2000 when it merged with Titan Resources. Under new management, Pure increased the technical and capital resources devoted to the field and that has continued. "This is a success story using an integrated, multidisciplinary approach between geology, engineering and production operations," says Gary Dupriest, Permian Basin oil asset manager for Unocal. "When we increased the focus, we went out to the field every month to meet with our pumpers and foremen and discuss ideas for how we could increase the production and profitability of Dollarhide." The company also undertook a more detailed geologic and reservoir study that involved integrating maps, production histories, well logs, bottomhole-pressure survey data, porosity checks and recovery patterns. It reexamined existing 3-D seismic data to better understand how the faults were laid out through the field. "We discovered there were some underperforming areas and it became obvious that the recommendations the team was making would work," Dupriest says. The most important task was to improve the CO2 flood performance in the Devonian. That came down to understanding the horizontal and vertical conformance between the producing and injection wells in the Devonian reservoir. Study results showed that some of the injection wells were not injecting in the right place. It turns out that the Lower Devonian had 80% of the oil in place, but the bulk of the CO2 was going into the Upper Devonian that contained only 20% of the oil. "We also discovered that the current reservoir pressure in the Devonian was higher than the original reservoir pressure-in other words, we were injecting more CO2 than we were getting out, so we instituted a workover program." Pure worked over 60 producers and 25 injectors, including drilling sidetrack wells to make sure the producers and injectors were not separated by a fault. The producers were fracture-stimulated. On average the company saw increased daily production of 40 barrels per well. Meanwhile, the team also learned that in the Silurian zone, only about 23% of the 177 million barrels of oil in place had been recovered, a low recovery factor for a water-drive reservoir. "We ran some modern behind-pipe, cased-hole logs and found there were multiple zones that were originally thought to be wet, that were not wet. Some were deeper, some shallower. We did 20 Silurian workovers and increased that production by an average 60 barrels per day per well," Dupriest says. Pure's costs ranged from $20,000 to $200,000 per well. It is still meeting regularly to see what else-more workovers or expansion of the CO2 flood into other horizons-can be done. The net results? "We not only offset the decline, we increased production and reduced downtime. And, we were able to add reserves at less than $2 per barrel," Dupriest says. At the time Pure began operating Dollarhide in 2000, there were 233 producing and 141 injection wells. Production was about 6,500 BOE per day. Today production is up about 25% to 8,000 BOE per day. "The biggest challenge is the aging infrastructure. A lot of these wells were drilled in the 1950s, so there is collapsed pipe, parted casing. We make sure the wells have enough integrity to be worked on safely," says Dupriest. Diamond M Canyon Parallel Petroleum Corp. is fortunate as a small public company to have several Permian rejuvenation projects in place, two of which happen to occupy the same surface acreage in the Diamond M Canyon and Diamond M Clearfork fields of Scurry County, Texas. Diamond M Canyon Unit is a work-to-earn joint venture with Southwestern Energy. Parallel operates with 75% interest and supplies all the human and development capital. Southwestern contributed the asset to the venture. "This gave us an opportunity to get a very nice asset that was not for sale, and Southwestern gets its reserves developed at zero cost," says Don Tiffin, Parallel chief operating officer. The unit is located between the Sacroc Unit and the 201-million-barrel Sharon Ridge Field operated by ExxonMobil. The company estimates Diamond M has about 43 million barrels and 30 million might be recoverable-too small to light up ExxonMobil's radar screen, but just right for Parallel and Southwestern. The project has good attributes: a sizeable acreage position, good rock and lots of oil still in the ground because of a low recovery factor relative to the offsetting fields. The company plans well-reactivations, deepenings and recompletions, infill drilling, waterflood and later, a CO2 flood. Diamond M was discovered in 1948. In some places the reef is up to 500 feet thick, yet many of the existing wells were only drilled into the upper reaches of the zone, so Tiffin thinks there is more potential with the deepenings. Why is there such a deficit in production, when it has the same rocks and reservoir as its neighbors? Says Tiffin, "The previous operators failed to appreciate the degree of compartmentalization and heterogeneity in the Canyon Reef reservoir. Our development focus will attempt in every way possible to understand and design our rejuvenation plan around the compartmentalization." Parallel has committed to spending $27 million during three years on Diamond M Canyon and Diamond M Clearfork. "These are the largest two pieces of our anticipated $50-million, three-year budget." If it manages to get out 25% of the oil in place, that would be 15 million barrels-or about equal to the amount of reserves the company had in 2003. Parallel tested some ideas by drilling four wells in 2002 to the Canyon Reef at about 6,500 feet. Based on those results, it moved to a second phase, electing to take over field operations in 2003. "This granted us exploitation rights to the shallower Clearfork Field in addition to the Canyon." By midyear it will kick off a new 3-D seismic survey to better image the compartmentalization in both the Canyon (6,500 feet) and Glorietta/Clearfork (2,400 to 3,400 feet) intervals. Major study of the entire field is ongoing. "Our 2004 Canyon budget continues to concentrate on well reactivations and deepenings and infrastructure work. Our shallow plans for 2004 encompass the drilling of 30 infill wells and related workovers in offset wells to begin development on a 10-well-spaced five spot waterflood pattern." Gross reserve targets are 30 million barrels of oil in Canyon and 4.5 million in the shallower Clearfork. Canyon will see waterflood and CO2 while Clearfork will be waterflooded only. "These are two very interesting projects with big potential and a unique deal structure. It's not like we have to find the oil, we just have to figure out the most efficient and profitable means of recovering it."

Recommended Reading

Laredo Oil Settles Lawsuit with A&S Minerals, Erehwon

2024-03-12 - Laredo Oil said a confidential settlement agreement resolves a title dispute with Erehwon Oil & Gas LLC and A&S Minerals Development Co. LLC regarding mineral rights in Valley County, Montana.

NAPE: In Basins Familiar to E&Ps, Lithium Rush Offers Little Gold

2024-02-07 - A quest for sources of lithium comes as the lucrative element is expected to play a part in global efforts to lower emissions, but in many areas the economics are challenging.

From Satellites to Regulators, Everyone is Snooping on Oil, Gas

2024-04-10 - From methane taxes to an environmental group’s satellite trained on oil and gas emissions, producers face intense scrutiny, even if the watchers aren’t necessarily interested in solving the problem.

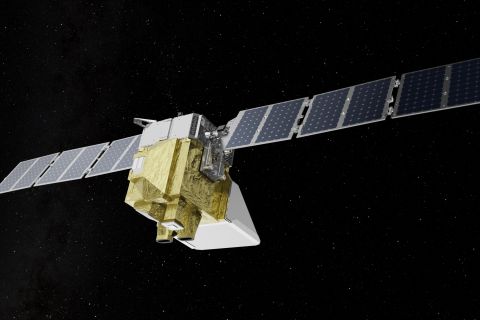

Markman: Is MethaneSAT Watching You? Yes.

2024-04-05 - EDF’s MethaneSAT is the first satellite devoted exclusively to methane and it is targeting the oil and gas space.

Biden Administration Criticized for Limits to Arctic Oil, Gas Drilling

2024-04-19 - The Bureau of Land Management is limiting new oil and gas leasing in the Arctic and also shut down a road proposal for industrial mining purposes.