When building an E&P company, you need capital, assets and a strong business plan. As for the capital, the supply to the oil and gas industry today is greater than at any time in the past 20 years. That was plainly evident from listening to 15 sources of private capital that have raised an aggregate $25 billion, and who offered their investment criteria at the annual Private Capital for Energy forum in Houston, co-sponsored by Cosco Capital Management LLC, New York, and Oil and Gas Investor. The private capital providers are not sitting idly on those funds. Cosco data show that last year these 15 providers participated in 93 financings and monetized 27 of their positions. They still have about $8.5 billion available for investment, said Cosco managing director and founder Cameron O. Smith. The increased amount of capital available and the greater frequency of deal-making have changed the parameters for both capital providers and their E&P clients. "Our average investment size will probably have to go up to account for the larger fund we've just raised," said John Campbell of Quantum Energy Partners in Houston, which closed its $345-million fund this spring. Centurion Exploration Co., a Houston start-up focused on exploration, not acquisitions, and armed with 3-D seismic data as its only asset, was able to raise capital nevertheless. It received a commitment for up to $200 million from Yorktown Energy Partners in New York, even though it had no production or undeveloped acreage as a starting point, partner Geoff Roberts told attendees. (For more on Centurion's funding, see "A Start-Up's Story" in "Here's the Money: Capital Formation 2004," a May supplement to Oil and Gas Investor.) This represents a sea change from the past, as historically private capital providers don't like to fund a pure exploration start-up that has no development opportunities. During the past two or three years, chief executives who get funding have built their start-ups to an intermediate size of $100- to $200 million or so, then sold out to a larger, often public, company that needs production and drilling acreage. The private capital providers, who of late have made very good returns, sometimes as much as five-to-one, are eager to fund them again. That happened to Paul Rady of Denver, who combined private capital with drilling success in the Rockies to build up Pennaco Energy, then sell it to Marathon Oil Corp. for $500 million. After taking a year off, Rady is back as chairman and chief executive of Antero Resources Corp., which was funded with $260 million from three sources: Warburg Pincus, Yorktown Energy Partners and Lehman Brothers. "We chose to get all the money up-front this time, as firepower, rather than getting some capital first and then going back for a series of larger amounts over time," Rady said. EnCap Investments LP, which at press time expected to soon close a fund for at least $725 million, also backs existing management teams more than once. "We have 14 deals funded in our Fund IV, and six of those are repeats," said partner D. Martin (Marty) Phillips. "We'd rather invest $50 million with a group we know well as opposed to investing two $25-million chunks with people we don't know. Besides, the truth is, the investment size does grow as the size of our fund grows." Current deal flow for a strategy of "fund it, build it, sell it" seems to be vibrant. "Sometimes we have a potential buyer in mind even before we fund a deal," said Quantum's Campbell. "With every move, we have to keep the eventual exit in mind." Although private capital providers have a lot of money to place, they are still prudent. "We look for managers who can shift with the times," said Peter Kagan with Warburg Pincus. "We're looking for businesses that can grow 10% to 15% across all commodity cycles." Private equity has several advantages, the speakers said. "Private equity is expensive money with a lot of covenants attached, but across the globe, it is where the most sophisticated money resides, where the fund managers are mature and have a real understanding of the energy business," said John Moon, managing director, Morgan Stanley Private Equity. Billy Quinn, a managing director of Natural Gas Partners, a $1.6-billion family of funds for investment in energy, said, "If you put together a play and take it to industry partners, they're going to try to control it or dictate the speed of it. Private equity is a much friendlier way to go. "Do you want a partner who invests in all your deals, or do you want to be out on the road, selling project by project, rather than devoting your time to what you do best-drilling and producing?" Beneficiaries of private capital discussed their experiences. "Sweat equity is one thing, but real money is more important," said Bill Pritchard, founder of Peak Energy Resources in Durango, Colorado. The start-up will spend about $28 million this year, with three rigs running. Commercial banks could only have funded half that amount, he said, so private equity was a key tool for building value at Peak. The company was formed in 2002 with an initial investment of $10 million from Yorktown Energy Partners. In April 2003, it acquired assets for $45 million. Pritchard advised those who are seeking private capital not to walk away from a term sheet because high-powered egos can't agree on who should run the start-up. "Everybody wants to be the guy, but if somebody is standing there offering to give you $20 million, I wouldn't get hung up on titles," he said. Kurt Talbot, head of the recently formed Goldman Sachs E&P Capital, a mezzanine funding source, said E&P can be a unique sell to investors. "Investors have different perspectives of risk and the problem with E&P is there are so many different types of risk. Industry types think of risk as technical or commodity-related, but investors see more because they compare E&P with other opportunities-they also see credit risks and structural risks. "The basis of competition among capital providers is taking and pricing these risks." Michael Keener, co-founder of Petrobridge Investment Management LLC, also a mezzanine financial source, said, "We have a lot [of covenants]. We control the loan and stay very involved. We have to approve the development plan and require that the plan stays current. This is just good discipline for small companies with a lot of development." Jay Squiers, senior vice president with Prudential Capital Group, which has a total portfolio of more than $2.5 billion, said, "We like to think of ourselves as the purgatory between the commercial banks and the debt market. Today we continue to move toward debt investing but we still include mezzanine." In E&P, the largest risk still lies in drilling results. Roberts at start-up Centurion Exploration was asked what would make a pure wildcat exploration program attractive to private equity. "Nothing," he quipped. However, a strong commodity-price environment combined with a pricey M&A marketplace could help interest private dollars on the exploration side, he added. "I suppose it could happen, but that's as far as I would go." The pursuit of larger margins can sometimes obscure the degree of increasing risk involved. The heightened price of telecom stocks was one example, said V. Frank Pottow, managing director, Greenhill Capital Partners. "When all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail." WHAT NOT TO FUND Private capital providers at the conference were asked about investments they made that didn't work out. Here are a couple of their answers. D. Martin Phillips, EnCap Investments LP "In 1997 there was a robust public market. We backed a privately held company based in the shallow Gulf. We had an experienced team and the deal was for exploration so there was potential for high impact. "Our first mistake was the company was trying to be something it wasn't. We were hoping to arrive at a common view of risk and we never got there. You need a common view of how you're going to make money. Our second mistake was our game plan with development didn't proceed as planned-we had a difference in philosophy. The company took on high-risk projects that didn't work. "Our third mistake-in 1998 prices plummeted and the world changed right in the middle of our investment. Our fourth mistake-we had a management team with immense experience, but it didn't possess the flexibility to adapt. Ultimately we sold it to a public company and all the equity-holders made money, but it sure didn't look like it was going to turn out that way for a while." John Campbell, Quantum Energy Partners "Our worst performance was due to strategy change. We backed a company in Canada to drill mid-range gas wells. It had little success. Management underestimated the hook-up timing. There was a strategy shift to drilling smaller wells with less potential. The company eventually got merged into a larger company. "From this deal we learned that we didn't want to do minority interests. Now we make sure we're viewed as partners, not just a financial backer."

Recommended Reading

Ithaca Deal ‘Ticks All the Boxes,’ Eni’s CFO Says

2024-04-26 - Eni’s deal to acquire Ithaca Energy marks a “strategic move to significantly strengthen its presence” on the U.K. Continental Shelf and “ticks all of the boxes” for the Italian energy company.

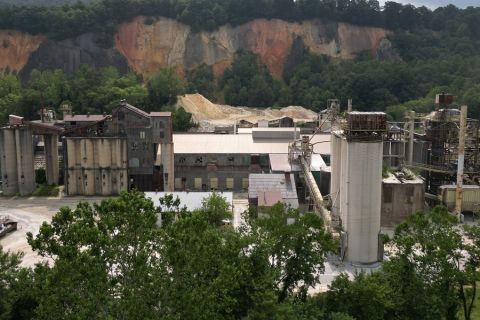

Apollo to Buy, Take Private U.S. Silica in $1.85B Deal

2024-04-26 - Apollo will purchase U.S. Silica Holdings at a time when service companies are responding to rampant E&P consolidation by conducting their own M&A.

Deep Well Services, CNX Launch JV AutoSep Technologies

2024-04-25 - AutoSep Technologies, a joint venture between Deep Well Services and CNX Resources, will provide automated conventional flowback operations to the oil and gas industry.

EQT Sees Clear Path to $5B in Potential Divestments

2024-04-24 - EQT Corp. executives said that an April deal with Equinor has been a catalyst for talks with potential buyers as the company looks to shed debt for its Equitrans Midstream acquisition.

Matador Hoards Dry Powder for Potential M&A, Adds Delaware Acreage

2024-04-24 - Delaware-focused E&P Matador Resources is growing oil production, expanding midstream capacity, keeping debt low and hunting for M&A opportunities.