Ladyfern wells are so mighty that the ground rumbles when they are tested. Their rates are phenomenal-a lone well can flow more than 100 million cubic feet per day. The field is a dream, a company-maker, a career-maker; countless people will spend their entire professional lives in the oil patch and never get close to such stupendous production. What's more remarkable is that the field is onshore in North America, a stone's throw to the continent's web of pipelines and readily accessible to its insatiable gas markets. Ladyfern is straightforward, uncomplicated and about as profitable as a field can get-no intricate, risky drilling procedures, no long-cycle deepwater developments, no predaceous government profit-sharing arrangements. The 3,000-meter wells cost about C$2.4 million each and spew gargantuan volumes of gas requiring minimal processing. Payout is measured in months, not years. According to investment firm Lehman Brothers, in first-quarter 2002 the production from this single field pushed western Canada's volumes up 3% above year-earlier levels. Absent Ladyfern, the first-quarter's average daily volume of 14.912 billion cubic feet (Bcf) for total Canadian gas production would have been down almost 2%. The stunning find, in the oil industry's backyard, surprised many that think onshore elephants are extinct. Nonetheless, there are reasons Ladyfern lay undiscovered for decades. The part of northeastern British Columbia that is home to the field is a remote, muskeg-covered bog. Only when the ground is frozen can work proceed with ease; in summer, two feet of mud, vast stretches of water and swirling clouds of insects make operations nearly impossible. Ladyfern sits in the Chinchaga sub-basin, an arm of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin that lays along the north side of the Precambrian Peace River Arch. During the Paleozoic, a number of carbonate platforms developed in this area. One of these was the Devonian Slave Point, the formation that is so prolifically productive at Ladyfern. The field had its precursors. The first significant Slave Point discovery in the area was Cranberry Field, found in 1974 on the Alberta side of the sub-basin. Cranberry, containing more than 400 Bcf of recoverable gas, was eye opening. It caused many explorationists to take a hard look at the area. The play was pushed westward in 1983, when Hamburg Slave Point "A" Pool was discovered close to the provincial border between Alberta and British Columbia. This find was mammoth-like Cranberry, it held more than 400 Bcf of recoverable reserves, but the per-well flow rates at Hamburg were far higher-and it ignited a frenzy of exploration. Some 200 Bcf in various satellite pools were located in the immediate vicinity, but no other large, discrete fields were found. That lack of success was not for want of effort, for more than 500 wells were drilled to test the Slave Point in the Hamburg area between 1983 and the discovery of Ladyfern. One of these was a near miss-a 1974 well drilled into the Ladyfern accumulation encountered limestone with a tiny bit of porosity in the Upper Slave Point. The operator was not impressed; it decided to run a drillstem test in the Gilwood sands instead and recovered gas and water. Interest in the Slave Point was superceded for a time by favorable results in more pedestrian prospects in the Triassic Halfway and Cretaceous Bluesky and Gething formations. That changed abruptly in early 2000, when news of a gigantic Slave Point discovery began to hit the hockey-league locker rooms in Calgary and Edmonton. A phenomenal find Originally, Ladyfern was a Shell Canada prospect. In November 1999, Apache Canada Ltd. bought Shell Canada's Plains unit; the discovery well was drilled in December. Prior to the closing, Shell had sold interests in the prospect to Murphy Oil Corp. and Beau Canada Exploration Ltd., keeping a 37% nonoperated position for its own account. "Shell had a lot of experience in the Slave Point, and we spent a significant amount of time and effort looking for fields like Hamburg and Cranberry," says Rob Spitzer, a former Shell geologist and now vice president of exploration at Apache Canada. Shell had the Ladyfern lead for quite some time, and had shot a fair-sized 3-D seismic survey over it. The firm also shot a small 3-D project over the Hamburg discovery well, and matched that to the Ladyfern data. "When we compared the 3-Ds it was pretty obvious what we were looking at, although we didn't know Ladyfern would be as big as it is." Operator Murphy Oil spudded the a-97-H/94-H-1 wildcat to the southwest of Hamburg Field, on the British Columbia side. The a-97-H well hit 13 meters of highly porous and partly dolomitized Slave Point at a depth of about 2,800 meters. The discovery tested at a rate of 100 million cubic feet of gas per day, and was tied into a pipeline in April 2000, selling 47 million cubic feet per day. Still, it was not immediately apparent how massive the find actually was. The partners drilled three other tests that winter-a second British Columbia-side well was dry, and two wells drilled in Alberta were capable of making 9- and 2 million cubic feet per day. Good results, but not thrilling. Initially, Murphy owned 33% of the prospect and Beau Canada, 30%; late in 2000, Murphy purchased Beau Canada, upping its position to 63%. Interest in the play spiked in early 2001, when Murphy and Apache announced a string of successful, high-volume wells. The companies also built a 12-inch, 10.6-mile pipeline to carry 160 million cubic feet of gas per day to the Hamburg gas plant in Alberta, operated by Apache. At that time, the partners announced that the gas-charged Slave Point reef at Ladyfern might contain recoverable gas in excess of 300 Bcf Even that whopping estimate turned out to be an understatement. Calgary-based Alberta Energy Co. Ltd., which merged in early April with PanCanadian Energy Corp. to create EnCana Corp., launched a drilling program on some of its 100%-owned leases that it held to the south of the Murphy/Apache drilling. Some years before, the company had acquired 33,000 acres for a shallow Bluesky play. After news of the a-97-H find, it quickly shot a 3-D survey. EnCana's c-6-H discovery well, five miles south of the initial Ladyfern test, flowed at the rate of 60 million cubic feet per day from the Lower Slave Point. The firm successfully completed three more wells during the 2001 winter drilling season; two had initial rates of 50 million cubic feet per day and one, 25 million. EnCana's c-6-H is one of the top three wells in Ladyfern, and the three subsequent wells are among the field's top ten producers. That was not all. To the west of the Murphy/Apache position, Calgary-based Canadian Natural Resources Ltd. also held a 30,000-acre swath of 100% acreage. "We've been working in British Columbia since 1991," says Steve Laut, executive vice president of operations. "We had acquired land for shallow gas plays, and we had held most of it for a long time. We also had a lot of 2-D seismic." Still, some of CNRL's acreage was expiring and it needed to act. In the winter of 2001 the company decided to shoot a 3-D seismic program over its holdings. "We waited to shoot the 3-D until the ground was good and frozen, so we could acquire better-quality data." That decision meant the company had to drill through the spring and summer if it wanted to avoid being drained by offsetting wells. There's no regulatory restriction against drilling in the summer; it's avoided because of costs. "It's very tough-almost unbelievable-how difficult and expensive it is to drill there when it's not frozen." Success was its reward, however, as CNRL's initial c-82-G well, about 2.5 miles southwest of the a-97-H, was capable of producing more than 70 million cubic feet per day. (For more background on Ladyfern's early days, see "Luxuriant Ladyfern," May 2001, Oil and Gas Investor.) The race was on. A complex reservoir Ladyfern is a classic stratigraphic trap in the Slave Point formation. The rocks of interest were deposited in several cycles, says EnCana exploration geologist Jay Harrington. Initially, a series of amalgamated patch reefs grew that were comprised of corals and stromotoporoids, sponge-like organisms that ranged in size from a few centimeters to a meter long. Above the patch reefs, lagoons formed. Next, a series of grainstone shoals and intershoals developed. Finally, a seal of tight carbonates and shales capped the sequence. In the Chinchaga sub-basin, the Slave Point forms a carbonate bank that is indented with local embayments. Cranberry Field lies on one large promontory, while Hamburg Field is a discrete island. Explorationists looking for additional Slave Point fields chased look-alike islands and noses on the platform-Ladyfern is one such nose. But what makes Ladyfern's Slave Point reservoir so hugely prolific is an extra step in its geologic history-the extensive dolomitization of its original rock fabric. The process is best explained by the hydrothermal dolomitization model, originally proposed in 1991 by Jim Reimer and Mark Teare. "This model postulates that hot dolomitizing fluids move up faults and travel outward in porosity zones," says Harrington. A likely contributor to Ladyfern's extensive dolomitization is its location on a splay of the Hay River fault zone. The basement-related, strike-slip fault zone was periodically active, fracturing the Slave Point and providing conduits for the dolomitizing fluids to move up into the formation. "The fluids then leached, brecciated and dolomitized the limestones. Collapse features developed that are difficult to see on 2-D seismic, but which can easily be imaged on 3-D seismic." The process is localized. For instance, the Slave Point reservoir at Cranberry Field has not been dolomitized. Wells in that field produce from limestone facies, generally at rates between 2- and 10 million cubic feet per day. Average porosities are around 5% and permeabilities range up to about 20 millidarices. In contrast, dolomitized reservoirs such as those at Ladyfern and Hamburg can produce 50- to 150 million per day from a single borehole; porosities are as great as 30% and perms can be above a Darcy. Far fewer wells are required because of large deliverabilities-Hamburg will produce more than 400 Bcf from just four wells. Ladyfern is unique in another way. Its carbonate platform has a well-developed northern margin, which is the area where the discovery well was drilled. The porosity in that well is in a grainstone shoal in the upper part of the Slave Point. EnCana's production, in contrast, is further back on the platform and in the lower part of the Slave Point, says Harrington. This portion of the formation is not usually productive, and its addition gives Ladyfern an exceptional amount of reservoir section. Because the dolomitization process is erratic, well quality can vary widely within the field. Various wells have encountered tight limestone, productive limestone, productive dolomite or wet dolomite. Still, each producer appears to be affected by its neighbors, and the overall reservoir quality is such that wells are capable of draining areas much larger than their 640-acre spacing units. "All of the producing wells appear to pressure connected," says engineer Mark Taylor, EnCana's British Columbia group leader. "It's one big tank, although there may not be perfect connections between every well." Ultimate recoverable reserves for Ladyfern are in the range of 500 Bcf to 1 trillion cubic feet (Tcf), says Taylor. Hydrocarbon pore-volume mapping can put more than a Tcf in the field, while worst-case interpretations of pressure data push the range toward the lower end. Most people are comfortable with the middle of the range, so 750 Bcf is an oft-quoted figure. Intensely competitive If one company had owned Ladyfern Field, there's no question that fewer wells would have been drilled. Once companies realized that the drainage radii of the wells were so large, they pulled out all the stops to bring as much production onstream as quickly as possible. No company wanted to lose its gas to another's sales meter. The law of capture was in full force. Energetic drilling programs were mounted, along with construction of gathering, treating and compressing facilities and large-diameter pipelines. (The gas has very small concentrations of H2S and CO2 that need to be dealt with; otherwise it only requires minor dehydration.) In the space of a year, more than C$400 million was poured into what had been the middle of nowhere. By the close of March 2002, some 40 wells were producing 730 million cubic feet of gas per day from Ladyfern. Apache Canada's share totaled about C$100 million at Ladyfern, says Floyd Price, Apache Canada president. Murphy and Apache drilled four wells in 2000, 15 in 2001, and 10 by late April this year. To date, the two firms have 24 producing wells at Ladyfern and are making 360 million cubic feet per day. "Everybody has played the game hard, trying to get their wells and infrastructure in as quickly as possible," says Price. "We even decided to drill in the fall, which is unheard of in this part of the world, because we wanted to be ready to use the new pipeline capacity to the Owl Lake #3 meter station this spring." For its part, EnCana now operates nine producing wells in Ladyfern, and is making 150 million cubic feet per day. It drilled nine wells in 2001, put in a gas-processing plant with capacity of 170 million cubic feet per day, and laid a 10-inch spur to tie into TransCanada's Owl Lake South #2 station in Alberta. This year, including an exploration test south of the field, it drilled seven wells. Its capital costs now stand at about C$130 million. "Ladyfern gas production is some of the lowest-cost production in all of EnCana," says Randy Eresman, president of onshore North America. Today, the prime locations within the field have almost all been drilled, although the boundaries are still being probed, he says. "We have had surprises, both positive and negative, within the interior part of the reef that we couldn't fully define with the seismic. We've established the water contact in the field, but we don't yet know if we have a solution-gas drive or water drive." CNRL has drilled 16 wells, 10 of which are within the Ladyfern pool, and is producing 220- to 225 million cubic feet per day from nine of those, says Laut. "We had essentially no production this time last year." Through the end of 2001, the company had spent about C$118 million on the play. In early March 2002, CNRL also completed a gas-processing plant and a 20-inch sales pipeline to connect Ladyfern to TransCanada's Owl Lake #3 station. The line, operated by CNRL and owned by a producers' group, has a capacity of 600 million cubic feet per day. The intense competition that led to the lightening-speed drilling and installation of infrastructure stressed each of the participants, all of whom were keenly aware that the web of wells, pipes and stations could quickly become passe. After all, Ladyfern is a flash-in-the-pan as fields go. It will likely begin a sharp decline this year, and its overall life span is estimated at just four to six years. Unless another twin lies nearby, the facilities constructed with so much expense will languish. Consequently, the major owners in the field have pounded out a production-sharing agreement. The producers wanted to control the growth of the surface infrastructure by reining in production. Normal procedure would have been to unitize the field, which requires that the size of the reserves be defined. "That task was extremely difficult at Ladyfern, because of the variability of the distribution of the dolomite. We had a short time-frame, and we knew traditional unitization would probably never be accomplished," says EnCana's Eresman. Instead, the owners worked out formulas based on well productivity. Under the production-sharing agreement, field production is now capped at 785 million cubic feet per day. The next phase of the agreement will be to restrict the amount of compression that will eventually be installed. Ladyfern is much quieter now. Unlike last summer, little drilling is likely to occur after breakup this year. The field is mostly developed and the production-sharing agreement is working, so the operators are not inclined to fight the high costs, horrendous mud and mosquitoes of summer in the muskeg. Exploration moves outward Exploration for another Ladyfern, and for satellite pools in the immediate vicinity of Ladyfern, is now the top priority. Even by Canadian standards, northeastern British Columbia has not been heavily prospected. Reasons vary: For one, British Columbia is more expensive and difficult to work in than Alberta, although the province is making attempts to streamline its regulatory process. Also, because the area is only lightly developed, drilling costs can be quite a bit higher than for a well of similar depth in Alberta. There are issues with the First Nation tribes as well, although most of the objections of the aboriginal peoples have been sorted through. "Now the focus is to find new pools," says CNRL's Laut. The company is already actively exploring; in addition to its development drilling, it plans to test five exploratory prospects this year. "We think there are more fields out there, but they won't be as big as Ladyfern." EnCana is looking further as well. "We're expecting some smaller reef growths around the edges of Ladyfern, and some of those discoveries are already being made," says Eresman. The hunt is also on for the next embayment and the appropriate setting for another Ladyfern: "We know now that 2-D seismic is not able to properly locate the next major reef, so we'll need much more 3-D." Apache's Price agrees: "We're all looking for another Slave Point discovery. We're going to see a lot of 3-D shooting in the area; we're shooting three programs ourselves." Operators such as Devon Canada Corp. have already enjoyed some good fortune. Northstar Energy Corp., which was acquired by Devon in 1998, has been active in the Hamburg area for about a decade, notes president and chief executive officer John Richels. Typical, non-Ladyfern Slave Point reefs range in size from 5- to 30 Bcf, and Devon has had success over the years picking these out on seismic. The company holds some 185,000 acres of land in the Chinchaga sub-basin, including a significant amount of land near Ladyfern. In 2001, Devon partnered with Murphy and San Antonio-based Abraxas Petroleum Corp. on a large 3-D seismic program over a portion of its acreage. (Abraxas, through its Canadian subsidiary Grey Wolf Exploration Inc., owns an average 32% working interest in 32,000 acres.) This year, Devon kicked off a five-well exploratory program about 10 to 15 miles north of Ladyfern. "There are anomalies on our acreage, which are separate from Ladyfern but have the same seismic characteristics," says Richels. At press time, the company had run pipe and was completing at least two of its Slave Point wildcats, which were expected to be on production shortly. No other information has been released. Devon has also shot two other large 3-D surveys. One targeted prospects around Hamburg Field, near where the company operates and owns a 60% interest in a gas plant. It shot a third survey to the west of Ladyfern in an area called Wildmint, where Murphy and Apache also have a prospect. Like the other operators, Devon is interpreting its new data, making its plans for mid-December when drilling can begin again. Says Richels, "The whole area west of the 5th meridian in Alberta and right up to the mountains in British Columbia has not been heavily prospected. Certainly, it's reasonable to assume that there are more Ladyferns out there." Happy hunting!

Recommended Reading

Ithaca Deal ‘Ticks All the Boxes,’ Eni’s CFO Says

2024-04-26 - Eni’s deal to acquire Ithaca Energy marks a “strategic move to significantly strengthen its presence” on the U.K. Continental Shelf and “ticks all of the boxes” for the Italian energy company.

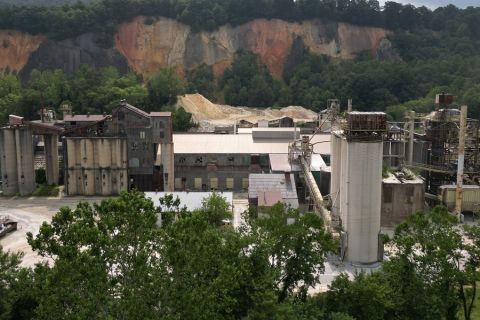

Apollo to Buy, Take Private U.S. Silica in $1.85B Deal

2024-04-26 - Apollo will purchase U.S. Silica Holdings at a time when service companies are responding to rampant E&P consolidation by conducting their own M&A.

Deep Well Services, CNX Launch JV AutoSep Technologies

2024-04-25 - AutoSep Technologies, a joint venture between Deep Well Services and CNX Resources, will provide automated conventional flowback operations to the oil and gas industry.

EQT Sees Clear Path to $5B in Potential Divestments

2024-04-24 - EQT Corp. executives said that an April deal with Equinor has been a catalyst for talks with potential buyers as the company looks to shed debt for its Equitrans Midstream acquisition.

Matador Hoards Dry Powder for Potential M&A, Adds Delaware Acreage

2024-04-24 - Delaware-focused E&P Matador Resources is growing oil production, expanding midstream capacity, keeping debt low and hunting for M&A opportunities.