Traditional oil and gas players looking to tap into another potential revenue stream as the world goes greener are turning to lithium extraction in the U.S., relying on drilling and other expertise to enter new markets.

The lightweight metal is a key ingredient for rechargeable batteries used to power items such as laptops, cell phones and—most notably for the energy transition—energy storage and electric vehicles (EVs).

Given President Joe Biden’s goal of having 50% of all new vehicle sales be electric by 2030, a power sector free of carbon pollution by 2035 and other emissions reductions objectives, U.S. demand for lithium batteries is expected to increase by nearly six times by 2030, according to an industry report from Li-Bridge, a public-private partnership coordinated by the Argonne National Laboratory. In the U.S. alone, the market for lithium battery cells is forecast to hit $55 billion per year by 2030.

Exxon Mobil has jumped into this market in the Smackover region of Arkansas.

“We’re excited about the opportunity and really excited to deploy our skills and capabilities in this new area,” Patrick Howarth, lithium global business manager for Exxon Mobil Low Carbon Solutions, told Hart Energy. “We think we’ve got a pretty unique set of capabilities across this value chain.”

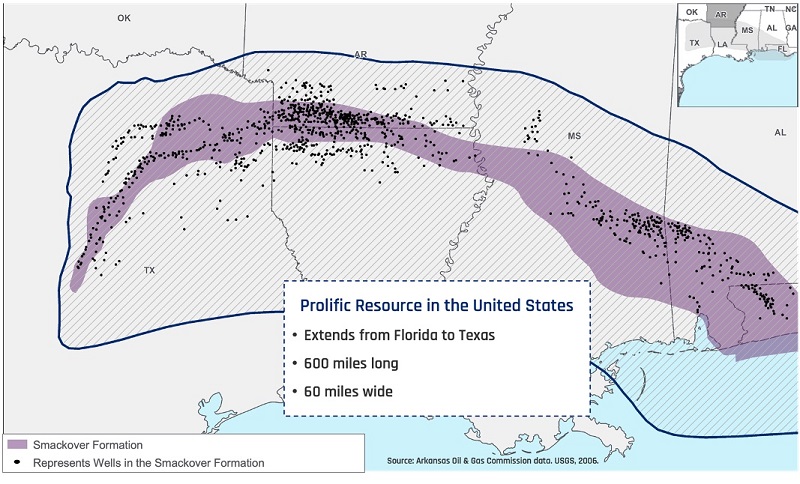

Lithium resources, including in the Smackover Formation that spans from Texas to Florida, could be ripe for development.

The U.S. has identified an estimated 12 million tons of lithium resources in the nation from continental, geothermal and oilfield brines as well as claystone and igneous rock, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. The nation is home to only one lithium mine, but efforts are underway to boost domestic supplies of critical materials and manufacturing capacity.

The Smackover Formation in Arkansas was known for its oil production, but the bromine-rich region has attracted companies to brine due to its high concentration of lithium. Brines from wells in southwestern Arkansas’ Columbia County contain as much as 445 parts per million lithium, according to Arkansas’ Office of the State Geologist.

Growing interest

Exxon Mobil entered the region to begin drilling in 2023, joining Albemarle, the world’s largest lithium producer, and Canada-based Standard Lithium, which has two projects in southern Arkansas near the Louisiana state line.

The supermajor plans to lean on its conventional oil and gas expertise, drilling about 10,000 ft underground to access lithium-rich saltwater. It will then use a process called direct lithium extraction (DLE)—also used by Standard and Albemarle—to separate lithium from the saltwater, which will be reinjected to the reservoir. The extracted lithium will be converted onsite into battery-grade material, the company said.

The method produces fewer emissions and requires less land than the traditional method of extracting lithium via hard rock mining. It also doesn’t require as much land as lithium brine extraction in evaporation ponds, where brine sits for several months or years as the sun evaporates most of the liquid content, ultimately leaving behind lithium and other metals. The brine, with its higher concentration of lithium, is then pumped to a facility for processing.

“The world has two different sources of lithium today. It’s either hard rock or from brine. Most of the brine is shallow brine within Latin America, and they use evaporation as the main mechanism to concentrate up the lithium and remove impurities,” Howarth said.

“Within Arkansas, we don’t feel that there’s an opportunity for evaporation there. And frankly, we see DLE as being very advantageous from an environmental footprint perspective,” he added. “So, significant benefits from a land use or water use perspective but then also substantially lower carbon intensity versus hard rock mining.”

Exxon Mobil aims to begin lithium production in 2027. Standard Lithium is targeting first production of battery-quality lithium carbonate in 2026 at its Phase 1A Project at LANXESS Corp.’s South Plant near El Dorado, Ark.

The year 2023 saw increased activity in the lithium brine space as companies such as Standard Lithium, for example, unveiled positive feasibility studies and strong project economics—an after-tax NPV of $550 million and IRR of 24%, assuming an 8% discount and long-term price of $30,000/ton for battery-quality lithium carbonate for its Phase 1A project in Arkansas.

While Arkansas may be considered an emerging epicenter for potential lithium brine development and Nevada is the hotbed of lithium brine activity in the U.S., Texas is also in play. Standard Lithium reported in October 2023 that it delivered the highest-ever North American lithium brine grade at 806 mg/L in East Texas.

Oil and gas companies along with water midstream companies are showing interest in pursuing lithium in northeast Texas, according to Reagan Marble, a partner with the Jackson Walker law firm.

Legal uncertainty lingers

However, newcomers looking to get in on the action should consider a few things beforehand. Topping that list is who owns the lithium, Marble said.

“Unfortunately, in Texas, we don’t have a clear answer to who owns lithium. We do know that brine is a part of the surface estate and, more particularly, the groundwater in the state is owned by the surface owner,” Marble said. A legal case touches on the issue but the case mainly focuses on extracting salt—defined as a mineral in Texas—for commercial use. It has left some companies interested in entering lithium extraction in Texas wondering whether to pursue leases from surface owners or mineral owners.

“There are a lot of issues that pop up on your due diligence checklist as you’re trying to figure out which one to go after,” Marble said. “And to be candid, I don’t think we are going to see quite the land grab that Texas could be experiencing at the moment until we have a legislative solution to who owns the lithium.… [The issue] came too late during our extended legislative sessions to really address it, and I don’t think it’s going to be addressed until 2025.”

In Arkansas, such issues are resolved because the state has a well-established brine production industry that has been around since the 1950s. Lithium extraction is regulated under Arkansas’s Brine Production Act and the state’s Brine Production Regulatory Program.

With case law unclear in Texas, Marble advises oil and gas operators with active leases not to just go out and start exploring for lithium on those leases.

“There’s not a ton of case law [in Texas] on how you look at the ordinary and natural meaning of the term mineral. And quite frankly, until there is a legislative solution, there surely won’t be a legal solution in court interpreting whether lithium is in the ordinary natural meaning of the word mineral or falls under the surface destruction test,” Marble said. “We just don’t know.”

However, he added companies could avoid the ownership issue by pursuing what is known as fee owners, or those who own both the surface and the minerals.

Still, lithium development in Texas “will surely be stunted until we solve this issue,” he said.

Extracting lithium from produced water that comes from the wellbore during oil and gas production is another area that could attract interest from operators looking to find value in oil and gas waste. Areas that come to mind for Marble include parts of the Haynesville Shale in the East Texas area.

“I think the fight eventually will be if that produced water starts to be processed through direct lithium extraction, whether that was a right that an operator has under an oil and gas lease,” Marble said. “I find it hard to believe that when the legislature put together the oil and gas waste statute and included produced water, that they meant to give companies the windfall of lithium one day.”

Legal issues aside, the future appears promising for lithium extraction from brine. While lithium is “kind of the lowest hanging fruit” for electricity and battery storage, brine could help source other emerging battery technologies.

Marble compared brine to natural gas. Oil producers at times viewed natural gas as a waste product until Henry Hub natural gas spot prices shot up to $6/Mcf.

“You may see that in some of these brine production leases one day, maybe where they are going after lithium, then someone cracks the sodium ion technology wide open and all of a sudden people are buying salt from the brine,” Marble said. “I think there is a world of endless possibilities.”

Another route

In the Marcellus Shale, Eureka Resources has been receiving wastewater from natural gas companies, extracting minerals from it and generating clean water, Eureka Resources Chief Commercial Officer and CFO Chris Frantz told Hart Energy. The company was formed in 2008 with a business model of grabbing the sodium chloride and treating the rest of the wastewater.

According to Eureka’s website, the company’s products include pure water, salt, calcium chloride, oil and methanol. Processes used include an exclusive mechanical vapor recompression distiller evaporation technology, which is used to separate particles from the water, resulting in distilled water. Vacuum crystallization, a method that evaporates water from minerals, is used to extract minerals from purified brine. It’s the same technology used by salt producers, the company said.

Eureka’s focus has turned to lithium in recent years. Working with technology partners and academics, Frantz said the company learned a lot about its brine and the DLE process.

“We also learned that that’s [DLE] not the right solution for us because it’s a slow process. What we want to do is we want to scale up to high volumes and get lots of lithium quickly,” he said.

The DLE process is difficult when working with complicated brine containing many different types of metals, such as in the Marcellus. While the DLE approach plucks out lithium and leaves everything else, Eureka takes the opposite approach and uses methods similar to those it has carried out for years to remove metals from wastewater, Frantz explained. The most prevalent salt is removed, followed by the next and the next until lithium is the end product.

“It took us two and a half years to figure that out,” he said.

Working with partner SEP Salt & Evaporation Plants at a pilot plant in Europe, Eureka celebrated a milestone in 2023: the successful extraction of 97% pure lithium carbonate from oil and natural gas brine from production activities. The recovery rate was up to 90%, the company announced in July 2023.

“We made actual lithium carbonate that meets a technical grade specification at the moment suitable for battery manufacturers,” Frantz said.

Currently, the company is raising funds to expand its existing facilities in Pennsylvania to add lithium to its list products from wastewater.

“Based on our current volumes, we’re projecting about 500 metric tons per year of lithium carbonate,” he said. “We’re also simultaneously working with a partner in the oil and gas space for a brand-new facility in another part of the state that would be about 10 times the size of what we currently have.”

A third-party investor is already working on locations in other basins where the technology can be used, Frantz added.

Recommended Reading

E&P Highlights: March 15, 2024

2024-03-15 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including a new discovery and offshore contract awards.

The Need for Speed in Oil, Gas Operations

2024-03-22 - NobleAI uses “science-based AI” to improve operator decision making and speed up oil and gas developments.

Deepwater Roundup 2024: Americas

2024-04-23 - The final part of Hart Energy E&P’s Deepwater Roundup focuses on projects coming online in the Americas from 2023 until the end of the decade.

TotalEnergies Starts Production at Akpo West Offshore Nigeria

2024-02-07 - Subsea tieback expected to add 14,000 bbl/d of condensate by mid-year, and up to 4 MMcm/d of gas by 2028.

Well Logging Could Get a Makeover

2024-02-27 - Aramco’s KASHF robot, expected to deploy in 2025, will be able to operate in both vertical and horizontal segments of wellbores.