(Source: Exxon Mobil Corp.)

As capex budgets for the five major integrated oil companies are historically a harbinger of the energy industry’s future, a research firm claims its recent finding could signal “a mature industry in decline.”

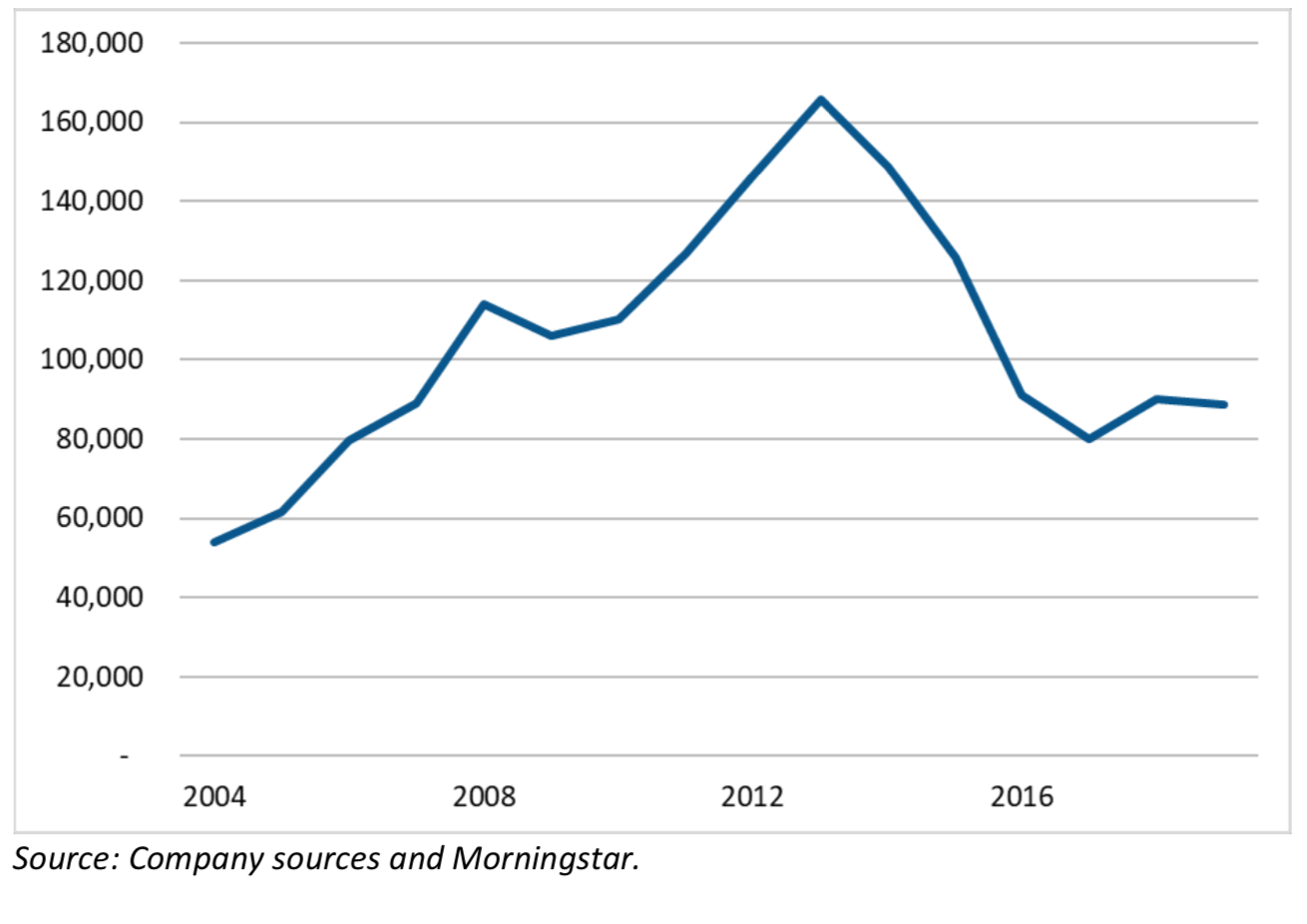

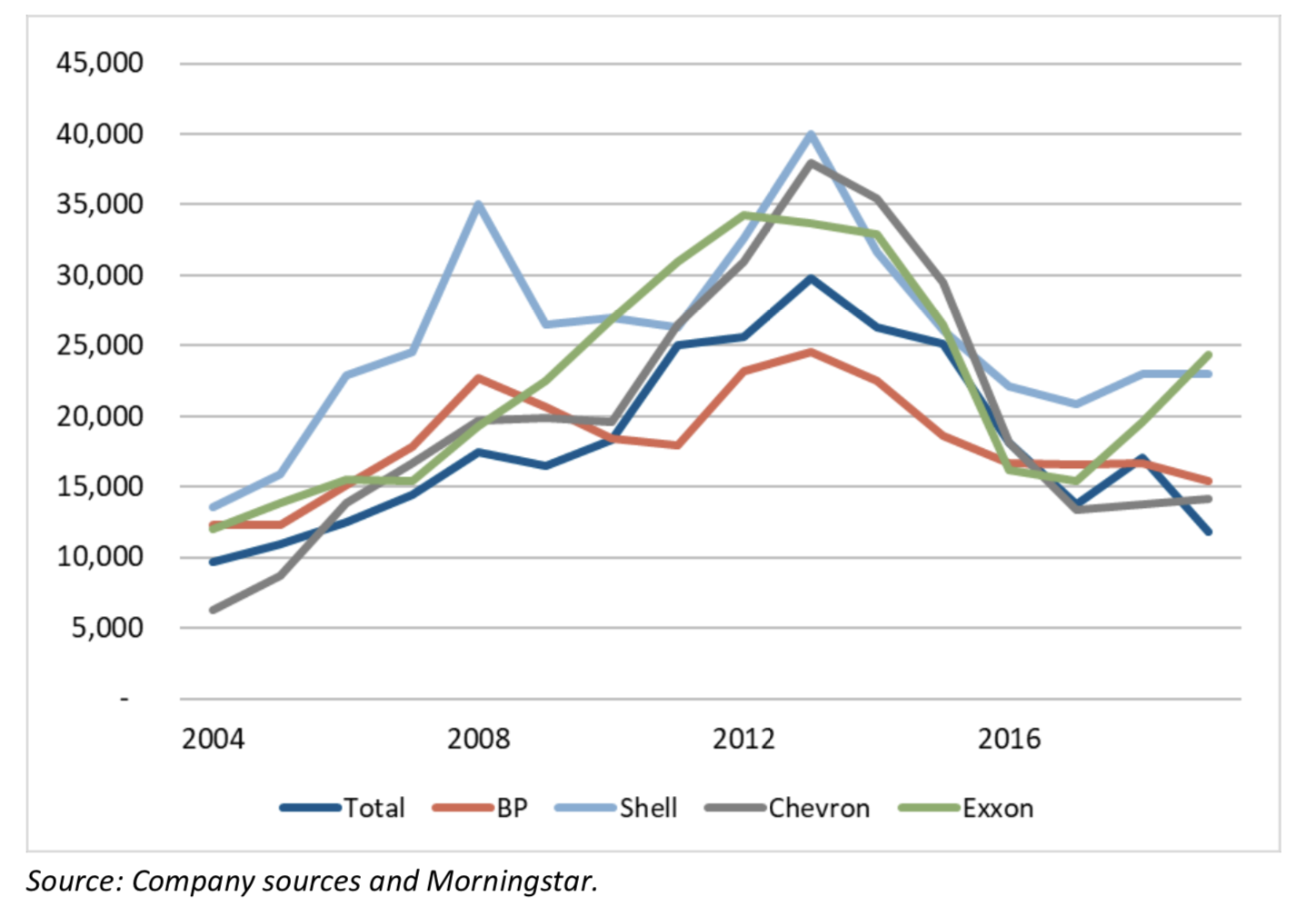

The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) found that capital spending by Exxon Mobil Corp., Chevron Corp., Total SA, BP Plc and Royal Dutch Shell Plc in 2019—worth a combined $88.7 billion—was the lowest amount since 2007. The energy supergiants last year spent just half of what they did in 2013, when their operations distributed $165.9 billion worldwide.

“Diminishing capex should worry investors and serve as a warning that the oil and gas industry is not the cash cow it used to be,” wrote Kathy Hipple, IEEFA energy financial analyst and lead author, in a Feb. 26 briefing note. “Traditional businesses, like oil and gas exploration and production, refining and petrochemicals are all showing signs of stress.”

Not all the majors reacted with sharp capex cuts, however. Exxon Mobil’s budget in 2019 was 93% of its 10-year average of $26.1 billion. Meanwhile, Chevron’s was $14.1 billion, about 60% of its decade average, and Total’s fell to just over half its 10-year average.

After dropping sharply in 2014, Exxon Mobil’s spending has been rising, in fact, with $24.4 billion invested last year. According to the institute, the Irving, Texas-based company plans to expand capex this year to more than $30 billion, “in what has been described as a counter-cyclical strategy.” (Update: Exxon Mobil CEO Sticks To Spending Targets As Oil Prices Tumble)

Commodity prices are the determining factor for oil and gas companies’ spending and health regardless of whether they are majors or small independents. The industry is still working to recover from the fall in oil prices from more than $100/bbl in 2014 to $29/bbl in 2016. Gas prices at $3/MMBtu are in even worse shape. These factors mean the universe of profitable projects shrinks significantly.

“The industry claims it is motivated by capital discipline and higher levels of diligence, but another explanation is a lack of viable investment prospects,” Hipple continued. “The decline in capex indicates an industry with lower production levels going forward and a smaller return on capital invested.”

The IEEFA note also cautioned that the petrochemicals industry, which used to protect the integrateds to some extent, can no longer be counted on as a buffer. Chemical margins fell in 2019 and the financial outlook worldwide is “at best, mixed.”

“The days of consistent, long-term 20% returns are behind them, and unlikely to return,” Hipple wrote. Further, investors are no longer focused on reserve replacement but rather on cash flow and profits. “Free cash flow has become the crucial metric.”

IEEFA also discussed the effects of renewables and climate change pressures on the fossil fuel industry. “The capital markets are shifting toward two energy economies,” Hipple wrote—one based on fossil fuels and the other, renewables. The majors’ talk about investing in renewables does not always match their walk.

“Investments in renewable energy have been minimal,” Hipple added in the note, “even among the European oil majors—Shell, BP and Total—that have made public announcements about their efforts to embrace new energy initiatives.”

One of the stumbling blocks is the 6% to 12% returns on investment (ROI) typical in renewable energy, vs. the 20% or more ROIs for oil and gas in days gone by.

Recommended Reading

Chevron Hunts Upside for Oil Recovery, D&C Savings with Permian Pilots

2024-02-06 - New techniques and technologies being piloted by Chevron in the Permian Basin are improving drilling and completed cycle times. Executives at the California-based major hope to eventually improve overall resource recovery from its shale portfolio.

Pitts: Heavyweight Battle Brewing Between US Supermajors in South America

2024-04-09 - Exxon Mobil took the first swing in defense of its right of first refusal for Hess' interest in Guyana's Stabroek Block, but Chevron isn't backing down.

Exxon Versus Chevron: The Fight for Hess’ 30% Guyana Interest

2024-03-04 - Chevron's plan to buy Hess Corp. and assume a 30% foothold in Guyana has been complicated by Exxon Mobil and CNOOC's claims that they have the right of first refusal for the interest.

Exxon Ups Mammoth Offshore Guyana Production by Another 100,000 bbl/d

2024-04-15 - Exxon Mobil, which took a final investment decision on its Whiptail development on April 12, now estimates its six offshore Guyana projects will average gross production of 1.3 MMbbl/d by 2027.

Stena Evolution Upgrade Planned for Sparta Ops

2024-03-27 - The seventh-gen drillship will be upgraded with a 20,000-psi equipment package starting in 2026.