The British Columbian Ministry of Energy & Mines is working on a campaign to spark interest in drilling off the provincial coast, which hasn't been an exploration hotspot since 1967-69. At that time, Shell Canada drilled 14 wells from Barley Sound north through Queen Charlotte Sound and Hecate Strait, and several other companies also had exploration licenses. A few years later, activity was suspended due to environmental concerns, First Nation native Canadians' land claims and other issues. But interest in waters off the coast has not gone away; the potential of 42 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of reserves, in the burgeoning North American natural gas market, continues to intrigue E&P companies. "Will drilling begin?" Steven Paget, an E&P analyst with FirstEnergy Capital Corp., Calgary, asks. "I'm not even sure we've seen the beginning of that legal battle. It could begin in the last two years of the decade-maybe 2008-10." Provincial government officials have brought their recently won bid for the 2010 Winter Olympics into the play. "We hope to light the torch at those Olympics with gas from our offshore energy industry," Rick Thorpe, British Columbia minister of competition, science and enterprise, told E&P executives at a program in Houston recently. Michelle Harries, senior media advisor, western Canada upstream, Petro-Canada, says, "It's an interesting area to us because it's one of the last frontiers of Canada with unknown potential. We're monitoring the area very closely." Petro-Canada is among E&P companies with offshore leases, which have been frozen since the moratorium. It is waiting for a final determination on the issue. "We don't want to ruffle any feathers," Harries says. "We want to make sure there's a clear path." Others with pre-moratorium licenses include Shell Canada Ltd., Chevron Canada Resources Corp., ExxonMobil and Unocal. Shell Canada Ltd.'s 14 wells were drilled between 1967-69 off Barkley Sound, Vancouver Island, in 70 to 556 feet of water. Seven of the wells were off the Tofino coastline, and the rest were in the marine portion of the Queen Charlotte Basin. The greatest range of water depth was in the Queen Charlotte area; two wells were in water so shallow the rig was sitting on the sea floor. During the exploration program, the rig reportedly experienced seas of 80 feet and winds of 70 miles per hour off Vancouver Island. One rogue wave was approximately 100 feet in Hecate Strait. Non-commercial amounts of oil were found off the Queen Charlotte Islands, and some gas shows were found off Tofino. Chevron Canada Resources acquired its leases in 1969 from Shell, but the moratorium was enacted before it began drilling. Although Chevron's Canadian focus is on the western Arctic and the east coast, spokesperson Dave Tommer says the company is keeping an eye on British Columbia. "We're continuing to monitor discussions in B.C. But any decision to lift that moratorium must be made between federal and provincial agreements." Tommer doesn't see that happening in the near future. Neither does British Columbia's energy and mines minister, Richard Neufeld. "It would be like Texas working with the [U.S.] federal government over Gulf waters," he says. "Would that happen overnight? No. I call [the pace at which federal governments move] glacial speed. We'd like to work a little faster, but we're caught between a rock and a hard spot." A scientific review panel was appointed in 2001 to determine if offshore resources could be extracted in a scientifically and environmentally sound, responsible manner. The panel concluded there is no scientific reason to maintain a coastwide moratorium. Yet the controversy to lift the ban continues. Despite the myriad advances made in offshore technology since the moratorium was imposed, the same arguments are being made by the same critics. Environmental groups say development offshore British Columbia poses a huge risk to marine life and the fishing industry, and the 1989 Exxon Valdez spill on nearby Alaska's shore is still fresh in their minds. Shortly after the Valdez disaster, British Columbia imposed its own provincial moratorium on drilling, fearful something similar could happen in its waters; 14 years later, the fear seems to be lingering for some, but Neufeld wants to separate the incident from his goals. "The Exxon Valdez, piloted by a drunk captain, has nothing to do with drilling offshore British Columbia." The other leading argument against drilling comes from First Nation members, who claim ownership of some of the lands involved and refuse to allow exploration to begin until those claims are settled. In an attempt to quell the controversy, Herb Dhaliwal, Canadian minister of natural resources, whose office is responsible for the administration of federal offshore lands, announced in March that the government would begin a year-long, two-phase process to determine when and if drilling should begin offshore British Columbia. Though the government's review is covering only the Queen Charlotte Basin-possibly the richest of the province's four offshore basins, with an estimated potential of 26 Tcf of gas and 9.8 billion barrels of oil-the government's decision on lifting the moratorium is expected to apply to all offshore British Columbia. The province is currently Canada's second-largest producer of gas-1.1 Tcf per year-and opening offshore waters to exploration and production could prove a boon. Bill Gwozd, vice president, gas services, for consulting firm Ziff Energy Group, Calgary, says he recognizes the impact drilling offshore would have for the province's economy, but advises companies eager to get started to exercise caution. "British Columbia contributes 10% to 15% of Canadian natural gas. [Drilling] would only add to the contribution...but it's not an area in terms of huge potential in the short-term. [It] is partially off our radar screen...until 2010 or beyond. The history is always against us for accelerating projects." Neufeld agrees that pushing too hard for unrealistic goals can be detrimental. "The quickest way to keep the moratorium is to say 'We're drilling tomorrow.'" David Anderson, Canada's environment minister, is wary that a lot of fuss is being made about something that might not even be an issue. He has warned the energy industry will have to pay the costs, estimated at C$120 million, of assessing the environmental risks of drilling. This may turn off potential leaseholders. "The companies would have to believe extremely sizeable resources [are] there," Paget says. "Shell did that with [the] Onondaga [well] on the east coast, and that was C$80 million. Whether they're willing to do that in a field with no proven reserves is yet to be seen."

Recommended Reading

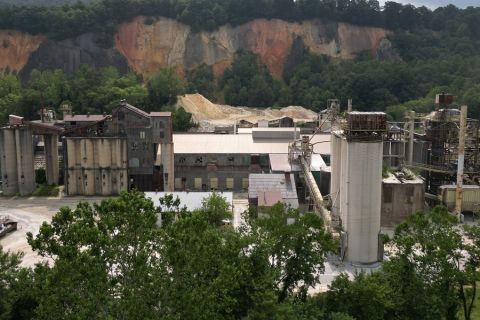

Apollo to Buy, Take Private U.S. Silica in $1.85B Deal

2024-04-26 - Apollo will purchase U.S. Silica Holdings at a time when service companies are responding to rampant E&P consolidation by conducting their own M&A.

Talos Energy Sells CCS Business to TotalEnergies

2024-03-18 - TotalEnergies’ acquisition targets Talos Energy’s Bayou Bend project, and the French company plans to sell off the remainder of Talos’ carbon capture and sequestration portfolio in Texas and Louisiana.

EQT, Equitrans to Merge in $5.45B Deal, Continuing Industry Consolidation

2024-03-11 - The deal reunites Equitrans Midstream Corp. with EQT in an all-stock deal that pays a roughly 12% premium for the infrastructure company.

Continental Resources Makes $1B in M&A Moves—But Where?

2024-02-26 - Continental Resources added acreage in Oklahoma’s Anadarko Basin, but precisely where else it bought and sold is a little more complicated.

Diversified Energy Buys NatGas Assets in Runup to LNG Exports

2024-03-19 - Diversified Energy will pay $386 million to buy 100% interest in Oaktree Capital Management’s assets in Oklahoma, East Texas and Louisiana.