Despite what people might believe about themselves and their individual abilities, it is generally accepted that most things are easier to accomplish with a team. No one is great at everything. Whether it’s completing a project for work or studying for a graduate exam, it’s hard without help and the benefits that come when complementary skills work together. This axiom also holds true in the oil and gas field. In flow assurance, it takes multiple processes working in concert to get the job done.

Any number of reasons can stop a well from flowing smoothly. Both organic and inorganic material can block a pipe and pose risks to safety, the environment and an operator’s bottom line.

“Our customers, which are mostly E&P-type companies, are making these massive investments on the drilling and exploration side. And overall, production is kind of the cash register. Without flow assurance, we risk that revenue flow,” Randy Guliuzo, flow assurance global product line manager at Baker Hughes, told Oil and Gas Investor.

Typically, flow is restricted by a combination of one or more things: paraffin, asphaltene, hydrates and scale.

Paraffins are waxes derived from the fatty components of crude oil and appear when the temperature in the pipe decreases to a certain level, restricting flow within the pipe and increasing the viscosity of crude oil. Asphaltenes are the dissolved solids components of crude oils and, despite being important in the oil field, they can foul well perforations, tubing valves and heat exchanges, as well as cause wellbore reservoir damage due to permeability or wettability challenges.

Hydrates—compounds in which gas molecules are trapped within a crystal structure—occur in environments with high pressure and low temperature. They can plug tubing and flowline and also lead to frozen wellheads. Scale, which is similar to mineral buildup on a bathroom faucet, appears when waters with incompatible chemistries are mixed and temperature and pressure change. It can lead to near-wellbore reservoir damage and permeability changes, fouling of perforations, well tubing, and valves and production decline.

Each of these obstacles can appear during oil and gas operations and cause billions of dollars worth of damage.

“Deferred production costs companies billions of dollars per year. So, if we can prevent deferred production by just preventing these sources of deposition and flow, that's going to be very profitable for our customers,” Rebecca Lucente-Schultz, chemical technologies director of flow assurance at ChampionX, told OGI.

Defeating the “Four Horsemen” of Flow Assurance takes a combined effort. Baker Hughes, ChampionX and other operators are developing an array of inhibitors, dispersants and other chemicals that can kill two, three, or even four birds with one stone.

“A really big area for flow assurance is developing combined, multifunctional products,” said Lucente-Schultz. “Logistically, it’s important because sometimes you don’t have a place to store two or more separate volumes of chemicals. And so, multifunctional products allow you to have the same, or sometimes better, functionality in a smaller space.”

ChampionX develops combination chemicals or multifunctional products through what Lucente-Schultz calls the most “critical” part of her work—testing.

“If you’re not using the right test method, then you have no idea if the product you’re developing is going to get you the right performance in the field,” she said.

The different tests determine which flow management system to employ in conjunction with others, whether it’s dispersants that aid in breaking up solids and liquids or inhibitors that can mitigate paraffin and corrosion, which is another prevalent problem.

“We produce chemicals, and part of what makes that challenging is making sure that the chemicals we’re producing here in the lab are going to perform in the field,” Lucente-Schultz said. “There are aspects from the field that we’re incorporating into the test methods we develop, such that we can make sure the products that are performing in our lab tests are also going to perform in the field.”

Lab and field

Lucente-Schultz’s thought process is evident in ChampionX’s PARA01975A solution, a combination paraffin and corrosion inhibitor, which was developed by eschewing the commonly used, but outdated “cold finger test” in which a metal “finger” simulates the pipe’s inner wall, in favor of developing paraffin inhibitors and instead adopting the new PARA-window method.

“[PARA-window] allows us to look at paraffin fouling in real time as it’s occurring rather than relying on the end of the test,” Lucente-Schultz said. “It allows us to look at more realistic test conditions, and that allows us to look at the very first layer of paraffin that’s forming, which is really critical in the deposition process. We believe that's one of the reasons why it’s so effective.”

While in-lab testing is important to Baker Hughes, engineers have a slightly different view on what the most valuable portion of their flow assurance projects: all on-site monitoring is typically focused on putting the product in the field and learning and adjusting once it is there.

“In-field monitoring and the testing associated, once the application has begun, generally circles around is the product working to meet the KPIs [key performance indicators] that us and the customer have agreed to and is it being injected at the right dosage or do we need to adjust?” Guliuzo said.

Baker Hughes’ FORSA suite of solutions is a part of this line of thinking. The FORSA chemicals have been used in several operations both on and offshore.

In the Bakken/Three Forks, an operator experiencing scale problems used FORSA’s SCW8225 scale inhibitor to successfully treat more than 360 sucker rod lift wells in this field. The inhibitor was also used on the electrical submersible pumping (ESP) systems in this field. No scale-related failures on the sucker rod lift wells or the downhole ESP equipment was reported in the field during the more than four years of treatment with SCW8225 scale inhibitor, according to Baker Hughes.

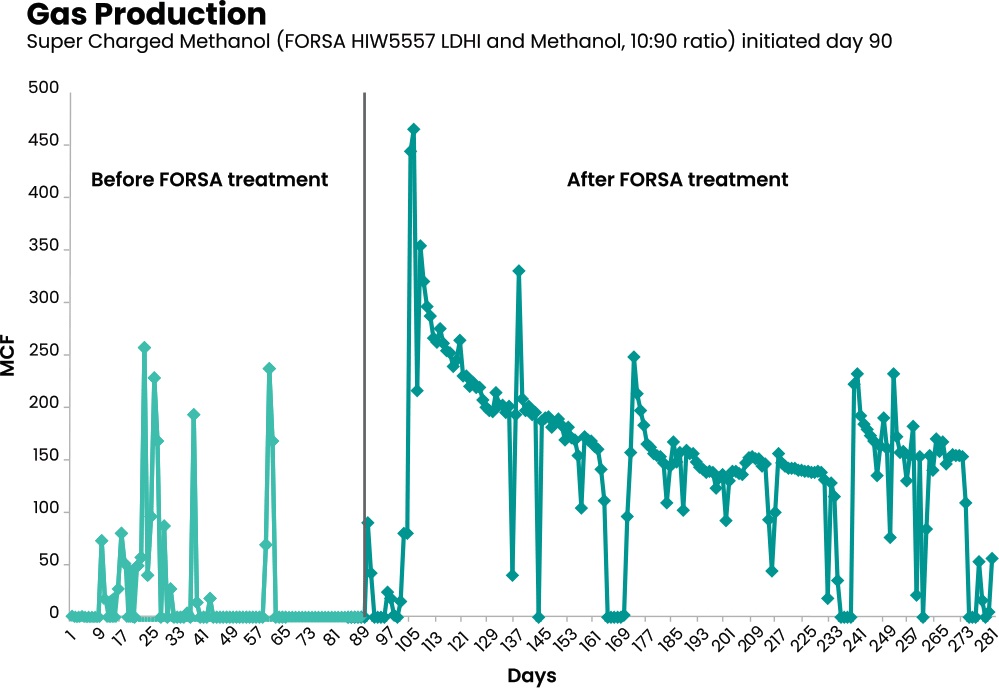

Baker Hughes also used FORSA in southwest Wyoming to assist an operator having hydrate issues. After various attempts at methanol injection failed to control the problem, resulting in high maintenance costs and poor production output, Baker Hughes assessed the problem and used its FORSA HIW5557 low-dosage hydrate inhibitor (LDHI) in conjunction with the methanol. This combination resulted in a super-charged methanol/LDHI that boosted production 530% and increased revenue by $20,000 per month, Baker Hughes said.

While the oil and gas industry is normally slow to adapt, these combination chemistries appear to herald an evolution in flow assurance, providing a more efficient and sometimes quicker solution. Lucente-Schultz said ChampionX aims to innovate in “a way that is necessary and to our customers and if we're going to provide the most value to our customers.”

Recommended Reading

Kissler: OPEC+ Likely to Buoy Crude Prices—At Least Somewhat

2024-03-18 - By keeping its voluntary production cuts, OPEC+ is sending a clear signal that oil prices need to be sustainable for both producers and consumers.

Canadian Natural Resources Boosting Production in Oil Sands

2024-03-04 - Canadian Natural Resources will increase its quarterly dividend following record production volumes in the quarter.

Buffett: ‘No Interest’ in Occidental Takeover, Praises 'Hallelujah!' Shale

2024-02-27 - Berkshire Hathaway’s Warren Buffett added that the U.S. electric power situation is “ominous.”

Aramco Reports Second Highest Net Income for 2023

2024-03-15 - The year-on-year decline was due to lower crude oil prices and volumes sold and lower refining and chemicals margins.

Moda Midstream II Receives Financial Commitment for Next Round of Development

2024-03-20 - Kingwood, Texas-based Moda Midstream II announced on March 20 that it received an equity commitment from EnCap Flatrock Midstream.