An otherwise learned young dot-com executive (there are still a few out there) told me recently that he was glad to discover that most of America's imported crude oil comes from Venezuela, not Saudi Arabia. "So," he said, "clearly our interest in Middle Eastern politics is not for its oil." If only that were true. (In 2001, the U.S. imported an average 1.7 million barrels of oil per day from Saudi Arabia and 1.5 million from Venezuela.) And, if only it were so simple. Editor Leslie Haines writes, on a preceding page, about Americans' sophomoric understanding of the oil industry. Sometimes it is just plain ignorance. A university professor I met a couple of years ago in Monterey, California, was not delighted to hear that I was in the area in advance of an IPAA meeting. She despised the oil industry, and said the Louisiana and eastern Texas coasts had dirty sand and dirty water because of offshore oil and gas drilling. She was sorry to hear that the far-from-pristine beaches and not-so-emerald water are the result of Mississippi River silt, which the Gulf of Mexico's current pushes westerly from the Mississippi's mouth. To explain how much silt the river dumps into the Gulf of Mexico, I showed her all the land that is south of New Orleans that wasn't there a few thousand years ago when the river flowed through what is now the Atchafalaya Basin. The build-up is so severe, the river wants to flow through the basin-the shorter route to the Gulf, again. "Well," she replied, "there is still some pollution from drilling offshore." Whatever. Some Floridians could learn this lesson too. Because of the same westerly current, the odds are extremely low of a spill offshore the Spinnaker beachfront patio in Panama City ever reaching the Florida coast. The current is made apparent by the military base on the western side of the entrance to Pensacola harbor: the fort is no longer there. It was washed away in less than 100 years of westerly erosion. Meanwhile, the one on the eastern side, Fort Pickens, which held Apache medicine man Geronimo at one time, has grown a few hundred yards on its western end. Essentially the entrance is about as wide as it ever was; it's just moved a few hundred yards left. Amy Myers Jaffe made the following point at a recent Houston energy luncheon: How could Florida tourists possible see offshore drilling platforms, which take hours to reach by helicopter? Jaffe is senior energy advisor and project coordinator for energy research at the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy at Rice University in Houston. Americans have the luxury of SUVs and opposing oil and gas drilling essentially anywhere it isn't already because of the Middle East. Not all of its oil comes here, but its existence helps assure the price we pay. H.E. Nabil Fahmy, Egypt's ambassador to the U.S., said at a Houston World Affairs Council program that there is nothing novel out there, in terms of ideas, for how to resolve the problem at home. Israel wants security; Palestine wants freedom. "Security cannot be a zero-sum game...Security for Israel will only be assured if there is freedom for Palestinians...Neither side can have peace if the other doesn't. Neither side can have security if the other doesn't." Would we be as involved in Middle Eastern politics, if it weren't for oil? It isn't likely. Would that be a good thing? Undoubtedly. Will we drive just 10 fewer miles a week to make the statement that we've had enough Middle Eastern politics and we're not going to be blamed for it anymore? Not likely. Will Californians? Surely it's not their problem. And in Florida? It's not their problem, either. For the record, the top foreign supplier of oil to the United States during 2001 was Canada (1.8 million barrels per day), according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. After Saudi Arabia (No. 2) and Venezuela (No. 3) was Mexico (1.4 million). Jaffe told a special Middle Eastern version of the story of the scorpion and turtle. The turtle agrees to give the scorpion a lift across a wadi after the scorpion insists it wouldn't sting the turtle because, after all, they would both die. Midway, the scorpion stings the turtle, who asks, "Why did you do that? Now we will both die." Usually the scorpion answers, "I'm a scorpion. It's what I do." In Jaffe's version, the scorpion answers, "This is the Middle East." I guess in an American version, the scorpion would say, "This is my backyard." -Nissa Darbonne, Managing Editor

Recommended Reading

Ithaca Deal ‘Ticks All the Boxes,’ Eni’s CFO Says

2024-04-26 - Eni’s deal to acquire Ithaca Energy marks a “strategic move to significantly strengthen its presence” on the U.K. Continental Shelf and “ticks all of the boxes” for the Italian energy company.

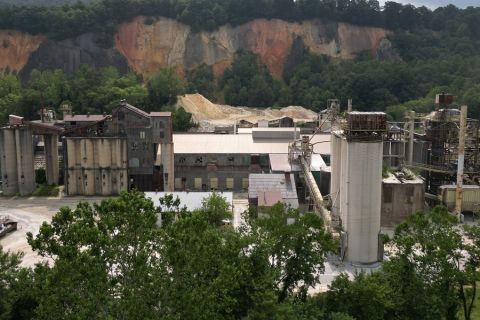

Apollo to Buy, Take Private U.S. Silica in $1.85B Deal

2024-04-26 - Apollo will purchase U.S. Silica Holdings at a time when service companies are responding to rampant E&P consolidation by conducting their own M&A.

Deep Well Services, CNX Launch JV AutoSep Technologies

2024-04-25 - AutoSep Technologies, a joint venture between Deep Well Services and CNX Resources, will provide automated conventional flowback operations to the oil and gas industry.

EQT Sees Clear Path to $5B in Potential Divestments

2024-04-24 - EQT Corp. executives said that an April deal with Equinor has been a catalyst for talks with potential buyers as the company looks to shed debt for its Equitrans Midstream acquisition.

Matador Hoards Dry Powder for Potential M&A, Adds Delaware Acreage

2024-04-24 - Delaware-focused E&P Matador Resources is growing oil production, expanding midstream capacity, keeping debt low and hunting for M&A opportunities.