To be clear, the problem with the language in parts of the federal Clean Water Act (CWA) has been a lack of clarity.

It goes like this: An oil and gas executive pondering a parcel of land asks what appears to be a simple question: Is it legal to operate here? But if that land is covered by the “Waters of the United States” (WOTUS) rule, the simple answer for many years has been: hmmm, good question.

In May, the Supreme Court (SCOTUS) put its stamp on the issue in a 9-0 ruling in Sackett v. Environmental Protection Agency that put to rest the uncertainty executives face in dealing with this particular law.

Except it didn’t, at least not yet. And, just so we’re clear, it might not—at least for a while.

The Clean Water Act, passed in 1972 and signed by President Richard Nixon, prohibits the discharge of pollutants into “navigable waters.” How regulators have enforced the law, however, has fluctuated through the years and through presidential administrations.

The definition of which waters were protected under the law was originally a very narrow one, Jonathan Brightbill, Washington-based partner at Winston & Strawn and chair of its environmental litigation and enforcement practice, told me.

Over time, however, it broadened considerably to where, in an opinion by Justice Antonin Scalia in Rapanos v. United States, the rule covered “virtually any parcel of land containing a channel or conduit … through which rainwater or drainage may occasionally or intermittently flow.”

In this era, with this court, it’s a regulation almost begging to be reined in.

“You have these Supreme Court decisions that said, ‘well, no, the statute doesn’t allow the regulation to be that broad,’” Brightbill said. “And you had this unusual circumstance where the regulation was out of sync with the Supreme Court precedent and the statute.”

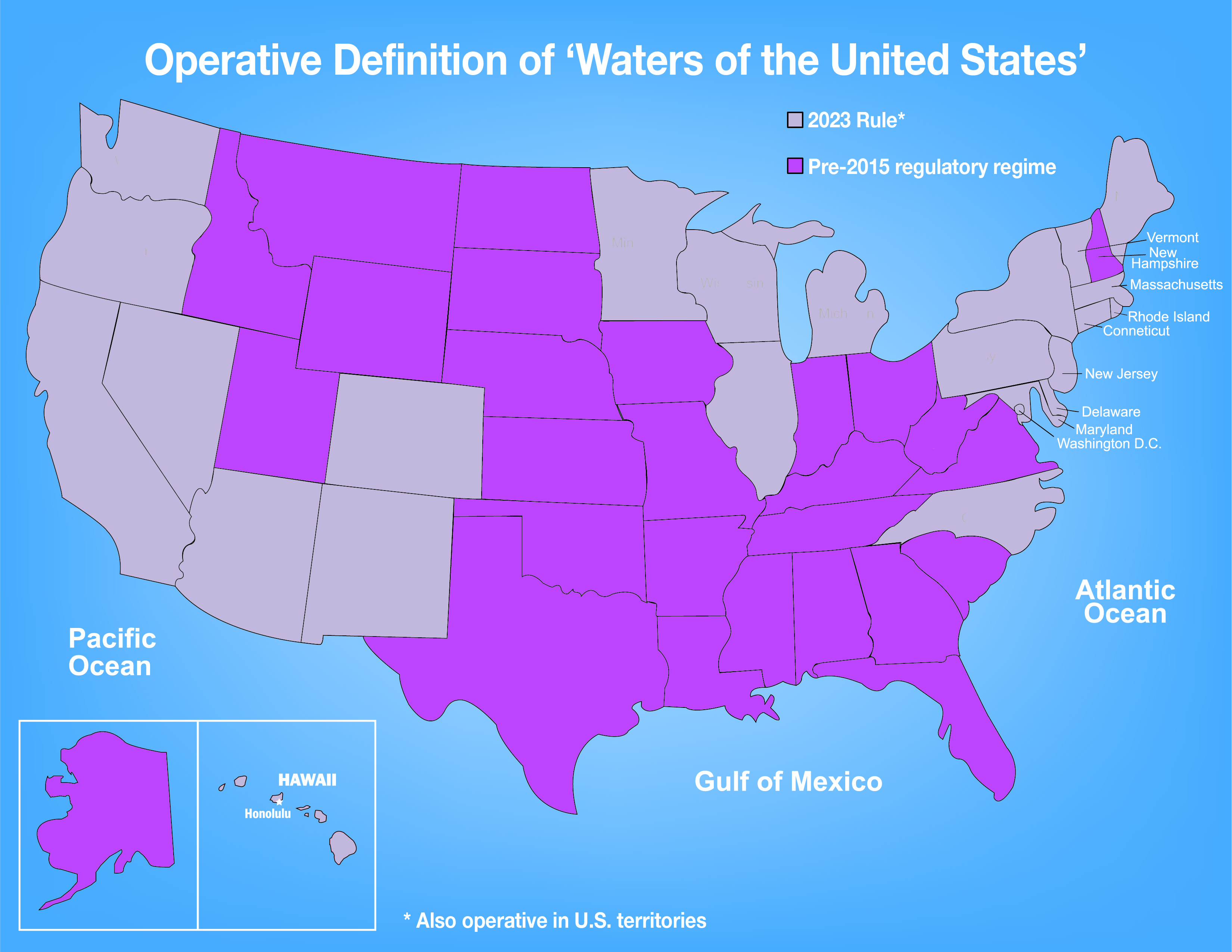

In 2015, the EPA under the Obama administration issued its WOTUS rule that expanded the definition beyond Supreme Court precedent. It was vacated by the courts and eventually repealed by the Trump administration. Trump’s EPA introduced the Navigable Waters Protection Rule, which streamlined the definition of WOTUS to exclude groundwater, storm water runoff, ditches and artificial lakes, among others.

The regulation fit within the limits of the Supreme Court’s rulings, Brightbill said. As acting assistant attorney general for the Environment & Natural Resources Division of the Department of Justice, he successfully defended it against preliminary injunctions in California courts and in appeals to the 10th Circuit in Denver.

The Trump-era rule was vacated in 2021 when the Biden Justice Department declined to defend it in a lawsuit. That led to the current WOTUS definition, which was published in January and took effect in March. It is not operative due to litigation.

What is water?

Which brings us to the Sackett case. In 2004, the EPA ordered the Sacketts to stop backfilling their property near Priest Lake in Idaho. The Sacketts wanted to build a house there, but the agency determined that the backfilling affected wetlands on their tract.

The Sacketts sued, contending the wetlands on their property, which is about 100 yards from the edge of the lake, do not constitute “waters of the United States.” They argued that their wetlands do not feed directly into navigable waters and are therefore not covered by the CWA. The EPA countered that they were covered because they are adjacent to waters that do feed the lake.

The opposing arguments in the Sackett decision reflect those that emerged in Rapanos, a 2006 case involving wetlands. Because its opinion represented a plurality, not a majority of the court, it did not set a precedent.

In Scalia’s plurality opinion, wetlands needed to have a “continuous surface connection” with navigable waters to be covered by CWA. In contrast, Justice Anthony Kennedy provided a “significant nexus” test in his opinion, meaning an adjacent wetland would be covered by the CWA if it had a significant effect on the water quality of navigable waters. The EPA enforced the law using Kennedy’s definition, which raises another question: What does “significant” mean?

“When you use words like that, you give federal agencies substantial discretion to come in and interpret what they mean,” Peter Whitfield, Washington-based partner at Sidley Austin, told me. “I believe it’s one of the reasons why this case ended up back before the Supreme Court.”

In the Sackett case, the court ruled the wetlands on their land are not “waters of the United States” because they lack a continuous surface connection with the lake. The majority opinion, written by Justice Samuel Alito, established precedent and is now law, Whitfield said.

Are we clear?

So, the Sacketts achieved clarity—they get to build their house. What about everybody else with an interest in the definition of WOTUS?

The EPA revised its rule in accordance with the Sackett decision and, in late July, sent it to the Office of Management and Budget for vetting. A public release of the new rule was promised by Sept. 1.

A SCOTUS decision and revised rule would seem to clear things up. But if a rule is issued in Washington, somebody is bound to hate it, and regulation begets litigation. Previous rules have been tied up in the courts, not to mention dumped by subsequent administrations.

Water quality is also not an exclusively federal domain. The CWA states that individual states have primary authority over land and water use, so various state regulations can hinder projects, as well.

But hey, if you want to celebrate the clarity that SCOTUS has bestowed upon plans for your new project, by all means, go for it. Just don’t assume you’re in the clear.

Recommended Reading

NOG Closes Utica Shale, Delaware Basin Acquisitions

2024-02-05 - Northern Oil and Gas’ Utica deal marks the entry of the non-op E&P in the shale play while it’s Delaware Basin acquisition extends its footprint in the Permian.

California Resources Corp., Aera Energy to Combine in $2.1B Merger

2024-02-07 - The announced combination between California Resources and Aera Energy comes one year after Exxon and Shell closed the sale of Aera to a German asset manager for $4 billion.

DXP Enterprises Buys Water Service Company Kappe Associates

2024-02-06 - DXP Enterprise’s purchase of Kappe, a water and wastewater company, adds scale to DXP’s national water management profile.

Pioneer Natural Resources Shareholders Approve $60B Exxon Merger

2024-02-07 - Pioneer Natural Resources shareholders voted at a special meeting to approve a merger with Exxon Mobil, although the deal remains under federal scrutiny.

Parker Wellbore, TDE Partner to ‘Revolutionize’ Well Drilling

2024-03-13 - Parker Wellbore and TDE are offering what they call the industry’s first downhole high power, high bandwidth data highway.