Writing the history of Hart Energy for this month’s 50th anniversary special edition, I learned more details about the 25 years preceding my joining the company in 1998. And it reminded me of the long conversations I’ve had the opportunity to have with the industry’s leaders.

They’ve patiently taken time to teach me about mudstones and mudlogs, sand-duning and sliding sleeves, volatile oil and dead oil, TOC (total organic content) and the toe.

And didn’t mind that I had to ask some questions that were embarrassingly daft.

A Bakken operator, describing the completion recipe in 2016 and the company’s overall success, said one of the ingredients was animal spirits. Yes, I had to ask: Were we talking Keynesian about the company’s success or do completions engineers call the brew “animal spirits?”

The miracle of renewed American energy independence is magical, after all.

Shale wildcatter Dick Stoneburner, talking about the Eagle Ford in 2013, called it a crummy rock. Or did he mean “crumby?” We laughed about that again just the other day.

North Dakota Bakken pioneer Harold Hamm suggested in an email in 2019 that I ask him about “IMO” in an onstage fireside chat at an upcoming Hart conference. “IMO” to me meant text code for “in my opinion.” Google suggested it might mean the annual International Mathematical Olympiad.

Hamm laughed, “No, I mean the International Maritime Organization.”

The energy industry has been generous, too, with teaching in the field itself. And the oil and gas field is beautiful.

Two months into joining Hart Energy, I was off to the Sahara Desert with Anadarko Petroleum, securities analysts and institutional investors. The sun set for hours at base camp in Hassi Messaoud, Algeria, during an outdoor buffet of paella, couscous, hummus, koshari, Méchoui, kebabs and salads.

In Hassi Berkine Field the next morning, a glimmering processing facility rose from the desert floor. A pair of camels without masters walked past. Departing later that day, the moon rose from behind the dunes to the east as the sun set behind dunes to the west. Georgia O’Keeffe would have liked it there.

On a trip to a coalbed-methane field in eastern Kansas, a first stop was in downtown Wichita where there are life-size statues on the sidewalks of ordinary people standing at street corners, playing hopscotch, walking a pony.

Oil and Gas Investor co-founder and Photo Editor Lowell Georgia snapped me interviewing one, a lady pointing at an apparently remarkable event in the skyline.

In the Gallup oil field in New Mexico, I was shown how to read ancient markings that operators take care to not disturb. In the hills of the Williston Basin, I was taught how to drive on ice.

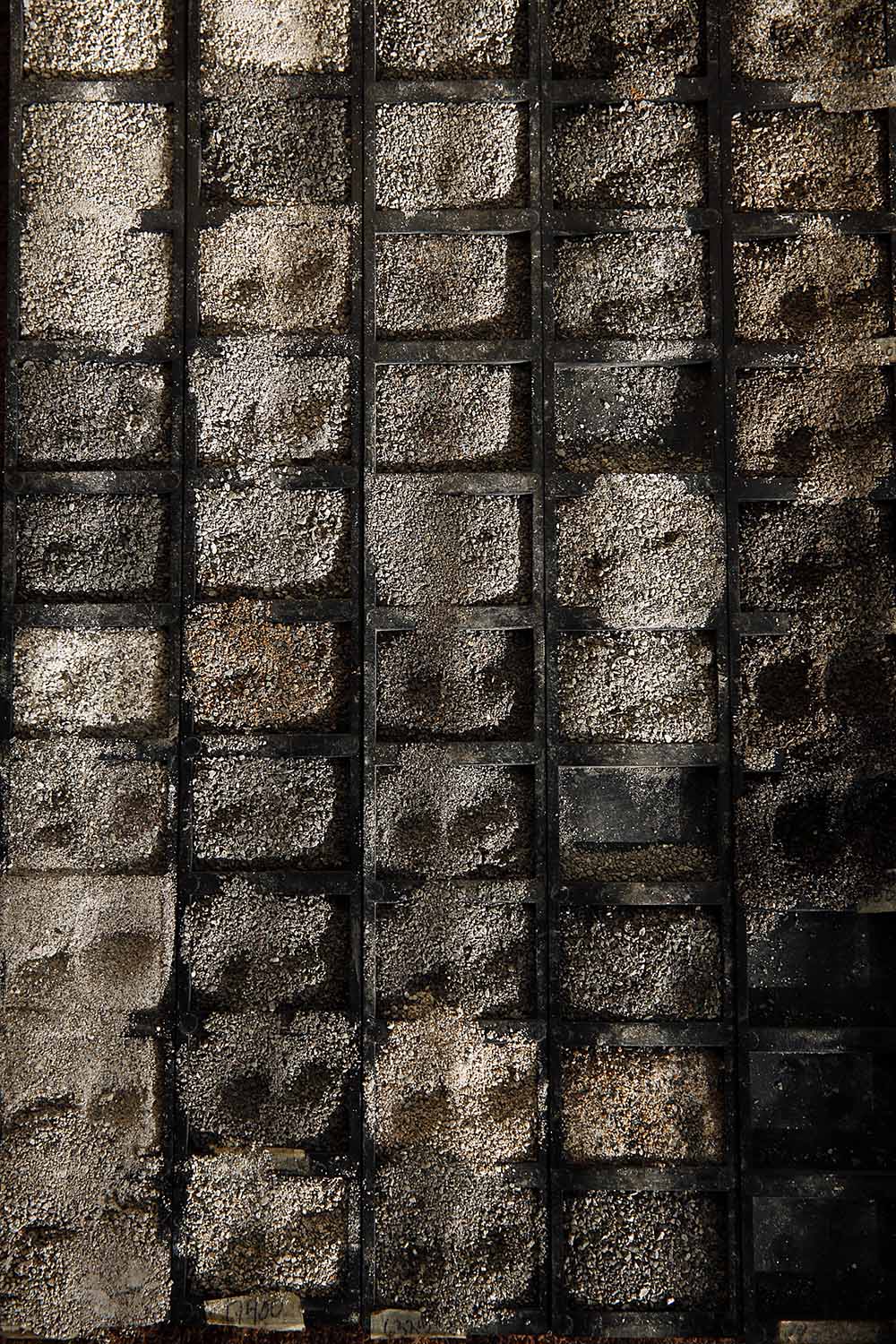

On a field trip with Newfield Exploration Co., now part of Ovintiv, to the Stack play in Oklahoma, a photo op appeared in the logger’s cabin: a tray of cuttings.

They were beautiful. All in the gray-charcoal-black color spectrum, the magazine’s freelance photographer, Tom Fox, understood my “suggestion” to photograph it: It was more important than what it may have appeared to him to be, which was 40 shades of gray.

He set it up next to the cabin’s one window, so the morning light would give it depth and texture. The image was selected for the January 2015 cover. I came upon it again recently, staring at it even longer than the first time, each particle revealing its secrets.

Cody Campbell, co-founder of Permian wildcatter Double Eagle, said in an on-stage interview this year, “Every acre has a story.” When I look at that tray of cuttings, I think every tray of cuttings tells a story, too.

The beauty of the oil and gas field, which I had witnessed growing up in in South Louisiana, is well known by more than a century of wildcatters and oilfield-service professionals. Hart Energy shared it with the world, beginning in 1981.

These same oil and gas professionals and thousands more who enter the industry each year continue today to make the beautiful possible—that is, mankind’s existence on Earth.

They incessantly encounter the hypocritical: “End fossil fuels but not my YouTube channel. And don’t forget to ‘like’ and ‘subscribe’—from your own hydrocarbon-based products.”

Four protesters glued their feet to the floor of the stands at the recent U.S. Open, disrupting play for 50 minutes while medical personnel dissolved the glue.

Toby Rice, president and CEO of EQT Corp., the No. 1 U.S. gas producer, was there. He said at an energy forum in Austin in September, “There’s no better statement of how hard it is to live in a world without fossil fuels when you can’t even protest fossil fuels without using fossil fuels.”

Recommended Reading

Shipping Traffic Freezes Up in Port Waters After Baltimore Bridge Collapse

2024-03-26 - U.S. port of Baltimore traffic was suspended until further notice following a bridge collapse. At least 13 vessels expected to load coal were anchored near the port at the time of the incident.

Segrist: The LNG Pause and a Big, Dumb Question

2024-04-25 - In trying to understand the White House’s decision to pause LNG export permits and wondering if it’s just a red herring, one big, dumb question must be asked.

Permian Gas Finds Another Way to Asia

2024-04-30 - A crop of Mexican LNG facilities in development will connect U.S. producers to high-demand markets while avoiding the Panama Canal.

CERAWeek: Trinidad Energy Minister on LNG Restructuring, Venezuelan Gas Supply

2024-03-28 - Stuart Young, Trinidad and Tobago’s Minister of Energy, discussed with Hart Energy at CERAWeek by S&P Global, the restructuring of Atlantic LNG, the geopolitical noise around inking deals with U.S.-sanctioned Venezuela and plans to source gas from Venezuela and Suriname.

Exclusive: Chevron Balancing Low Carbon Intensity, Global Oil, Gas Needs

2024-03-28 - Colin Parfitt, president of midstream at Chevron, discusses how the company continues to grow its traditional oil and gas business while focusing on growing its new energies production, in this Hart Energy Exclusive interview.