During this long hot summer, the fun begins. The U.S. gets to decide how it weighs a complex ratio of low-cost energy, lack of supply as demand grows, environmental safety, efficiency and job growth. Energy demand typically rises at about two-thirds the rate of a country's economic growth, according to Harry Longwell, head of Exxon Mobil's U.S. exploration and development group. The energy behemoth is itself like a small country-it recently surpassed General Motors to reach the top of the Fortune 500. It will end up with zero debt this year, even as it spends billions to buy back stock. Maybe it should acquire and restructure California? Speaking at a Houston conference last winter, Longwell said the energy industry faces tough challenges, especially as natural reservoir depletion runs about 2% annually in OPEC nations and 7% to 8% in non-OPEC countries. Required overall production growth thus approaches 80 million barrels a day between now and 2010, he said. Put another way, half of the oil supplies that will be required have not even been found yet. Unfortunately, consumers want it all now: cheaply, abundantly and with absolutely no environmental impact, and all before breakfast, he said. But not in their back yards. "Supplying energy in the amounts needed cannot be taken for granted," Longwell advised. "I wish I had a simple, valid estimate of what the future holds for this industry. Establishing the right political and financial framework [for increased and successful drilling] requires a lot of work on the part of companies and governments. We need a series of, in effect, bargains: 'We'll find it economically and environmentally, if you'll grant us access.'" To that end, at press time the Bush administration laid its first energy offer on the table. "I'll see your coal and raise you twice the natural gas, plus one nuke and a new pipeline...." No doubt Congress and the public will wrangle over their part of the bargain for the rest of this year. They will fiddle while Rome sweats. Meanwhile, gasoline and power will be no bargain. We note that the U.S. rig count recently reached a 15-year high, all due to gas seekers. The gas rig count has averaged 915 year-to-date versus 720 throughout 2000, up 49% this year. This accounts for the majority of the rig increase from last year-at least 300 of the 379 additional rigs running, according to investment firm A.G. Edwards. But all this drilling leads to what end? Salomon Smith Barney says 40 majors and leading independents replaced 153% of their gas production in 2000 through drilling and reserve revisions. What about this year? A.G. Edwards reports that first-quarter U.S. production went up, but by less than 2%, both year-over-year and since the prior quarter, for 27 E&P companies it follows (adjusted for acquisitions and divestitures). Petrie Parkman & Co. says production went up just 0.6% over first-quarter 2000 in the U.S. and 9.9% in Canada, for a blended rate of 1.5%. It is impossible to get accurate, complete and timely numbers. Data from the Energy Information Administration and state agencies usually differ from analysts or the companies themselves, or is less timely. UBS Warburg points out that any analysis is clouded by the impact of producers keeping their gas liquids in the production stream, because high gas prices rendered it uneconomic to strip out those liquids. Adjusting for this and for M&A activity, gas production fell 1.6% from the year-ago quarter, and 0.3% from the fourth quarter, the firm reports. "While there is tangible evidence of production growth, this first quarter's output data and gathering volumes indicate the response is surprisingly muted, given unprecedented levels of drilling," says a Petrie Parkman report. "We continue to believe...demand growth will outstrip a short-lived surge in supply...our expected average 2001 Nymex benchmark price remains $5.50 per Mcf." EOG Resources provides one example of a mostly gas-oriented company's response. Its first-quarter North American gas production rose 4.2% over the prior year's first quarter. To position for more growth, however, the Houston company is getting serious. It has increased its acreage holdings 50%, its geological and geophysical headcount by 20%, and the number of rigs drilling 50% compared with a year ago. That sounds like a strong bet on gas demand and prices. Here's an ironic twist: Last winter the CEO of an energy dot-com told reporters, "We want to become invisible, like electric power is. By that I mean you focus on developing oil and gas around the world, and we provide a mechanism to aid that, which is simple but invisible. It's like when you operate a mall, you create a venue for buyers and sellers, yet they don't know who owns the mall. Or, you flip a switch but you don't know where the electricity comes from." Since then, his investors have pulled the plug, shutting the company down and laying off all employees. And electric power, at least in California, is becoming invisible.

Recommended Reading

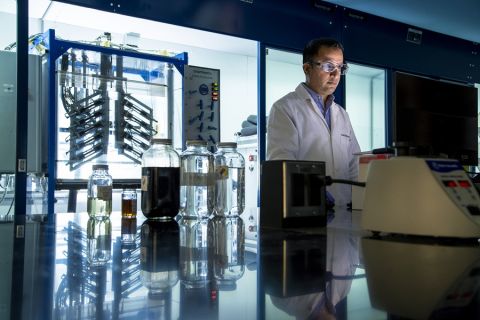

Defeating the ‘Four Horsemen’ of Flow Assurance

2024-04-18 - Service companies combine processes and techniques to mitigate the impact of paraffin, asphaltenes, hydrates and scale on production—and keep the cash flowing.

Tech Trends: AI Increasing Data Center Demand for Energy

2024-04-16 - In this month’s Tech Trends, new technologies equipped with artificial intelligence take the forefront, as they assist with safety and seismic fault detection. Also, independent contractor Stena Drilling begins upgrades for their Evolution drillship.

AVEVA: Immersive Tech, Augmented Reality and What’s New in the Cloud

2024-04-15 - Rob McGreevy, AVEVA’s chief product officer, talks about technology advancements that give employees on the job training without any of the risks.

Lift-off: How AI is Boosting Field and Employee Productivity

2024-04-12 - From data extraction to well optimization, the oil and gas industry embraces AI.

AI Poised to Break Out of its Oilfield Niche

2024-04-11 - At the AI in Oil & Gas Conference in Houston, experts talked up the benefits artificial intelligence can provide to the downstream, midstream and upstream sectors, while assuring the audience humans will still run the show.