In a tree-lift, a crane operator maneuvers equipment at LLOG Exploration’s Delta House platform. Delta House is designed as a hub for future subsea tiebacks in the GoM’s Mississippi Canyon. (Source: LLOG Exploration Co. LLC)

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the July 2019 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

For more than a century, the Law of the Sea has required the master of a ship to render assistance to seafarers in danger of being lost.

No such duty is owed to industry. In 2015, as oil prices plunged, U.S. Gulf of Mexico (GOM) oil and gas operators might have remained adrift.

But, in a twist, they faced their distress by heading deeper, faster and farther out into the sea. And, most importantly, they did it for less money.

Talos Energy Inc.’s history in the GOM includes two decades of strong performance, said Timothy S. Duncan, president and CEO.

“The attractiveness of the basin and the spectrum of what’s possible here are something we know very well,” Duncan told Oil and Gas Investor.

While no one is ready to say that the GOM is experiencing a renaissance, there are clear signs that the Gulf has got its groove back. Companies have stepped up exploration activity, aggressively pursued lease sales and transacted on billions of dollars in deals.

Many company leaders said they’re approaching 2019 and beyond with robust drilling plans.

Fieldwood Energy LLC CEO Matt McCarroll said the company is launching plans for $450 million of capital spending in the U.S. GOM and offshore Mexico with first production in late 2020 or early 2021. The capex is more than Fieldwood has spent, combined, since the downturn.

“Four to six wells a year is probably the pace we’ll be looking at,” McCarroll told Investor. “Costs have come down substantially, depending on depth of the well. We are drilling, completing and tying back wells this year for right at $100 million each.”

The shift in capital and the natural attrition from the commodity price crisis left fewer operators but a “significant amount of remaining opportunity,” Duncan said.

In the U.S. deep water, Talos has plans for two subsea hook-up projects and two new drills, all in proximity to existing infrastructure, he said. The company expects capex to range between $465 million and $485 million in 2019.

“We will have an additional three to five wells in U.S. shallow water, again, drilled from existing infrastructure,” he said. “A key feature of our drilling program is that it is self-funded through our operations. We expect to be free-cash-flow positive after debt maintenance for 2019, as we were for 2018.”

attractiveness

of the basin and

the spectrum

of what’s

possible here are

something we

know very well,”

said Timothy S.

Duncan, president

and CEO of Talos

Energy Inc.

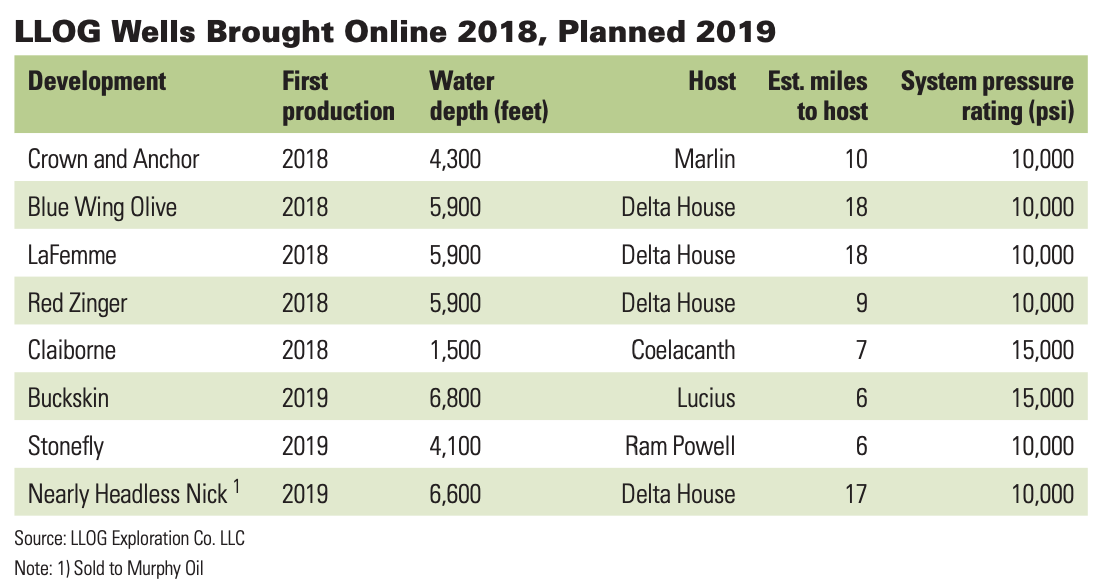

LLOG Exploration Co. LLC typically drills three to four exploratory wells per year, COO Rick Fowler said.

“Occasionally, when there is a large amount of development work to do, we will drill fewer exploration wells, and vice-versa,” he said.

On April 29, LLOG also entered into an agreement with Repsol E&P USA Inc. to exchange assets and jointly participate in Repsol’s Leon discovery and LLOG’s Moccasin discovery, both in Keathley Canyon blocks.

Michael Murphy, a research analyst with Wood Mackenzie’s GOM team, said private and independent GOM companies clearly have a lot to keep them busy.

“The Gulf of Mexico is coming alive again,” he said. “We’ve seen an uptick in activity in 2018. We’re expecting an uptick in exploration activity this year in 2019.”

Deepwater production has increased to the point of record production, while at the same time capex across the region has come down substantially since the heydays of $100 oil, he said.

“Operators have really hunkered down. They’ve found ways to commercialize. They’ve found ways to do more with less.”

Like their counterparts on the land, GOM operators have also optimized drilling to become more efficient. GOM operators employ modular platforms, simplified subsea field designs, and they enjoy the advantage of slightly higher Brent oil prices.

“The No. 1 thing of the year is small, quick turnaround subsea tiebacks,” Murphy said.

Speed Freaks

GOM operators can seem nearly prescient in their operations as they capitalize on their knowledge of where to drill and how fast. But they have superior skill when it comes to ordering equipment when it absolutely, positively has to be there in 18 months.

Subsea equipment allows operators to tie back new wells to floating existing production storage and offloading platforms using subsea flow lines. Operators save both money and time that would otherwise be spent building costly new platforms.

Talos has rapidly commercialized wells using tiebacks, including its Mount Providence subsea tieback that began producing within 18 months—about 60 days earlier than scheduled.

“This is one of Talos’s key strategies in the U.S. GOM and something we’re actively doing right now through our drilling program,” Duncan said. “The ability to bring on high-margin barrels through existing infrastructure, even before accounting for the positive differentials to WTI and high oil ratio, we believe provides our inventory of near-field tieback opportunities some of the most compelling economics in the industry.”

To accommodate subsea wells, Murphy said that GOM operators often order long-lead time items far in advance, and “we’ve even heard they’ll order this stuff before the well is even spud,” he said.

McCarroll said in May that Fieldwood had already placed orders for four subsea kits—equipment such as subsea trees, umbilical lines, other submersible technology--that it knows it will need. Subsea manufacturing companies have been signaling that orders have risen to their highest point in five years due to renewed demand, he said.

“Now is a good time to get in line [and] start building these kits,” McCarroll said. “We needed four or five of them, but what we did is we said we’re going to standardize the design.”

Fieldwood arranged for two subsea equipment designs that can operate in conditions at 10,000 PSI and another set of equipment for 15,000 PSI.

Fieldwood plans to bring production online within 12 to 18 months of drilling and orders ahead to accommodate a similar lead time for the equipment it will need. The Houston company targets lower-risk wells that it ties back to existing infrastructure it owns and operates, up to 25 miles away.

“If you wait until after you drill the well, it’s going to take you much longer to get on production,” he said. “We made the decision strategically to go ahead and start ordering these things, feeling very confident we’re going to be able to use them.”

Because the equipment is largely interchangeable, if Fieldwood doesn’t deploy equipment now it can use them for other wells.

Worst case scenario, McCarroll adds, “we can always sell them.”

LLOG’s approach relies on the use of standardized system designs and streamlined internal processes to reduce cost and development time.

“They’ve found ways to simplify design,” Murphy said. “They’re more comfortable with a field design that they’re almost able to engineer once and deploy multiple times.”

In 2015, for instance, LLOG brought its floating production system online in the Mississippi Canyon, capping a “very impressive” journey from an exploration well to producing facility in three years.

LLOG’s streamlined internal processes “allow us to move quickly from discovery to project sanction. We do not have a multiple stage gate approval process like many deepwater companies,” Fowler said. The company skips a preliminary FEED phase and doesn’t custom design every project.

“LLOG can generally order long lead equipment immediately following a discovery,” Fowler said. “Because of our alliance with TechnipFMC on all subsea equipment, we also avoid the time required for a bidding process on these long lead items.”

Talos focuses closely on cycle time, particularly for lower-risk projects.

In addition to collaborating with suppliers and partners, the company tries to utilize standardized equipment where possible.

“Of course, the most important element in reducing time to production is the availability of infrastructure, hence our focus on conducting exploration and exploitation drilling nearby facilities to which we have access and can quickly bring in new production,” Duncan said.

That’s increasingly important for GOM operators that are working to reduce cycle times—the duration from discovery to first production. It’s a key ingredient in keeping operators’ costs down and to reinvest.

‘No New Steel’

Shortening the cycle time of projects has become such good business that major oil companies are using similar methods.

Large companies are pairing with smaller, more agile private companies and independents, as well. Chevron Corp. and Fieldwood, for instance, are working together on a couple of prospects. The two companies already jointly own acreage and partnered in the March Bureau for Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) sale.

Fieldwood Energy

LLC CEO, said

that for all the

attention paid

on onshore shale

breakevens,

“from an internal

perspective, I

don’t really care.

All we do is the

Gulf of Mexico.

We feel like our

economics are

very compelling.”

McCarroll said major oil companies have seen the success that Fieldwood, LLOG, Talos and other companies have had in bringing smaller fields online efficiently, quickly and profitably.

Fieldwood and Chevron partnered to make bids on leases during the March lease sale. Wood Mackenzie noted that larger companies, including Equinor ASA, BP Plc and EcoPetrol, also partnered with smaller companies, demonstrating a shrinking pool of partners but an increased interest in working with more nimble operators.

“Chevron is looking at prospects that they would have never looked at before because they would have been too small,” McCarroll said, adding that he recently heard one Chevron executive say they want prospects “that don’t require new steel—that they don’t have to build new infrastructure for.”

The benefit of moving rapidly from discovery to production is that revenue can be reinvested more quickly in the next well, McCarroll said.

“It’s not crucial but it’s certainly very beneficial,” he said. “The economics would still be good if it took an extra six to 12 months or even more. But for a company our size, the ability to invest that cash and then recycle it [and] get the cash back quickly to be able invest in other wells is very important,” he said.

A well that costs $100 million to drill and tie back that also takes an extra year to bring on production could mean a delay of up to $50 million in cash flow “that I don’t get that I could use to reinvest in other wells,” he said. “So for our strategy, the quick cycle times are very important.”

Shale Shape

GOM operators aren’t blind to the fawning attention—and money—that onshore shale projects have commanded during the past several years.

But they are also confident that investor sentiment favoring free-cash-flow positive companies benefits them. And while they may not have the sheer number of transactions as onshore shale, M&A is picking up.

“It’s clear that for several years there has been an enormous amount of attention and focus on the onshore shale plays, not only from investors but from talented management teams,” Duncan said. “That shift in capital and the natural attrition that occurs during a commodity crisis have left fewer operators in the U.S. GOM, but with what we believe is a significant amount of remaining opportunity.”

continues to

become more

efficient. At

LLOG, our typical

breakeven price

for our projects

is under $30 per

boe,” said LLOG

Exploration Co.

LLC COO Rick

Fowler.

Wood Mackenzie noted that some GOM operators, such as Murphy Oil Corp., already straddle the offshore/shale divide. Murphy operates assets in North America, including the Eagle Ford Shale. Other companies, such as Kosmos Energy have evaluated shale but “decided offshore is where they prefer to be,” Murphy said.

“The Gulf of Mexico isn’t just competing with the Permian,” Murphy added. “It has to compete with Brazil and Mexico as well. So, the pressure is certainly there from different facets to make sure they can be competitive.”

LLOG focuses exclusively in the deepwater GOM.

“Our industry continues to become more efficient,” Fowler said. “At LLOG, our typical breakeven price for our projects is under $30 per boe [barrels of oil equivalent].”

While other operators may measure themselves against onshore plays, McCarroll is more direct.

“From an internal perspective, I don’t really care,” he said. “All we do is the Gulf of Mexico. We feel like our economics are very compelling.”

But in the crowded competition among E&Ps for capital, McCarroll understands that Fieldwood’s economics need to stand out.

The company’s F&D costs are less than $10 per barrel (bbl) and, in some cases, less than $6/bbl. Wells come on at high-flow rates with lease operating expenses of less than $10/bbl that are then tied to existing infrastructure.

With expenses tamped down and tiebacks to existing infrastructure saving more money, McCarroll said, Fieldwood’s breakeven costs are less than $20/bbl.

“And we’re not in the business to break even,” he said. “These economics are compelling.”

Robust operational activity and a hot streak for GOM M&A and operations reflect, for Duncan, “new and past investors realizing the potential of the Gulf and more generally, offshore conventional oil and gas as a free-cash-flow positive, value-generating business model that is sustainable over the long run.”

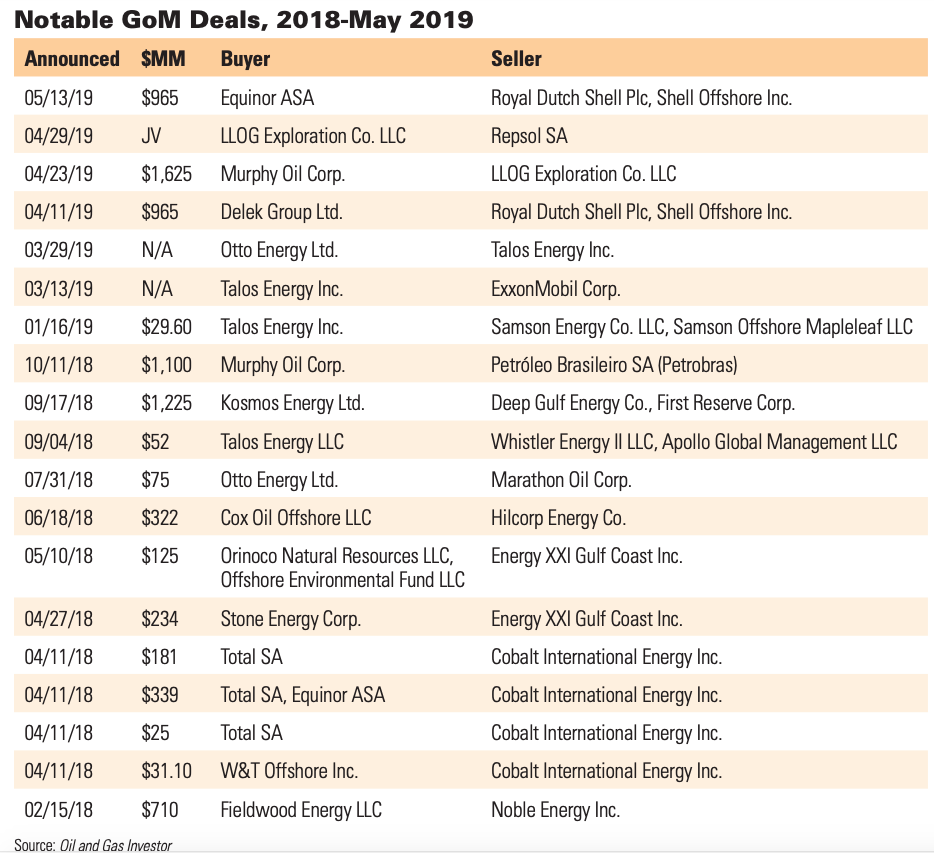

While onshore A&D has been hit or miss, the GOM continues to have a hot hand. Excluding joint ventures, deals by Equinor, Murphy, Delek Group Ltd. and others have tallied $3.6 billion so far in 2019. Last year, publicly announced deals totaled $4.4 billion.

In April, LLOG sold producing assets to Murphy Oil for up to $1.6 billion after Murphy exited from its offshore Malaysia position for about $2 billion in cash. The assets were a joint venture between LLOG Bluewater and Blackstone Group LP.

McCarroll said he liked Murphy’s deal and would have bought the assets himself had Fieldwood been able to deploy the cash as rapidly as Murphy.

“We look at acquisitions all the time. I’d like to think we see every acquisition that comes around in the Gulf of Mexico,” he said. “We’ve done a number of small, what I call bolt-on acquisitions, where we’ve bought out existing partners in fields or in wells that we wanted to consolidate or grow that interest.”

McCarroll said he thinks the consolidation opportunities are still very real today.

Echoing comments he made on Fox Business in May, McCarroll told Investor that the “Gulf of Mexico is the most misunderstood, underappreciated and underinvested basin in the world.”

McCarroll also said that scrutiny of Occidental Petroleum Corp.’s successful $38 billion bid for Anadarko Petroleum Corp., of the Fieldwood’s partners, focused too much on its Permian assets. Anadarko is one of the largest producers in the GOM and operates 10 facilities.

“The Anadarko Gulf of Mexico assets, while not getting near the publicity as the Permian Basin or the east Africa LNG, are the hidden jewel of that transaction,” McCarroll said, adding that Anadarko was the high bidder on more than two dozen GOM blocks in a March lease sale.

“We participated in some of the lease sales, going after some of those blocks,” he said. “I think it’s a good time to be in the Gulf of Mexico.”

Acquiring Targets

The U.S. GOM is massive, covering an area of about 160 million acres. It is also ancient, formed as the supercontinent Pangea began to break apart long ago.

The resulting GOM basin was flooded by seawater from the Pacific and Atlantic oceans basin, where the water it evaporated, leaving behind deposits of salt more than two-and-a-half miles deep.

Mexico is coming

alive again. We’ve

seen an uptick in

activity in 2018.

We’re expecting

an uptick in

exploration

activity this year

in 2019,” said

Michael Murphy,

a research analyst

with Wood

Mackenzie’s Gulf

of Mexico team.

Recent typography maps of the sea floor reveal salt domes, dunes and canyons warped and folded by salt and time.

Roughly 150 million years later, the GoM is still keeping secrets.

In April, Royal Dutch Shell Plc announced the Blacktip discovery—400 net feet of oil pay in about 6,200 feet of water. The discovery was made in the Wilcox Trend in the Alaminos Canyon, about 30 miles from the company’s Perdido platform.

“The Gulf … keeps on surprising us,” Martin Stauble, Shell’s vice president of exploration for North America and Brazil, said in May at Offshore Technology Conference 2019.

He noted that the company’s Mars development has been drilled for decades but is still being exploited. “We can drill deeper. We come up with new concepts,” he said.

As explorers, the operators of the GOM continue to push into new and old areas. On May 14, French geoscience firm CGG also said it would commence its first multiclient ocean bottom node survey in the GOM, to provide new detailed imaging of geologically complex structures in the Mississippi Canyon.

LLOG’s own seismic acquisition and reprocessing technology has enabled it to reduce risk, Fowler said. “As a result, our exploration success rate is around 70%,” he said.

LLOG has amassed a solid inventory of more 40 exploration prospects, primarily through lease sales, during the past several years.

LLOG’s transaction with Murphy sold 60% of the company’s current production but “0% of LLOG’s exploration prospects,” Fowler said.

“As a result, LLOG will have opportunities for many years to come,” he said.

At Leon, in LLOG’s Buckskin area, the company plans to drill adelineation well later this year as part of its partnership with Repsol.

“We believe Leon and Moccasin could be of adequate size to justify a second hub in the area,” Fowler said.

Talos is also participating with an EnVen Corp. subsidiary to drill the Green Canyon 21 Bulleit prospect in its Green Canyon core area. Talos plans to complete the well and tie it back to the Talos-owned and operated Green Canyon 18 facility about 10 miles away, the company said in March.

RELATED:

EnVen Files Drilling Plan For Green Canyon Blocks 723 and 767

Buckskin Boosts LLOG’s 2019 Startups In Deepwater GOM

Many GOM operators, such as Fieldwood, are targeting reservoirs in the lower and subsalt Miocene, which were formed about 23- to 65 million years ago.

Fieldwood is active in the Mississippi Canyon area, roughly 60 miles off the coast of Louisiana. More recently it drilled two wells in Green Canyon, roughly 160 miles south of New Orleans, where well water depths range from 3,400 feet to more than 7,000 feet.

McCarroll said the new wells, which were tied back to Fieldwood’s Bullwinkle platform, were significant. McCarroll’s Dynamic Offshore bought Bullwinkle from Shell in 2010. At the time, the goal was to keep the field economic through 2017.

While Fieldwood has drilled wells near Bullwinkle in the past, its two new Green Canyon tiebacks will extend the life of the field by another 15 to 20 years.

Fieldwood also has what McCarroll said he believes to be a “very, very competitive position” in the deeper Norphlet geological play. Shell has announced multiple discoveries in the area.

Fieldwood’s next big project on the Noble Energy Inc. assets it acquired last year will be the Katmai discovery, which Noble initially said had a potential of more than 60 million barrels of oil equivalent. The find was made 22 miles southeast of Fieldwood’s Tarantula production platform. Fieldwood acquired it and the Neptune platform from Noble.

McCarroll said Fieldwood will begin drilling wells in the second half of 2019 with hopes to have a well online by early 2020. Pipeline and umbilical infrastructure is currently being built and will be installed later this year.

“The Noble assets have really exceeded our expectations,” he said.

More importantly to McCarroll, the company’s offshore team has come together well after a year.

“I love what they’re doing,” he said.

Darren Barbee can be reached at dbarbee@hartenergy.com.

Recommended Reading

BP’s Kate Thomson Promoted to CFO, Joins Board

2024-02-05 - Before becoming BP’s interim CFO in September 2023, Kate Thomson served as senior vice president of finance for production and operations.

Magnolia Oil & Gas Hikes Quarterly Cash Dividend by 13%

2024-02-05 - Magnolia’s dividend will rise 13% to $0.13 per share, the company said.

TPG Adds Lebovitz as Head of Infrastructure for Climate Investing Platform

2024-02-07 - TPG Rise Climate was launched in 2021 to make investments across asset classes in climate solutions globally.

Air Products Sees $15B Hydrogen, Energy Transition Project Backlog

2024-02-07 - Pennsylvania-headquartered Air Products has eight hydrogen projects underway and is targeting an IRR of more than 10%.

HighPeak Energy Authorizes First Share Buyback Since Founding

2024-02-06 - Along with a $75 million share repurchase program, Midland Basin operator HighPeak Energy’s board also increased its quarterly dividend.