(Source: Shutterstock.com)

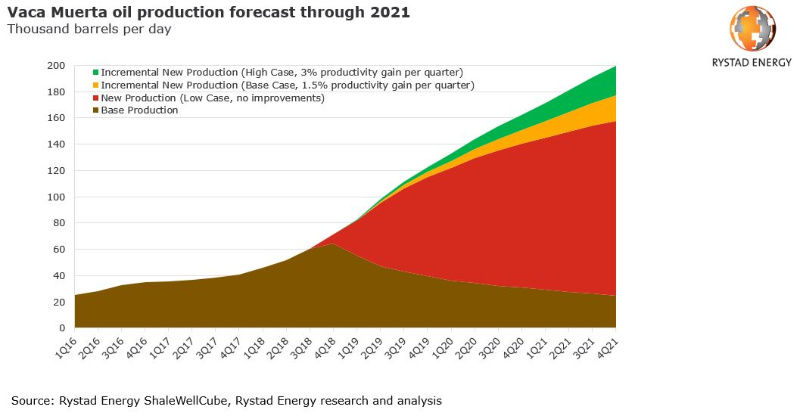

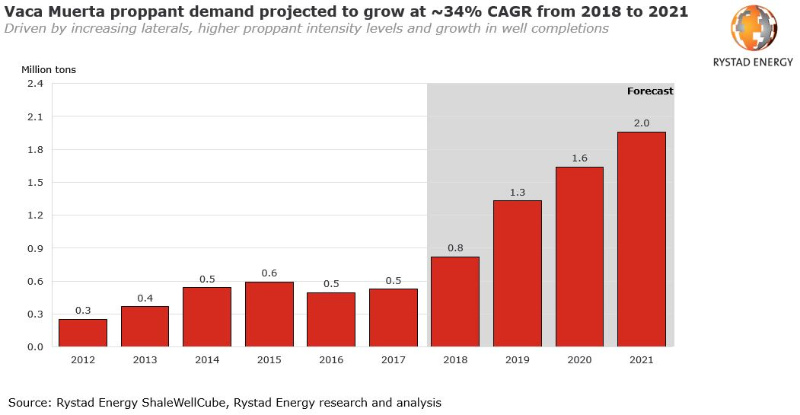

HOUSTON—Economic woes and political uncertainty could further impede growth of Argentina’s promising Vaca Muerta Shale, but the biggest bottleneck may be something with a more direct impact: proppant.

That’s according to a Rystad Energy analyst who spoke Sept. 18 at the Gastech Exhibition & Conference.

“We think this is the biggest bottleneck that prevents the Vaca Muerta from growing at that same exponential curve that we saw in a lot of the U.S. plays,” said Ryan Carbrey, senior vice president for global market intelligence for Rystad Energy. “You can’t really get proppant into the play very quickly. You have to truck it in from 600 or a thousand kilometers.”

Argentina has one of the largest shale oil and gas reserves in the world. Carbrey described rock in the Vaca Muerta as “just as good or better than comparable U.S. plays”—oilier parts being similar to the Permian Basin and gas similar to the Haynesville and Marcellus.

The formation, located in the Neuquén Basin, has technically recoverable resources of 308 trillion cubic feet of natural gas and 16 billion barrels of oil and condensate, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

By December 2018, more than 1 billion cubic feet per day of gas had been produced from the Vaca Muerta, which accounts for about a quarter of Argentina’s total gas production, the EIA said. But less than 5% of its acreage has entered the development phase.

Its potential has attracted South American companies such as YPF SA and Tecpetrol SA, which started buying sand from the Parana River to frack for gas in the Vaca Muerta, Bloomberg reported earlier this year. It also has attracted international majors such as Chevron Corp., Exxon Mobil Corp. and Royal Dutch Shell Plc.

Sand remains a crucial piece of the hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling mix needed to move shale development forward as witnessed in the U.S. shale plays like the Permian Basin.

With thousands of tons being used per well, demand has increased considerably, Carbrey said, adding it has reached about 1.3 million tons. That still pales in comparison to the 115 million tons, he said, is used in the U.S.

YPF and some local universities looked for quality sand sources closer to drilling sites about three to five years ago, he said, to no avail.

“From what we know they drilled over 3,000 kind of pilots sand wells to look for sand under the earth and they weren’t able to find anything super close,” Carbrey said. “I know there is quite a few companies still looking for sand in the area but right now again [they are] still needing to truck.” In addition to the distance, he said the roads are not great.

“The quality of the sand is also lower than the kind of similar used sands here in the U.S.,” Carbrey added. “The formations have higher pressures and lower quality sand could potentially be a problem.”

Other potential bottlenecks include infrastructure, macroeconomic factors, labor and pressure pumping, he said. There are about 35 companies providing pressure pumping services in the U.S., compared to six in Argentina, he said, adding there is “not a lot of horsepower.” In the field, Rystad is hearing from service companies who say they are feeling cost pressure, which “makes them not as excited to grow their fleets currently,” Carbrey said.

In early September, Halliburton Co. CEO Jeffrey Miller said “political and fiscal headwinds in Argentina” are among the conditions restraining its improved quarterly outlook, Reuters reported, noting the company opened Argentina’s first sand storage and loading facility in 2014.

RELATED: Political Turmoil, Price Freeze Cast Shadow On Argentina’s Vaca Muerta

“If these bottlenecks were able to be resolved which will take time, of course…there’s no reason we couldn’t see that same ramp-up in Argentina” as in the U.S., Miller added. “However, we’re not really expecting that in the near term.”

But progress is being made, albeit slowly, according to Carbrey.

“Both drilling and completion has seen over 30% growth this past year. Even through the downturn while there was a shift from more vertical drilling and completions to horizontal, horizontals increased,” he said.

Lateral lengths are also increasing, moving more toward two-mile laterals. Carbrey described the Vaca Muerta’s target zone as very thick—1,000 to 1,500 ft.

Several companies are moving forward with plans in Vaca Muerta, despite challenges.

Exxon Mobil, for example, said in June it is proceeding with oil development in the Bajo del Choique-La Invernada block, where it aims to produce up to 55,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day (boe/d) within five years. The project includes completing 90 wells, a central production facility and export infrastructure.

Shell announced in late 2018 its move to the development phase in the Sierras Blancas, Cruz de Lorena and Coirón Amargo Sur Oeste blocks, an area the company says has the potential to deliver more than 70,000 boe/d by the mid-2020s.

Recommended Reading

2023-2025 Subsea Tieback Round-Up

2024-02-06 - Here's a look at subsea tieback projects across the globe. The first in a two-part series, this report highlights some of the subsea tiebacks scheduled to be online by 2025.

TGS, SLB to Conduct Engagement Phase 5 in GoM

2024-02-05 - TGS and SLB’s seventh program within the joint venture involves the acquisition of 157 Outer Continental Shelf blocks.

StimStixx, Hunting Titan Partner on Well Perforation, Acidizing

2024-02-07 - The strategic partnership between StimStixx Technologies and Hunting Titan will increase well treatments and reduce costs, the companies said.

Tech Trends: QYSEA’s Artificially Intelligent Underwater Additions

2024-02-13 - Using their AI underwater image filtering algorithm, the QYSEA AI Diver Tracking allows the FIFISH ROV to identify a diver's movements and conducts real-time automatic analysis.

Subsea Tieback Round-Up, 2026 and Beyond

2024-02-13 - The second in a two-part series, this report on subsea tiebacks looks at some of the projects around the world scheduled to come online in 2026 or later.