Argentina’s famed Vaca Muerta shale formation, translated as “dead cow,” is arguably the most prospective outside the U.S., representing a game-changing opportunity to convert the country into a major exporter of piped-gas and oil to the Southern Cone region as well as oil and LNG to world markets.

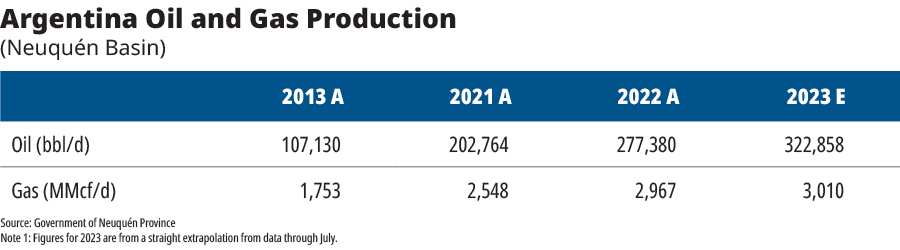

In recent years, production gains in Argentina have been impressive, driven primarily by higher production from the Vaca Muerta in Argentina’s Neuquén Basin. Further gains hold potential to drastically change the country’s energy matrix and help the country achieve energy self-sufficiency. That’s if Argentina can overcome the numerous above ground headwinds linked to economics, finance and infrastructure, all tied to political uncertainties. Whether newly elected president Javier Milei, an economist with two masters on the topic, can change any of that, remains to be seen.

Developments related to the Vaca Muerta have been massive. Without production contributions from the formation, Argentina’s oil production would be about half of what it is, while gas production would be about one-third of what it is, Argentina’s Neuquén Province Energy Minister Alejandro Rodrigo Monteiro told Hart Energy during a phone interview on Nov. 29.

Monteiro said without development of the Vaca Muerta in 2023, Argentina would have imported hydrocarbons and energy worth over $20 billion.

“In addition to the currency problem, [Argentina] would have had less than $20 billion, and by not having currency, the country couldn’t have acquired these hydrocarbons and energy. In other words, the country would have serious energy supply problems, in addition to problems related to reserves in Argentina’s Central Bank,” Monteiro said. “So, the Vaca Muerta’s development can be seen through all the energy that we stop importing, and also in the volume of energy that we can export and the dollars that this generates for the country.”

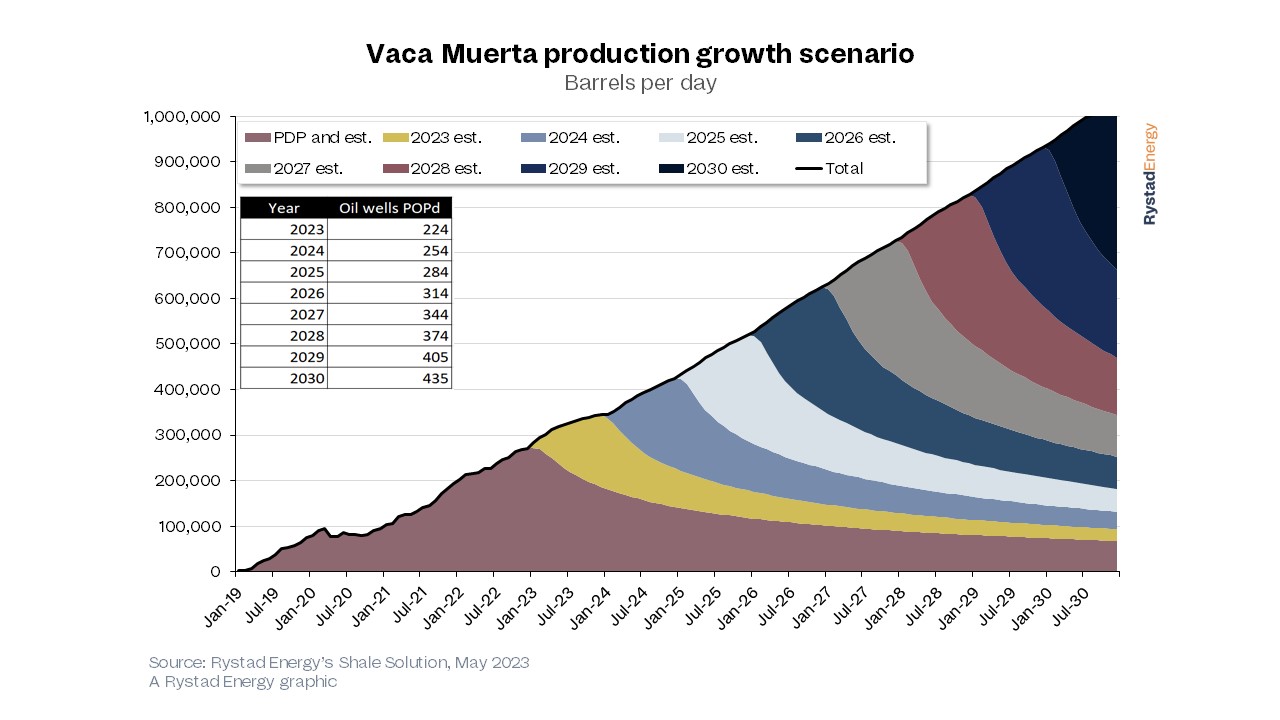

Monteiro reiterated that production from the Vaca Muerta could surpass 1 MMbbl/d by 2030 under a moderate growth scenario compared to around 323,000 bbl/d foreseeable in 2023, according to extrapolated production data through July from the government of the Neuquén Province. Through July, the Vaca Muerta contributed around 51% of Argentina’s total oil production profile and around 65% of its total gas production, according to provincial data.

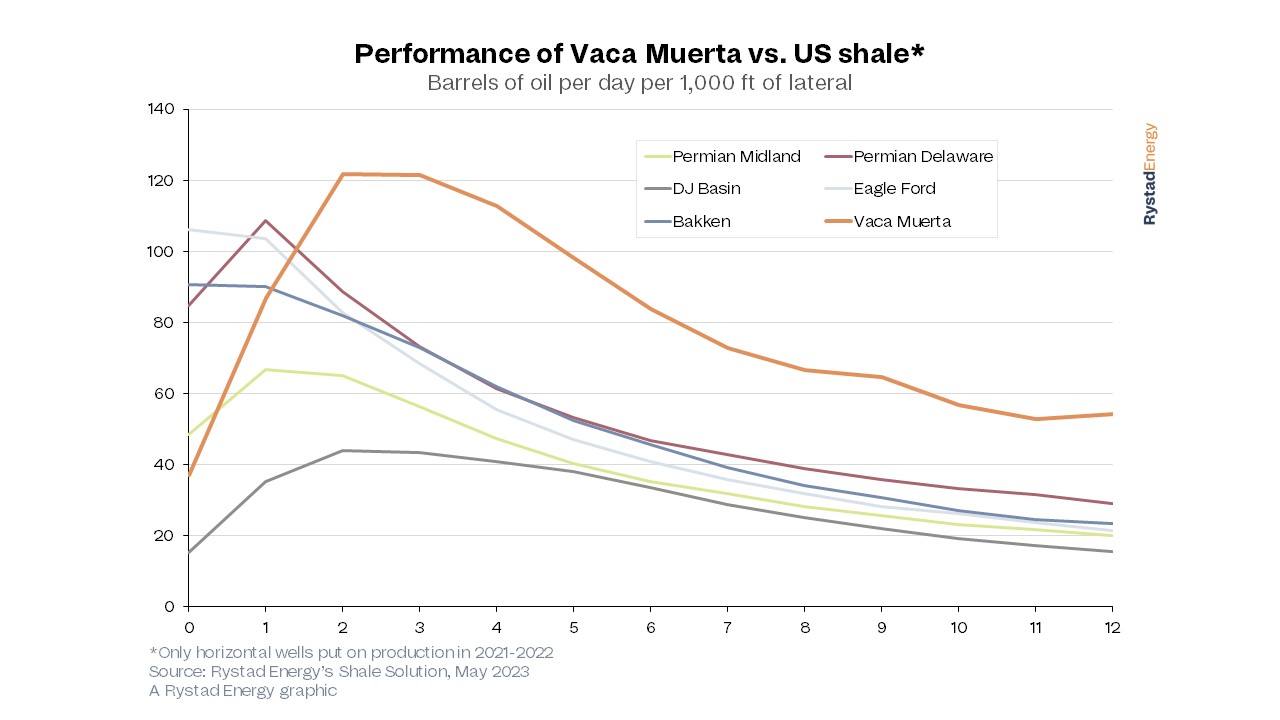

The forecasted rise in Vaca Muerta production is only possible if takeaway capacity and rig availability don’t limit growth, Rystad Energy’s head of shale research Alexandre Ramos Peon said in a report in May 2023. If production rises, it could lift Vaca Muerta’s profile and position the formation as a leading source of shale production, comparable to the Bakken or Eagle Ford developments.

Reaching a threshold of 1 MMbbl/d would pull Argentina out of its more than a decade-long production slump, reducing its reliance on imports to become a key regional and global oil market player, he said.

“In this scenario, we assume new wells that start production from now onwards have the same performance per foot as the average completed and put-on-production (POP) in 2021-2022; oil production from gas wells is negligible; capital re-investment is assured until 2030; linear growth in POP activity in 2023 and onwards,” Peon said. “For the operators, we assumed that they adopt two-mile laterals gradually within the next three years. Finally, we considered no downturns in the oil industry, global pandemics, significant macroeconomic changes or political unrest in Argentina until 2030.”

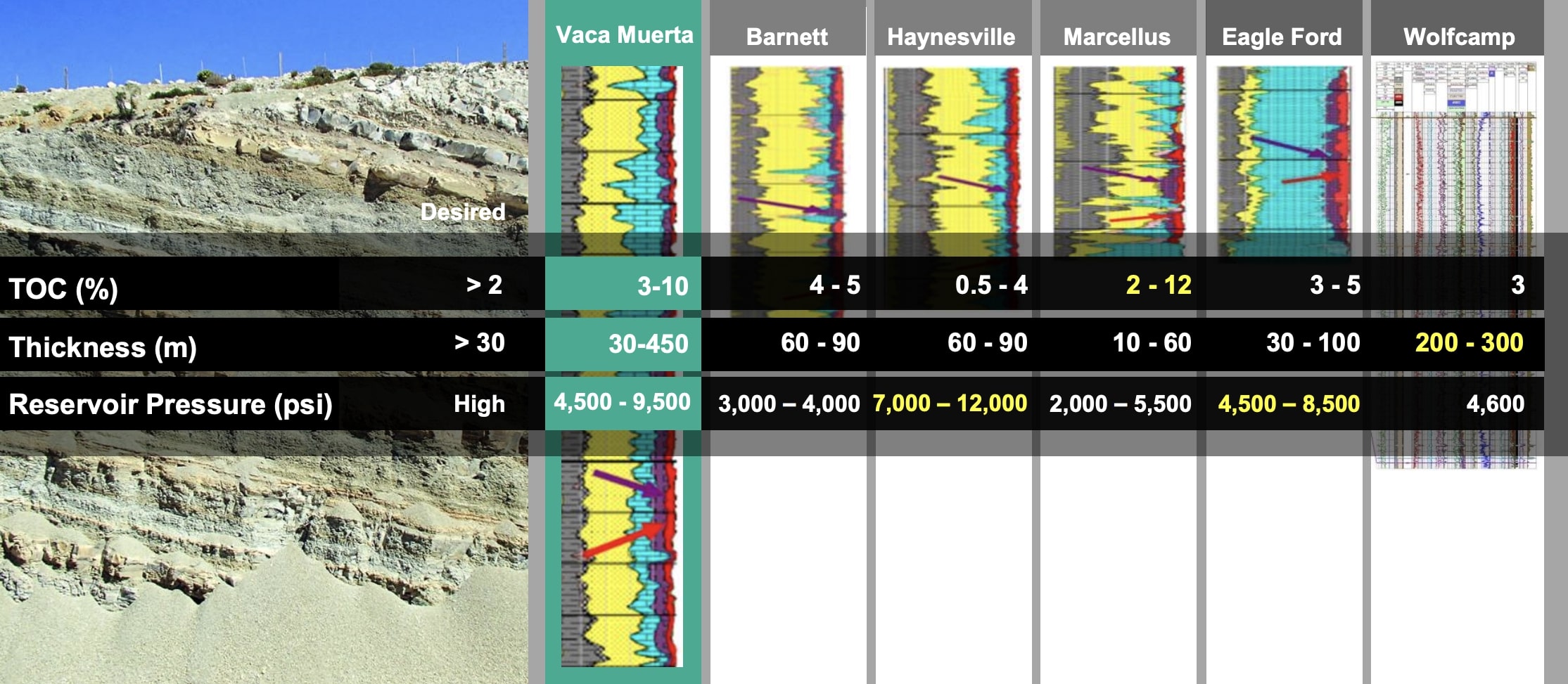

“Like some of its U.S. shale peers, Vaca Muerta’s formation is thick with stacked intervals, creating decades of high-quality drilling inventory,” Enverus said in a report on the Vaca Muerta posted to its website. “While most of the production to date has been focused on oil weighted wells, the play spans different hydrocarbon windows, creating opportunity for both oil and gas production depending on commodity pricing.”

Since the play shares many geological similarities to U.S. shale plays, Vaca Muerta operators can leverage insights from those plays to expedite the development curve, according to Enverus.

Changing Southern Cone Dynamics

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimates Argentina had around 13.6 Tcf of proved gas reserves at the end of 2020, enough to last 10.1 years. In terms of proved oil reserves, Argentina had around 2.5 Bbbls, enough to last 11.3 years.

The relatively short-lived oil and gas reserves are already a lingering energy security threat, and Argentina continues to rely heavily on imported LNG during its winter months to fulfill domestic demand. Argentine officials are hyper-focused on developing the Vaca Muerta, especially after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 as both Europe and Asia look for more secure sources of LNG to offset energy declines from Russia.

The dynamics of trading gas in South America, especially amongst the Southern Cone countries—Argentina, Bolivia and Brazil—is undergoing a dramatic change. Bolivia’s production is declining while production is ramping up in Argentina’s Vaca Muerta formation, offshore Brazil in the presalt formation and in the Equatorial margin, Rystad Energy analysts Gabriela Sanches and Vinicius Romano wrote in late November in gas report focused on South America.

“Brazil, Argentina and Bolivia are currently interconnected by a network of gas pipelines which help manage supply and demand balances between the three countries. Argentina and Brazil’s promising new gas resources could see a rejigging of this relationship in the coming years,” Sanches and Romano said. “However, the success of these plans depends on construction of critical gas transportation infrastructure in the years ahead, which could either see the region flooded with gas or choked by bottlenecks.”

In Argentina, three different routes ship gas from the Neuquén to the Buenos Aires region where key demand centers are situated. In addition to gas pipelines already in place and under the watch of Argentina’s two main gas transportation companies: Transportadora Gas del Norte (TGN) and Transportadora Gas del Sur (TGS), the country recently inaugurated the first stage of the Nestor Kirchner pipeline.

“By 2025, gas imports from Bolivia are expected to cease as part of the Argentine government’s plan to increase domestic gas production and become self-sufficient in gas supply, while also exploring export opportunities,” Sanches and Romano said.

In terms of gas exports, Argentina’s state-owned YPF SA and its Malaysian counterpart Petronas continue to eye an LNG plant on Argentina’s Atlantic Coast that would source Vaca Muerta gas and have a combined capacity of 25 million tonnes per annum (mtpa).

Monterio said he couldn’t envision a greenfield LNG project before 2030 but said an intermediate stage floating LNG project had potential to see cargoes as early as 2026 or 2027.

Upside in technically recoverable shale resources

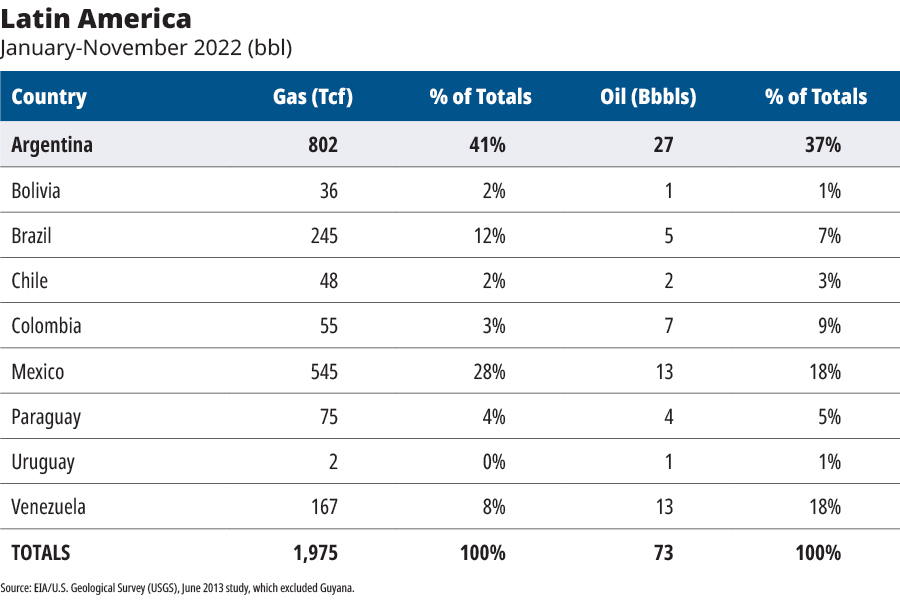

When it comes to technically recoverable shale gas resources, Argentina ranks number two in the world, according to the most recent study published by the EIA, albeit some ten years ago. In terms of shale oil resources, Argentina ranks fourth worldwide, according to the EIA.

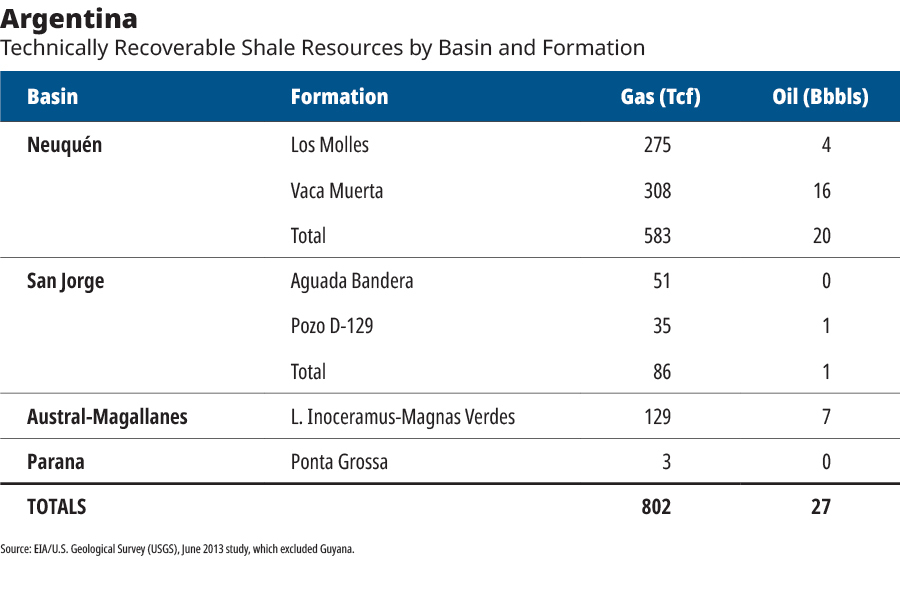

Argentina has technically recoverable shale gas resources of 802 Tcf, positioning the country only behind China, which has an estimated 1,115 Tcf.

The Vaca Muerta, situated in Argentina’s Neuquén Basin, boasts technically recoverable shale gas resources of 308 Tcf: 194 Tcf of which is dry gas, 91 Tcf is wet gas and 23 Tcf is associated gas, according to the EIA. These volumes put the Vaca Muerta on par with the Permian Basin, according to shale basin data published by Rystad.

In terms of Argentina’s technically recoverable shale oil resources, the country has 27 Bbbls. Approximately 60% or 16.2 Bbbls are located in the Vaca Muerta: 2.6 Bbbls of condensate and 13.6 Bbbls of volatile/black oil, according to the EIA. But Argentina is primarily concentrating its Vaca Muerta efforts on supply piped-gas exports and eventually LNG exports, even as oil exports continue on the uptick.

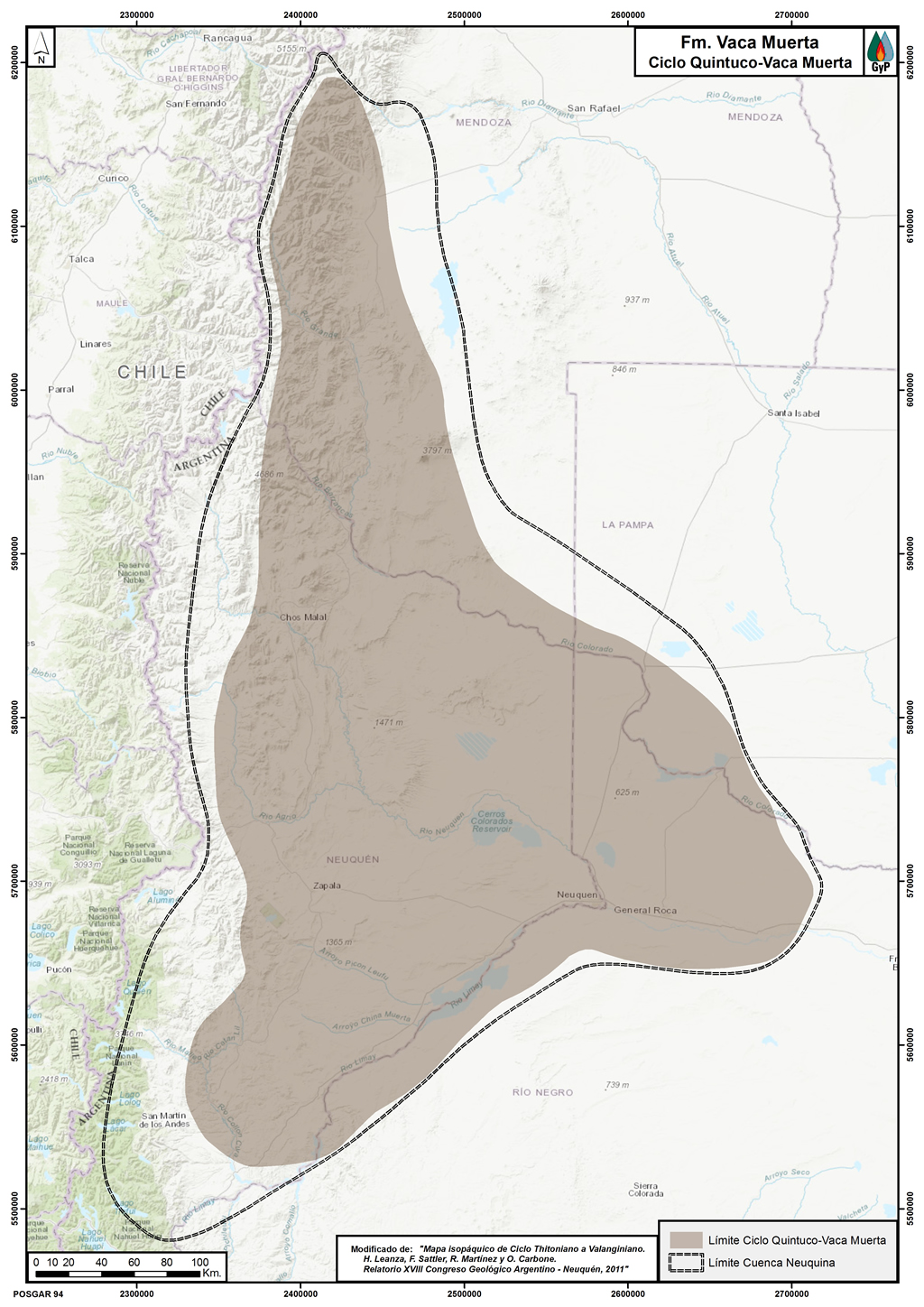

In Argentina, the Vaca Muerta formation—which crosses four Argentine provinces: Neuquén, Río Negro, La Pampa and Mendoza—is the main drilling formation targeted by companies. The formation holds 53% of the basin’s gas resources and 38% of Argentina’s gas resources.

The other major formation in Neuquén is the Los Molles, which is on the radar of companies and investors alike, but not a primary drilling focus. Neuquen has good production potential in the marine deposited Los Molles and especially the Vaca Muerta shales of Jurassic age.

In reality, Argentina has four main sedimentary basins. The other three include:

-- Golfo San Jorge, which contains mostly non-marine lacustrine shale source rocks of Jurassic to Cretaceous age;

-- Austral Basin, also known as the Magallanes Basin in Chile, which contains marine-deposited black shale in the Lower Cretaceous, considered a major source rock in the basin; and

-- Paraná, although more extensive in Brazil and Paraguay, a small area with Devonian black shale potential located in Argentina.

Vaca Muerta: geology 101

The Vaca Muerta formation in the Neuquén Basin was found when American Charles Edwin Weaver (1880-1958), doctor in geology and paleontology, noticed the cropping throughout the Vaca Muerta mountain range. The Vaca Muerta is comprised of sedimentites, called bituminous marls due to their high content of organic matter, according to the government of the Neuquén Province.

Under current plans, the Vaca Muerta is now an important part of Argentina’s economic development.

The Neuquén Basin is located in west-central Argentina and contains Late Triassic to Early Cenozoic strata deposited in a back-arc tectonic setting, according to the EIA. The basin is bordered on the west by the Andes Mountain range, on the east by the Colorado Basin and on the southeast by the North Patagonian Massif. The sedimentary sequence exceeds 22,000 ft in thickness, comprising carbonate, evaporite, and marine siliclastic rocks. Compared with the thrusted western part of the basin, the central Neuquén is deep and structurally less deformed.

The two primary shale formations in the Neuquén Basin are the Vaca Muerta and Los Molles.

The Vaca Muerta: The Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous (Tithonian-Berriasian) shale is considered the primary source rocks for conventional oil production in the basin. The formation is comprised of finely-stratified black and dark grey shale, as well as lithographic lime-mudstone totaling 200 ft-1,700 ft thick. Organic-rich marine shale was deposited in a reduced oxygen environment and contains Type II kerogen. While the Vaca Muerta is somewhat thinner than the Los Molles, its shale is of a higher total organic carbon and is more widespread across the basin.

Los Molles: The Middle Jurassic (Toarcian-Aalenian) shale is considered an important source rock for conventional oil and gas deposits. On average, the prospective shale in the formation is found at depths between 8,000 ft-14,500 ft, with maximum depth surpassing 16,000 ft in the center of the basin.

Recommended Reading

Apollo to Buy, Take Private U.S. Silica in $1.85B Deal

2024-04-26 - Apollo will purchase U.S. Silica Holdings at a time when service companies are responding to rampant E&P consolidation by conducting their own M&A.

Talos Energy Sells CCS Business to TotalEnergies

2024-03-18 - TotalEnergies’ acquisition targets Talos Energy’s Bayou Bend project, and the French company plans to sell off the remainder of Talos’ carbon capture and sequestration portfolio in Texas and Louisiana.

EQT, Equitrans to Merge in $5.45B Deal, Continuing Industry Consolidation

2024-03-11 - The deal reunites Equitrans Midstream Corp. with EQT in an all-stock deal that pays a roughly 12% premium for the infrastructure company.

Continental Resources Makes $1B in M&A Moves—But Where?

2024-02-26 - Continental Resources added acreage in Oklahoma’s Anadarko Basin, but precisely where else it bought and sold is a little more complicated.

Diversified Energy Buys NatGas Assets in Runup to LNG Exports

2024-03-19 - Diversified Energy will pay $386 million to buy 100% interest in Oaktree Capital Management’s assets in Oklahoma, East Texas and Louisiana.