During my freshman orientation at the University of New Brunswick in 1969, a very wise old professor gave some guidance on the real meaning of education. We thought schooling was about opening up our little heads and pouring in a dose of information and maybe some real knowledge. The professor pointed out that the word education has origins in the Latin ducere, meaning “to lead,” and ductilis, from which we take the word ductile. Adding the prefix, e, we understand that the true meaning of the word is the process of drawing out a person’s natural talents, strengths, and capabilities.

This tutelage was not given as license to neglect our studies but rather to establish that our time at university should be one of self-exploration so we might emerge better prepared to become all we could be. In this way, the professor lifted up the role of a mere educator to one of inspired leadership. Some 40 odd years later, I find myself precariously perched on the crest of the impending “silver tsunami” that is engulfing the oil and gas industry. Like it or not, and sooner rather than later, my generation will relinquish control, and young people, now in the trough of the wave, will lead the industry. This is an exciting prospect. My experience is that the “kids” coming into the business today are bright, curious, balanced, and aggressive about needing to know not just how to do something but why.

It strikes me that one of the most important things that we who are riding this wave can do is to become the educators of the next crew in the sense of drawing out their talents, strengths, and capabilities. But how? Let me suggest focusing on time, responsibility, and respect. First, give them your time. Through my involvement in the Society of Exploration Geophysicists I have been privileged to spend an incredible amount of time with students. I have spoken at universities, participated in student expos, and hosted countless Challenge Bowl contests. I find the students hungry to learn the technology but also curious about the business and how to shape their careers. We have a tremendous opportunity to help them along the path to success by first listening to their questions and then answering thoughtfully. This takes time, but I have come away from such encounters energized and enthused. I think I have always gotten more than I gave.

Second, I suggest you give them real work to do. I don’t mean give them jobs; rather, I mean give them responsibility as fast as they can handle it, maybe even a little faster than that. Give them the opportunity to make mistakes, and when they do, give them guidance and advice, not criticism and complaint. It does no one any good for my generation to hold on to the reins of authority until they are pulled from our failing grasp. In my experience, when you ask someone to step up and you give them the resources and encouragement to be successful, they almost always are. Finally, give them your respect. At an early stage in my career I was subjected to a real tongue-lashing by my boss, more driven by his bad mood than my performance. I practically crawled back to my office afterward, but then I turned right around and confronted the man, demanding an apology and respect in the future. To his credit he realized his error and apologized. On this new level of understanding, we went on over the years to produce some really exciting work products and became lifelong friends to boot. Both of our lives were enriched. In summary, those of us who have been around the block have a responsibility and an obligation to truly educate the next crew. Done right, it may just be the most rewarding thing we ever do.

Recommended Reading

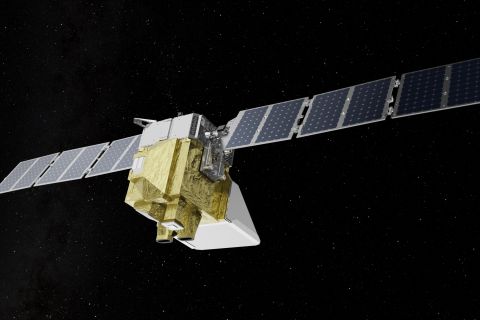

Markman: Is MethaneSAT Watching You? Yes.

2024-04-05 - EDF’s MethaneSAT is the first satellite devoted exclusively to methane and it is targeting the oil and gas space.

CEO: Linde Not Affected by Latest US Green Subsidies Package Updates

2024-02-07 - Linde CEO Sanjiv Lamba on Feb. 6 said recent updates to U.S. Inflation Reduction Act subsidies for clean energy projects will not affect the company's current projects in the United States.

Global Energy Watch: Corpus Christi Earns Designation as America's Top Energy Port

2024-02-06 - The Port of Corpus Christi began operations in 1926. Strategically located near major Texas oil and gas production, the port is now the U.S.’ largest energy export gateway, with the Permian Basin in particular a key beneficiary.

The Problem with the Pause: US LNG Trade Gets Political

2024-02-13 - Industry leaders worry that the DOE’s suspension of approvals for LNG projects will persuade global customers to seek other suppliers, wreaking havoc on energy security.

BWX Technologies Awarded $45B Contract to Manage Radioactive Cleanup

2024-03-05 - The U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Environmental Management awarded nuclear technologies company BWX Technologies Inc. a contract worth up to $45 billion for environmental management at the Hanford Site.