With a growing global emphasis on clean energy many energy companies are embracing a broader range of energy sources as they step forward with longrange projections about what the world will look like in the future. In most of these forecasts the world of tomorrow will look very different from the present, and renewables will play an expanded role.

With a growing global emphasis on clean energy many energy companies are embracing a broader range of energy sources as they step forward with longrange projections about what the world will look like in the future. In most of these forecasts the world of tomorrow will look very different from the present, and renewables will play an expanded role.

While most of the current forecasts have made 2030 their target, Eirik Wærness, senior vice president and chief economist at Statoil, has stepped farther out, looking two decades beyond the others with a forecast for 2050. He shared his outlook and insights from the seventh edition of his “Energy Perspectives” report at an event hosted by the Baker Institute Center for Energy Studies at Rice University in June.

Wærness prefaced his comments with a disclaimer that his views are not necessarily those of Statoil and that the company’s leadership, while commissioning the report, did not in any way guide it or frame it.

Three scenarios

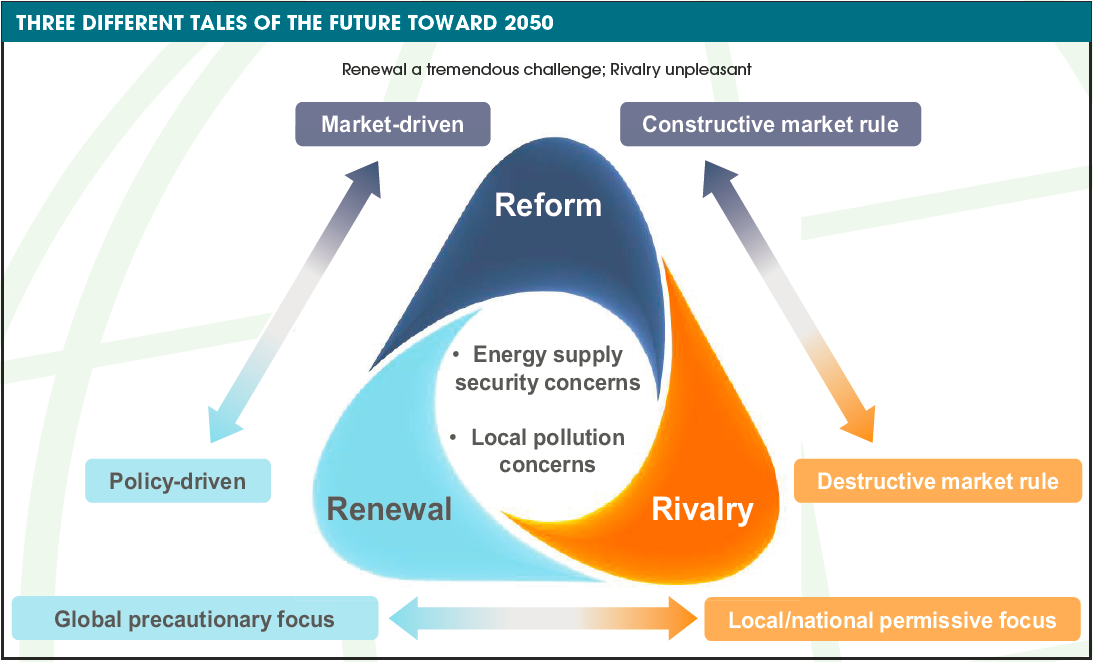

The path the world follows toward its energy future will be impacted by many factors, including how the countries of the world cooperate in framing the energy mix. Populism is changing the direction of politics in a number of countries, and a change in outlook has moved the U.S. into a lukewarm supporter of such global initiatives as the Paris Agreement. The variables that impact the future of energy are many, which expands the range of possibilities. Taking this into account, Wærness created three possible scenarios in creating his 2050 forecast.

The first scenario is reform, which he characterized as “more market-driven” and impacted by technology development. This scenario is defined as one that proceeds from current macroeconomic and energy market trends and, in climate policy terms, from the Nationally Determined Contributions in the Paris Agreement, with a gradually less prevalent role for market-correcting policies as market-based solutions drive and deliver energy-efficient and low-carbon technologies.

The second scenario, “the one we should all hope for because it delivers the highest economic growth and the lowest fuel emission,” is renewal. This scenario is driven by climate policies and agreements that join countries in a common goal. While this is not Utopia, “it is realistic in the sense that it is very likely,” according to Wærness. It presents the most positive picture. Although it is technically possible, it is a very challenging pathway to energyrelated CO2 emissions consistent with the 2 C target for global warming. The renewal scenario includes rapid and coordinated policy changes, accelerated energy-efficiency improvements and large changes in the global energy mix driven by revolutionary development in electricity generation and parts of the transport sector.

The third scenario is rivalry, what he called a “confl ict scenario” that is driven by conventional policy. “It is a scenario in which we don’t trust each other,” he explained. “We put sanctions in place against countries we don’t like. We don’t share technology. We don’t believe in free trade.” This creates an “us against them” antagonism that makes cooperation difficult in a multipolar world, where there is mounting distrust in conventional politics and policy-making and expanding protectionism and geopolitical conflict. In this scenario, the focus is on security of supply. These and other priorities overshadow global climate targets.

According to the 2017 report, all the scenarios recognize that the global population is growing, and more people are becoming part of the global middle class, which is creating economic growth that is feeding the underlying growing global demand for products, services and activities that require energy.

The spectrum covered by these scenarios is necessarily broad, Wærness said, ranging from a “global precautionary focus” on the one hand to a “national, regional, tribal rivalry” on the other.

The goal in presenting a set of scenarios is to take a broad view of possibilities and to create a forecast that looks at a range of probable outcomes. “We realize looking 33 years into the future, the uncertainties are huge,” he said.

With that admission acknowledged, there is one basic objective, Wærness said. “Instead of being precisely wrong, we hope to be vaguely right.”

The ‘Energy Perspectives’ report presents three scenarios based on different assumptions about regional and global economic growth, technological developments, market behavior, confl ict levels, and energy and climate policies. The objective is to view them collectively for a realistic impression of the very wide outcome space for developments in global energy. (Source: Statoil)

The path forward

Regardless of which scenario plays out, he said, “We need a fantastic, absolutely mind-boggling improvement in global energy efficiency” if the world is to get a handle on its energy usage. In fact, for any substantive measure of success, “We will need to improve energy efficiency much more rapidly than we have to date,” he said.

Even for the renewal scenario, which Wærness describes as the most realistic of the three, it will be extremely difficult to achieve the targets he has put forward. This scenario projects a fall in energy demand of 6% from 2014 to 2050, during which time the economy is expected to be 2 to 2.6 times larger and the population will have grown by 2.4 billion people.

In the reform scenario demand is expected to be 25% higher, and in the rivalry scenario it is 30% higher.

To achieve the goals of the renewal scenario, energy efficiency will have to be improved globally “three times faster in the next 35 years than in the last 25,” he said.

So how will efficiencies be achieved? Wærness provided one simple example: The world might have three times as many aircraft on earth in 2050, he said, but they may be powered by something other than jet fuel and very possibly will operate from a fuel source that emits considerably less CO2.

While technologies could be transformational, they alone will not get the world to this objective. Behavioral changes will be critical. “We should not underestimate the needed transformation in terms of energy efficiency improvements, fuel mix changes and modified consumer behavior,” he said.

There is a significant need for new oil and gas investment in all scenarios because production from existing reserves cannot keep up with demand. Coal demand is the most important key to global CO2 emission levels in all the scenarios, Wærness explained, noting average annual growth rates vary from -3.1% to 0.4%, resulting in coal demand in 2050 that could range from 30% to 110% of the demand level in 2014. That is an enormous range of possibilities.

There also is a need for investment in new renewable sources of electricity. In particular, solar and wind energy use will have to increase significantly, delivering between eight and 18 times more electricity in 2050 than in 2014.

Achieving that level of renewable energy output will be extremely challenging. “We have 200 times more solar panels now than we did in 2000,” Wærness said, which on the surface looks impressive. But while this seems like great progress, it amounts to less than 2% of the energy mix. “Decarbonization has to speed up if we’re going to get CO2 emissions down,” he said.

Clearly, “this will not be a walk in the park,” he said, but there is hope on the horizon, and collaborative and cooperative efforts will be the instruments of change.

“The renewal scenario is a bold hope,” he said. “It requires us to stop talking targets and start implementing measures to achieve them.”

In the end, the effort will pay enormous dividends. “After all, we are the ones who benefit from global climate change not happening,” he said.

Recommended Reading

BP’s Kate Thomson Promoted to CFO, Joins Board

2024-02-05 - Before becoming BP’s interim CFO in September 2023, Kate Thomson served as senior vice president of finance for production and operations.

Magnolia Oil & Gas Hikes Quarterly Cash Dividend by 13%

2024-02-05 - Magnolia’s dividend will rise 13% to $0.13 per share, the company said.

TPG Adds Lebovitz as Head of Infrastructure for Climate Investing Platform

2024-02-07 - TPG Rise Climate was launched in 2021 to make investments across asset classes in climate solutions globally.

Air Products Sees $15B Hydrogen, Energy Transition Project Backlog

2024-02-07 - Pennsylvania-headquartered Air Products has eight hydrogen projects underway and is targeting an IRR of more than 10%.

HighPeak Energy Authorizes First Share Buyback Since Founding

2024-02-06 - Along with a $75 million share repurchase program, Midland Basin operator HighPeak Energy’s board also increased its quarterly dividend.