By Marc Champion, Bloomberg Amazingly, tens of thousands of Ukrainians are still braving the winter cold to protest what they consider to be the sale of their country's future to Russia. A big part of the deal in dispute was what Russian President Vladimir Putin described as a "fraternal" 33% discount on the price that Ukraine pays for natural gas imports. So why aren't Ukrainians more grateful to their bigger brother? Maybe they have done the math – which shows it really isn't such a bargain after all. There are two major elements to the agreement: a US $15 billion loan pledge and a reduction in the price of natural gas imports from about $400 per 1,000 cm to $268.50. The average price that Gazprom charges to European Union countries for long-term contracts is $370 to $380. So it sounds as though Ukraine will now get a big discount – plus a generous bailout. Not quite. The gas has to cross Ukraine to get to EU markets, and the $370-$380 that Gazprom charges countries such as Germany includes the cost of that transit. Ukraine charges about $3 per 1,000 cm per 100 km. The distance from the Ukrainian border with Russia to the big European hub at Baumgarten, Austria, is about 1,800 km (1,118 miles). So subtract about $50 from the European gas price to get closer to a true equivalent. Then consider that the EU now has a hub, or spot market price for gas that's often lower than Gazprom's. "What I find interesting is that $268.50 isn't so far off the European hub price, once you deduct transit costs," says Simon Pirani, a senior research fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, who specializes on the gas trade in the ex-Soviet Union. When Ukraine struck its gas contract price with Russia in 2009, it was under threat of another cutoff of its gas supply, as had occurred in 2009, 2008, and 2006. The thinking behind the new price was that Ukraine should start paying the European price for gas, in exchange for independence. Think of Ukraine as a natural gas junkie, addicted to cheap Russian fuel. Before 2006, this relatively poor country – which has a population of 46 million and an economy 19 times smaller than Germany's – had been consuming almost 80 Bcm (2.8 Tcf) of gas annually. Germany was consuming just under 100 Bcm (3.5 Tcf). Ukraine had been paying just $50 per 100 cm for Russian gas imports. So something had to change. The formula reached in 2009 was index-linked to the price of oil. Three things then happened: The price of oil rose; the EU started to link up its natural gas grids to create a spot market at the gas hubs, independent of Gazprom's long-term contracts; and demand for gas within the EU fell. Indeed, without a renegotiation in 2010 (Russia got extended naval basing rights in exchange), Ukraine would now be paying $500 per 100 cm of gas. The reduced price Ukraine pays to Gazprom is still so out of kilter that it is about $30 cheaper to buy gas the EU has imported and transport it back across the border. This re-importing had started to happen on a very small scale from Poland and Hungary. And on Dec. 9, Slovakia's gas transit company Eustream agreed on terms to reverse the flow in one of its big transit pipes. With the necessary Slovak capacity, Ukraine might have been able to fulfill the deal it has to buy 10 Bcm (353 Bcf) of gas annually from Germany's RWE AG. That would represent about a third of Ukraine's current imports from Russia, which had already fallen substantially because of Ukraine's declining gas consumption, due to a collapsing economy, coal substitution and efficiency improvements, according to Pirani. Faced by competition from EU re-suppliers, Gazprom would in any case have had to choose: risk losing as much as another one third of its gas sales to Ukraine and associated political leverage, or else reduce its price by a third to make EU re-imports uncompetitive. In sum, it's clear that the $268.50 discount offered to Yanukovych wasn't as generous as it sounds. Putin in essence agreed to stop extorting money from Ukraine and charge the market price. So how about the $15 billion loan? Russia bought the first $3 billion of Ukrainian eurobonds as promised just before Christmas, at a coupon rate of 5%. Ukraine had an alternative source for a $15 billion bailout loan, from the International Monetary Fund. The interest rate payable to the IMF probably would have been cheaper by 2 percentage points or more. The difference between the two loans is, again, best looked at in terms of an addict and supplier. The IMF was offering rehab, a painful treatment that would have involved: devaluing the currency; reducing energy subsidies worth about 7.5% of gross domestic product; making other budget cuts in areas such as pensions, which account for as much as 18% of GDP; and structural reforms. Russia's loan was free of known strings, except those that bind a hopeless debtor to his creditor. What the Russian money does better is fund Yanukovych's 2015 election campaign. Prime Minister Mykola Azarov immediately started announcing how the money will be spent, including increases to the minimum wage, child benefits and public sector pay raises – everything the IMF would oppose. The IMF loan terms would have been better for Ukraine. The Putin deal is better for Yanukovych. No wonder some Ukrainians plan to take to the streets again to call for his resignation on New Year's Day, even if their cause appears to be lost. Marc Champion is a Bloomberg View editorial board member.

Recommended Reading

‘Oversupplied’ NatGas Market Aiding Williams’ Storage Business

2024-05-08 - Midstream company Williams saw overall demand growth as heavy gas volumes passed through its network.

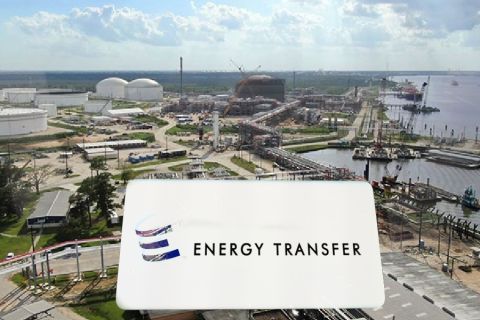

Energy Transfer Eyes Draft Environmental Statement for Blue Marlin Project This Quarter

2024-05-09 - Energy Transfer is among several firms vying to build deepwater ports along the Texas Gulf Coast.

Energy Transfer Remains Hungry for M&A, Sees 1Q Oil Volumes Surge

2024-05-09 - Energy Transfer reported record first-quarter crude volumes and expects demand for petrochemicals to continue rising.

Enbridge Plans to Increase Permian Oil Pipeline’s Capacity

2024-05-10 - Midstream company Enbridge announced an open season on the Gray Oak Pipeline for a proposed 120,000 bbl/d expansion and updated its M&A efforts.

Developer Seeks Permit to Send US Gas to Mexico for LNG Exports

2024-05-22 - The project is the latest in a series of developments to convert U.S. gas into LNG and export it from Mexico's Atlantic and Pacific coasts to meet global demand.