Natural gas flares from a ship near a Fieldwood Energy operated drilling rig and an FPSO at its Ichalkil well offshore Mexico.

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the July 2018 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

On the surface, Matt McCarroll was calm—even optimistic. The founder and CEO of Fieldwood Energy LLC authored an audacious plan to rescue his company.

Fieldwood would buy Gulf of Mexico (GoM) deepwater assets from Noble Energy Inc. (NYSE: NBL) for $480 million in cash. Simultaneously, it would enter Chapter 11 bankruptcy, hauling more than $3 billion of debt into a courthouse to reorganize its finances.

The company would also have to turn back a wave of skepticism.

“Simultaneously, this was not a typical bankruptcy, and I think anyone who is in the business of restructuring or [who] deals with that will share that view,” McCarroll told Hart Energy's Oil and Gas Investor. “We had a business that was profitable. We didn’t need to fix the business. We needed to fix the balance sheet.”

Fieldwood was at the end of a financial rope frayed by crippling oil prices that had made its debt-service payments unmanageable. “The only thing that was going to help us de-lever the balance sheet was significant incremental cash flow,” McCarroll said.

The company needed a huge drilling success or an acquisition with immediate cash flow. But the company couldn’t afford a deal and had no money to drill.

McCarroll thought he had hit upon a way to repair the balance sheet: Buy Noble’s GoM producing assets—which he’d been after for months—and inherit the cash flow.

It was the antithesis of many bankruptcies—in which E&Ps often sell off assets to raise capital.

Fieldwood’s timing had to be perfect. Once in court, the plan had to hold in place. Operations had to remain up and running. A federal bankruptcy judge would have to give the prepackaged restructuring plan his blessing.

The deal had to close.

Natural gas flares from a ship near a Fieldwood Energy operated drilling rig and an FPSO at its Ichalkil well offshore Mexico.

For this, McCarroll’s job was to seal off the bankruptcy from all but a handful of staff. As in The Art of War, “the good general [was] full of caution.”

McCarroll was adequately wary. He’d never been through a restructuring process and found it discomfiting. Many nights, McCarroll would return home and think, “I don’t know if this is ever going to work out.”

But McCarroll always projected confidence. At Fieldwood’s offices in Houston, he reassured staff that the restructuring was going fine. “Guys, don’t worry,” he recalled telling them. “Keep working hard. This is all going to work out great for all of us.”

He preempted his children’s worries. “You’re going to read in the paper tomorrow morning that Dad’s company filed for bankruptcy,” he told them. “I’m not losing my job. It’s OK.”’

Still, he could imagine all the ways the plan to rescue Fieldwood from prolonged bankruptcy could fall apart. It was a gut check.

His bold deal began with calling Noble. He began his pitch: “We’ve got this crazy idea.”

The response: “How in the [world] would that work?”

Numerous restructuring advisers took some convincing too.

Breaking Wave

On a wall in Fieldwood’s conference room is a framed spoof of Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours album retitled as “Fleetwood Matt: The GOM Dance 2.0.”

In 2013, CEO of Apache Corp. (NYSE: APA), at the time, Steve Farris addressed employees in the same office building, saying Fieldwood would buy the company’s GoM assets for $3.75 billion. Fieldwood had just five employees at the time but raised a company banner in the office. “Steve introduces me to the employees,” McCarroll said: “You’re going to love working with Fleetwood and Matt.”

It stuck. At the close of the deal, everyone involved put their names on the mock album cover as a closing gift.

Fieldwood closed the Apache deal in September of 2013. The following February, Fieldwood added GOM assets from SandRidge Energy Inc. (NYSE: SD) for $750 million, bringing its A&D bill to $4.5 billion.

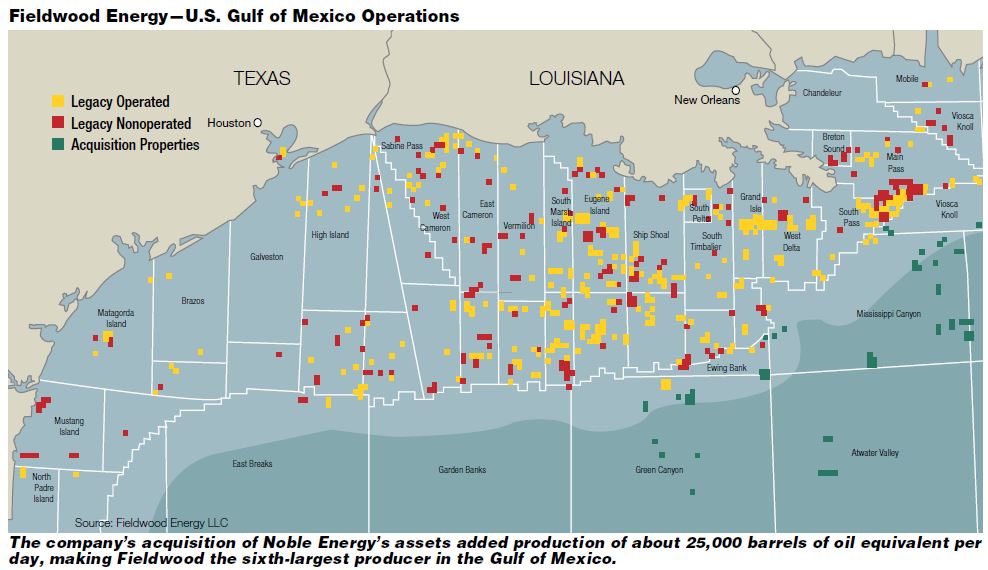

Fieldwood’s empire stretched from Mustang Island, just off Corpus Christi, Texas, to Alabama’s Mobile Bay. But the price of those deals lingered on its balance sheet. Nearly all of Fieldwood’s $3.2 billion of debt was derived from these two acquisitions; annual debt service was more than $250 million. By 2017, the toll of weak commodity prices began to drain the company. By summer, Fieldwood brought in advisor Evercore Group LLC to consider restructuring options.

Even early on, McCarroll was interested in an acquisition, said Evercore’s David Ying and Pranav Gupta. “Even we, initially, said that would be very difficult because, at the time, we weren’t sure Noble was out there [to do a deal] and we didn’t have a specific counterparty to work with,” Ying said.

In the past 30 years, Ying has shepherded two companies through bankruptcies that included acquisitions. “It is very, very unusual,” he said.

The other stumbling block was wrapping investors’ minds around the logic of a deal at a time of financial distress. “Obviously, people have had a hard time of grasping this concept of combining an acquisition with a capital restructuring without a specific target in mind,” Ying said.

Evercore advised McCarroll to keep life simple, at least for the moment, “and just go down the path of doing a plain, regular, balance sheet restructuring.” However, negotiations with creditors made it clear a “plain, vanilla, balance sheet restructuring” would prove difficult.

“I have to tell you it wasn’t easy. People were not happy. We had to convert a lot of debt to equity, which caused a lot of consternation among the creditors,” he said. The concept of integrating an acquisition into the restructuring plan started to make sense.

In a matter of days, McCarroll took an evaluation of the Noble assets to investors. Initially, he wanted to raise new capital to drill. Now, instead of strictly drilling wells, “we’re going to buy these Noble assets and they will generate the cash flow” to fund a drilling program.

The Noble assets produce about 25,000 barrels of oil equivalent a day, about 85% oil. They generate about $25- to $30 million a month in net cash flow.

At January WTI, they would generate about $300 million in EBITDA in 2018. By late May, WTI had risen by about $20 per barrel.

The acquisition crystallized for investors a way forward that would also provide incremental value. Ying said the deal “helped solve a lot of problems. It actually created a much more compelling use of proceeds for the equity that needed to be raised to fix the capital structure.”

By the time Evercore agreed to propose it to creditors, they had named the restructuring-plus-acquisition deal “Plan A.”

“And we had a Plan B. And, just to keep it straight, we said Plan ‘B’ is for ‘Bad,’” Ying said, laughing. Plan B was a restructuring that still remained to be worked out.

Creditors gravitated almost immediately to Plan A. Fieldwood’s acquisition-heavy business strategy made it a fit as well.

“It’s an unusual case where Matt’s been in business a long time,” Ying said. “He has a very good reputation and track record as an operator in the Gulf. The creditors who own this paper have hung in there with him through the low oil price scenario. And they believe in him and his ability to operate his assets.

“The people who were skeptical were a lot of the advisers,” he said. “It does complicate the restructuring, bringing in a third party” to sell an asset.

The magnitude of the changes being proposed to Fieldwood’s capital structure would, under bankruptcy law, require the consent of all the creditors. Entering bankruptcy would require approval of two-thirds of creditors in each class of the capital structure. “Because we knew we could get two-thirds of the creditors, we went to the bankruptcy court,” Ying said.

Fieldwood backer Riverstone Holdings LLC was also integral to the company’s survival. It and other second lien holders deferred interest payments due to help Fieldwood’s negotiations and smooth the road for a prepackaged deal.

“I can’t underestimate the support the company got from Riverstone to make this happen,” Ying said.

Fieldwood’s plan began to take shape. The company would eliminate about half of its debt—$1.6 billion—by giving senior creditors new equity interest. Fieldwood would also raise about $525 million in cash through a rights offering to second-lien creditors.

The end result would be a bigger, stronger and more valuable company. Fieldwood’s debt service would also fall to about $100 million a year from more than $250 million.

All that was left was bankruptcy—the filings, court hearings and a bankruptcy judge to sign off on the restructuring.

And then, of course, Fieldwood needed to close the deal.

Hostile Environment

The first reaction to McCarroll’s proposal, from almost everyone, was extreme skepticism. “I think that was most people’s reaction, even on our side,” said Chris Klawinski, vice president of business development at Noble Energy.

Klawinski’s job, however, isn’t to say “no.” “My job is to evaluate opportunities and make sure we think it through.”

A divestment to an operator that was planning to enter Chapter 11 as part of the deal was unlike any he’d been presented, but he had a different take than most.

“I had a certain comfort level,” he said. “I used to be a practicing attorney. So my initial reaction is, ‘it’s definitely different but I’m willing to hear it out,’” he said.

For Noble, the sale of its GoM assets wasn’t a matter of who could write the biggest check. The company had other suitors.

Since acquiring Clayton Williams Energy Inc.’s Permian Basin position in April 2017, Noble had been approached about several of its assets, including its GoM deepwater blocks.

The assets were compelling based on their production alone. The blocks also held other potential development opportunities. But the GoM’s decline rate and its growth potential couldn’t compete for capital within the top tier of the company’s portfolio.

Nevertheless, Noble wanted a buyer that could take over the assets and give them the attention they needed. That included taking over financial commitments, including abandonment obligations Noble estimated at $230 million.

“McCarroll was able to do that,” he said. “He’s been working the Gulf of Mexico his whole life.”

Klawinski’s chief concern was making sure—before it went to the board—that the sale would have a high probability of closing.

“We didn’t want to announce a deal and not have it close,” he said. “I think it has an impact on operations—on your workforce and what they’re focused on—and that’s not what we wanted to have happen.”

The deal, on its own, isn’t much different from other deals, though no two are really alike, he said. “They all have a life of their own. They all pick up their own cadence,” he said.

Due diligence was particularly critical for Noble. Klawinski’s team scrutinized projections, particularly on Fieldwood’s leverage and any other assets that they owned.

Prior to bankruptcy, Fieldwood’s leverage was about 5.9x its projected 2018 EBITDA. Reorganizing, the company projected it would drop to 1.9x.

Despite the optics of a bankrupt buyer, there was general optimism the deal would work.

“The key to any successful deal is that moment when there’s no façade. There’s no ‘I’m the negotiator.’ I’m sitting at a table, and I’m just trying to work through issues with somebody on the other side constructively in a way that makes it work for them and makes it work for us.”

McCarroll’s openness throughout the negotiations helped. “The quicker you get to that moment in a negotiation, the quicker you can get to a finish line,” he said.

Noble’s willingness to be patient was essential, Ying said. But Noble also got a responsible owner in Fieldwood. “It’s a hostile environment, operating in the Gulf,” he said.

“Matt was one of the few people qualified to do it. It did require their cooperation and patience because this wasn’t your typical deal.”

On Balance

Some bankruptcies plod along. Ying worked on a reorganization involving TXU Energy and other parties that dragged by for three years.

Fieldwood’s reorganization was a sprint: Just 45 days passed between filing and the court’s confirmation of the plan. Fieldwood entered Chapter 11 with nearly unanimous support. Among parties voting, 100% approved the plan. Even the judge, David R. Jones, seemed impressed. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen a recapitalization and a sale all encompassed within one plan, honestly,” he said in court. “I think it’s an incredibly efficient use of the process.”

Jones waived a standard 14-day waiting period so Fieldwood could move ahead with the acquisition. And he added a note of congratulations.

“The fact that the transaction that you got done efficiently will allow other commercial transactions to take place and capital investment to be made … you should all walk out today proud of what you’ve done. I certainly am,” he said.

Still, closing day was intense.

“The guys at Fieldwood were trying very hard to get everything buttoned up and get all the different pieces synced at closing,” Klawinski said. “It was also a sense of excitement for both sides when we finally closed.”

McCarroll has mixed feelings about the bankruptcy, largely because the original equity investors lost their investment.

“That’s really the big negative to come out of this,” he said. “That said, most of those investors still have a material interest in the company and still have a good opportunity to make a return on their original invested dollars.”

But his conditions for entering bankruptcy in the first place were met. He wanted a lasting solution to the company’s balance sheet. His insistence that the company’s operations were sound is borne out by its time in bankruptcy. Fieldwood was obligated to secure $60 million in debtor-in-possession financing. The company never needed a penny of the money.

The judge remarked from the bench, “In order for any restructuring to succeed, all eyes have to be looking forward, and I think that’s often overlooked.”

McCarroll also refused to compromise the people who relied on the company: employees, contractors and vendors.

“If we had to go into a Chapter 11 process,” he told his advisers, “we’re not going to use a bankruptcy filing to cancel or reject contracts, to leave financial obligations or abandonment obligations behind. We’re not going to impair our vendors.”

To assuage any concerns regarding its intentions, Fieldwood met with each of its more than 700 vendors. Just one—American Express—stopped doing business with the company, despite a two-month advance payment and extensive efforts by Fieldwood to maintain the relationship.

McCarroll wanted to keep his word and his reputation. Over the course of his career, he’s built trust with suppliers and contractors. Fieldwood is in the GoM for the long haul. It’s all the company does. Following bankruptcy, it awarded raises to its contractors. Fieldwood still plans to drill. It’s already working on a block offshore Mexico; it was among the first foreign operators to drill in Mexico in roughly 80 years.

With Noble’s production, Fieldwood is now the sixth-largest GoM producer. McCarroll is unfazed by such statistics.

“Our goal is to be the best producer, the safest, the most regulatory compliant, the most profitable, the best company to do business with, the best place to work,” he said.

In 1977, about 170 miles southwest of New Orleans, McCarroll spent a college summer working for Mobil Oil Co. on a new platform in Eugene Island, Block 330. He painted and read gauges.

“We now own that platform,” he said. One day, he hopes to revisit it to see if it’s the way he remembers and how it’s aged and weathered since then.

For now, though, McCarroll is looking only toward the future—into ocean waters deeper and more promising than ever.

Darren Barbee can be reached at dbarbee@hartenergy.com.

Recommended Reading

Equinor Subsidiary Contracts Valaris Drillship Offshore Brazil

2024-07-22 - Valaris and Equinor Energy do Brasil’s multi-year contract is valued at approximately $498 million.

Offshore Guyana: ‘The Place to Spend Money’

2024-07-09 - Exxon Mobil, Hess and CNOOC are prepared to pump as much as $105 billion into the vast potential of the Stabroek Block.

Liberty Energy Warns of ‘Softer’ E&P Activity to Finish 2024

2024-07-18 - Service company Liberty Energy Inc. upped its EBITDA 12% quarter over quarter but sees signs of slowing drilling activity and completions in the second half of the year.

CEO: Baker Hughes Lands $3.5B in New Contracts in ‘Age of Gas’

2024-07-26 - Baker Hughes revised down its global upstream spending outlook for the year due to “North American softness” with oil activity recovery in second half unlikely to materialize, President and CEO Lorenzo Simonelli said.

Petrobras CEO Prates to Step Down

2024-05-15 - Brazil’s President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has requested that Petrobras CEO Jean Paul Prates resign following a dispute over dividend payments.