Hillary Holmes has heard it before and will hear it again.

The reason there are so few women in C-suites and boardrooms across the oil and gas industry, a leading male industry executive explained to her recently, is that there aren’t many qualified women to move into those positions.

“My response is always, if you can’t find women to add to the leadership ranks, to your directors and to your C-suites in this industry, then you’re not looking hard enough,” Holmes, partner in the Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher law firm, told Hart Energy. “And you’re not using forward-thinking and being innovative about where to find that talent.”

The workplace diversity issue boils down to two salient points:

- A company will only achieve a diverse workforce across all levels, including the C-suite, when its CEO is committed to diversity; and

- Companies with diverse workforces make more money.

A STEM-energized education system nearly doubled the annual number of engineering degrees awarded from 1990 to 2018, according to data from the National Science Foundation and Engineering Workforce Commission, with the absolute number received by women soaring 172.5% during that time.

So, the talent is there, but the oil and gas industry struggles to attract and retain it.

The numbers are telling: women account for 57% of all college graduates and 35% of graduates in STEM fields, according to the Brookings Institution. However, they only account for 13.9% of graduates in mechanical engineering and 17.1% in petroleum engineering.

“The industry’s appeal is declining among younger people,” said McKinsey & Co. in its “How women can help fill the oil and gas industry’s talent gap” report. “A decade ago, oil and gas was the 14th most attractive employer among engineering and IT students; now it is 35th.”

Why?

Where did they go?

“Part of it is an image issue,” Holmes said. “It’s historically been a male-dominated industry and white-dominated industry. I think maybe some of the talent coming out of colleges or coming out of vocational schools that make this industry as strong as it is, they are just not putting oil and gas jobs on their list.”

But the industry does succeed in hiring thousands of new grads each year. A survey by the World Petroleum Council of young oil and gas employees showed enthusiasm for participating in the energy transition. Working in a multicultural and high-tech environment were also high priorities for both men and women under 35.

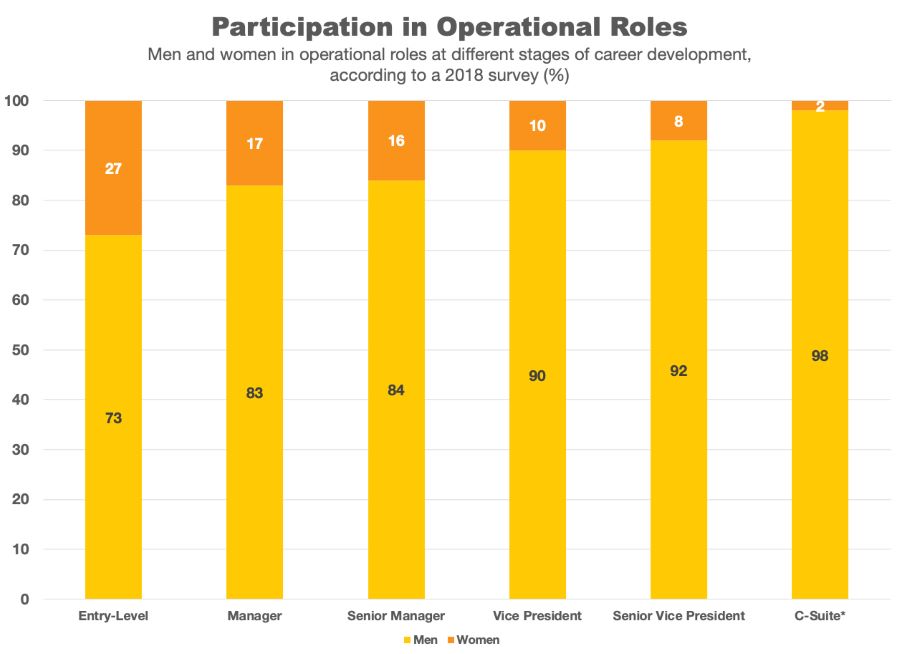

These are ambitious, long-term goals. But we know what happens next. Woman constitute more than one in four entry-level workers in the oil and gas industry, but only one in six managers, one in 10 vice presidents and one in 50 in C-suite roles. As the Conference Board found in 2021, the energy business was not just the worst among major sectors in the number of women CEOs but was trending downward.

Fending off poachers

Where did the enthusiasm for bringing about the energy transition go among one of three young women working in the energy field? Where did the workers go?

Some were laid off. When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, the oil and gas industry let go 76,000 people, or 21% of its Texas workforce, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. It has since hired back about half of that total. Those who stayed witnessed how quickly a career can be upended in a cyclical industry.

Others were simply poached by competing industries such as utilities, renewables and technology.

“There are tons of them that went to Apple, Meta or Google, and they’re not coming back,” Katie Mehnert, founder and CEO of Ally Energy, told Hart Energy. “And it’s because they’re getting the pay and they’re getting the flexibility, and this is where oil and gas and energy needs to become more competitive.

“A lot of folks are leaving. A lot of people walking out the door, saying, ‘You know, I can get more down the road in the tech industry than working in energy.’”

Holmes has seen it too.

“It’s something oil and gas companies should pay attention to, but it’s also a playbook that we can learn from,” she said. “Let’s pull talent from tech companies. Let’s pull talent from … an energy transition or energy expansion company. There are some carbon capture companies I work with now that you would consider innovative. Several of those, their leadership teams are comprised of former oil and gas executives.”

The talent drain is not necessarily a diversity issue, but it highlights the sector’s retention problems.

Money follows the diversity

“An oil and gas company is not going to be successful if it can’t attract the top talent, and it’s not going to attract the top talent without an effective and clear diversity strategy,” she said.

Empirical data support the notion that companies across all industries that are more diverse experience bigger profit margins. McKinsey & Co. found that companies in the top quartile for gender diversity on executive teams were 21% more likely to have above-average profitability than companies in the bottom quartile. Top-quartile companies in ethnic and cultural diversity were 33% more likely to outperform on profitability.

Energy)

Harvard Business Review examined an industry that, like energy, is dominated by white males. The research revealed that performance in the “staggeringly homogeneous” venture capital (VC) industry—only 8% of VC investors are women, 2% are Hispanic and less than 1% are black—was improved by diversity. An investment’s comparative success rate was reduced by 26.4% to 32.2% when executed by a team of shared ethnicity.

That success was echoed on the gender diversity side.

“Venture capital firms that increased their proportion of female partner hires by 10% saw, on average, a 1.5% spike in overall fund returns each year and had 9.7% more profitable exits (an impressive figure given that only 28.8% of all VC investments have a profitable exit),” the authors wrote.

Fortunately, the oil and gas industry has made significant strides in that direction.

“The vast majority of the oil and gas companies I work with have taken affirmative steps to improve diversity, at least at the leadership level,” Holmes said. “At least in their boardroom—those that are publicly traded—at least in their C-suite to the extent possible.”

Starts at the top

To reap the benefits, it’s critical that a company’s leadership reflects the characteristics they want from their broader workforce. If oil and gas CEOs commit to gender balance, the World Petroleum Council said in its report, the organizations will follow.

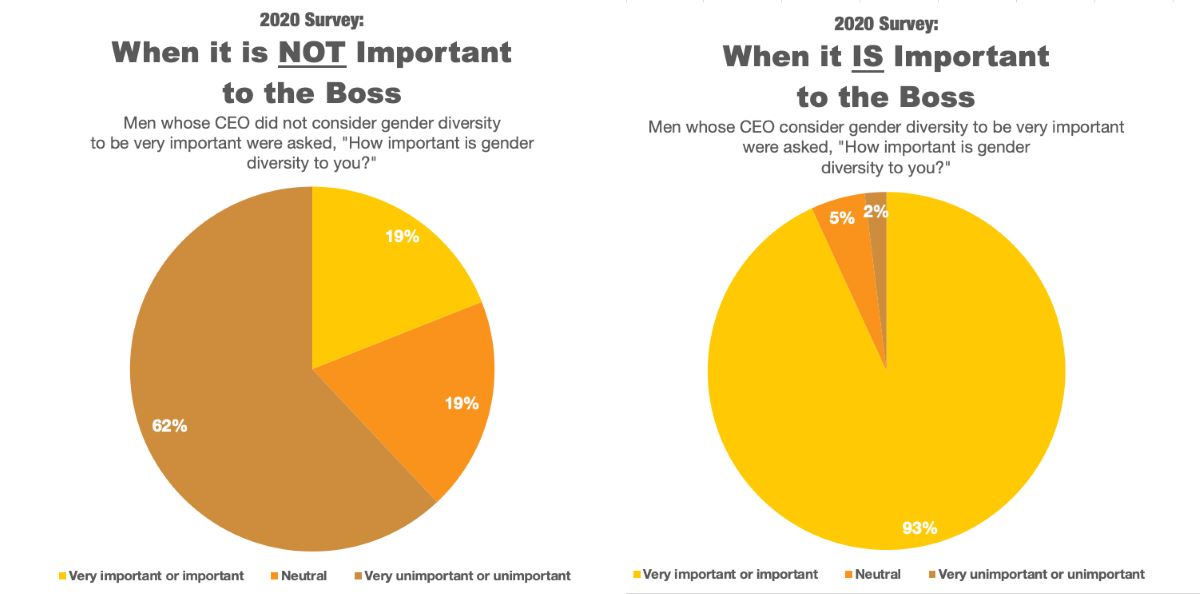

The comparison charts of surveys of male oil and gas employees conducted in 2017 and 2020 bear that out. When gender diversity was not important to the CEO, it was not important to 59% of the male employees, either, in the 2017 survey. When it was important to the CEO, that view was shared by 86% of male employees.

An interesting shift took place between 2017 and 2020 among those working for a CEO for whom gender diversity was not important. In 2017, 34% of the male workforce thought gender diversity was important, contrary to what the boss thought. After three more years of working for a CEO who did not consider it to be important, that percentage dropped sharply to 19%.

On the flip side, the share of men who’s CEO saw gender diversity as important grew to 93%, with the percentage considering it unimportant or very unimportant diminished to 2%. Either way, the boss set the tone for the workforce.

“To provide effective leadership in this area, leaders must consistently and frequently reinforce the strategic importance of D&I [diversity and inclusion], through their actions and their words,” the report’s authors wrote.

Holmes would like those who lead the oil and gas industry to think more broadly about the talent pool and make it a priority.

“A woman shouldn’t get a job just because she’s a woman,” she said. “But the board or the C-suite should always be thinking: Is our management team bringing diverse perspectives?”

That includes diversity of experience, age, gender, race and other characteristics on the matrix.

“If we do,” Holmes said, “then that will contribute to a more profitable company.”

Recommended Reading

States Sue US to Block Rule That Oil Firms Guarantee Payment to Dismantle Old Wells

2024-06-17 - The lawsuit was filed against the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management to block the proposed rule that would require the offshore oil and gas industry to cover costs of dismantling old infrastructure.

SLB: ‘As Expected’ ChampionX Deal to Undergo More Regulatory Review

2024-07-03 - Aggressive enforcement by the Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission has delayed multiple high-profile, multibillion dollar oil and gas deals, with SLB’s ChampionX deal the latest.

Noble’s $1.59B Diamond Offshore Acquisition Clears Antitrust Hurdle

2024-07-26 - Noble Corp.’s acquisition of Diamond Offshore Drilling still requires approval by Diamond shareholders as well as regulatory authorization in Australia.

FTC Requests More Info on $17.1B ConocoPhillips, Marathon Oil Deal

2024-07-12 - The U.S. Federal Trade Commission’s request for additional information regarding ConocoPhillips’ $17.1 billion acquisition of rival Marathon Oil is likely to delay the transaction. Other recent energy M&A deals have faced similar “second requests” from the FTC.

Supreme Court Passes on MVP Appeal Challenging FERC’s Authority

2024-05-21 - The Supreme Court declined to take up a lawsuit against the Mountain Valley Pipeline, the latest in a series of legal maneuverings over a case filed by opponents of the pipeline.