Squeezing the European natural gas supply with winter approaching is a tactic in Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war with Ukraine, but the global consequences could mean a resurgence of coal. (Source: Hart Energy photo illustration; 42nd Street in Manhattan/Shutterstock.com)

Presented by:

A recent panel of three natural gas experts discussing the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent global energy crisis made two major points:

- The situation didn’t have to be this bad; and

- Without taking significant actions, it could get a lot worse.

The U.S. and allies responded to the Feb. 24 invasion with sanctions meant to exact a high price from Russia. But high prices go both ways.

“Western sanctions have a goal of degrading Russia as an energy supplier,” said Kevin Book, managing director of ClearView Energy Partners LLC, during an Energy Dialogues webinar hosted by Baker Botts. “That’s an interesting proposition because, if it succeeds, we’re looking at a potentially sustained shortage of energy.”

Tensions between energy haves and energy have-nots could strain alliances, he said, noting that some friendships between countries could be tested now that energy supply is no longer secure. To be blunt, Book said, when energy stops, the bets are off.

“The U.S. already has some sanctions fatigue from high prices,” he said. “Other countries in the world are getting there, too. High prices constrain opportunity. But empty tanks, empty pipes constrain reality.”

RELATED:

Global Tensions, Market Disruptions Likely Maintain High Natural Gas Prices

Part of that reality of European vulnerability relates specifically to the pipes. Russia provided about 40% of the EU’s natural gas supply prior to the war, most of it by pipelines. The volumes of LNG only constituted about 5% of European demand.

“Let’s say that the world had not had any pipelines and all gas was traded by LNG,” said Gabe Collins, Baker Botts fellow in energy and environmental regulatory affairs at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. “Gazprom would not have been able to withhold the equivalent of 5% of annual European gas demand in 2021. Those tankers would have just gone to China or South Korea or Japan, and whatever would have gone there would have been rediverted to Europe. Fungibility would have filled the gaps. Pipes break the fungibility.”

In effect, the infrastructure has allowed Russian President Vladimir Putin to weaponize natural gas.

“A pipeline is by far and away the best way to coerce,” Collins said. “It’s a bit like a knife fight where you’re tied to each other but, I think in this case, the Russians have a longer, sharper knife than the Europeans do and we’re seeing that play out in real time.”

If Russia wants to win on the ground in Ukraine, Book said, it may need to win on the grid in western Europe first. The EU’s target of reducing natural gas usage by 15% confronts that strategy.

Setting the stage

How could a global energy system suddenly shift from abundance and affordability to shortage and crisis? It wasn’t sudden. It took time and money—or, a lack of money.

“Under the surface, this crisis is underpinned by years of underinvestment, not only in gas and LNG, but also in traditional fuels, as we’ve diverted billions of dollars away from dispatchable fuels to intermittent greener sources,” said Renee Pirrong, director of research and analytics at Tellurian Inc. “And all the while, we’ve been ignoring energy security realities that have never really gone away.”

What we are experiencing in the wake of the war in Ukraine is a paradigm shift in the global price environment, she said. And get used to it. Structural changes to both supply and demand across all LNG markets—but more broadly, energy markets—will make this era of scarcity far more durable than the bull markets enjoyed in the past.

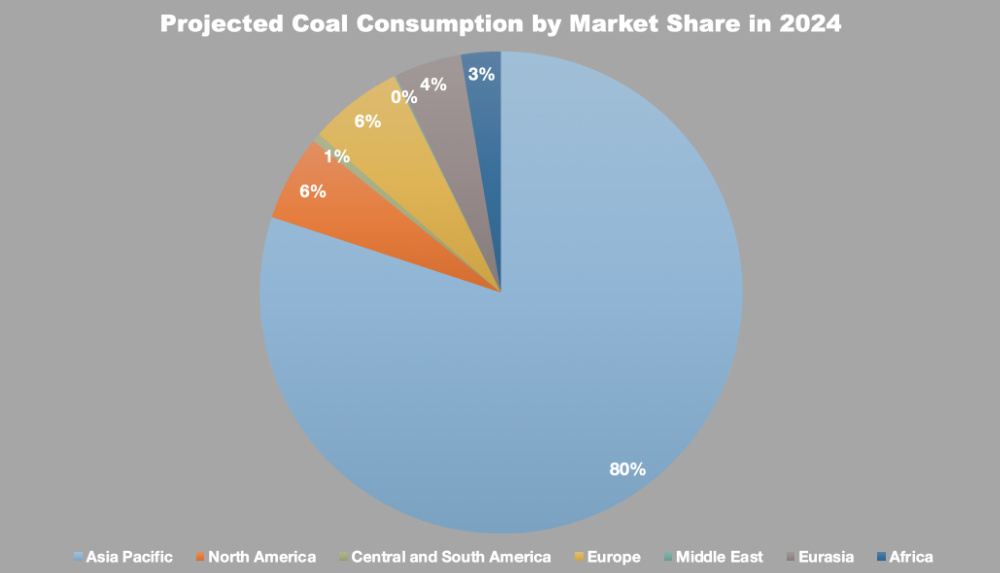

The structural changes begin with a demand shock. Asia has historically consumed about 75% of global LNG, Pirrong said, but by 2035, Europe could command a 40% share of the market. That couples with a supply shock, as sanctions removing not just LNG that Russia produces today, but huge volumes that would have come from Russian projects that cannot move forward without partnerships with western companies.

Near-term result: demand destruction.

“I think it’s ironic and a little bit sad that Europe, which has been, to some degree, lecturing the rest of the world against investing in gas, is now diverting LNG away from the markets that need it the most in the midst of this crisis, to shore up its own supply,” she said.

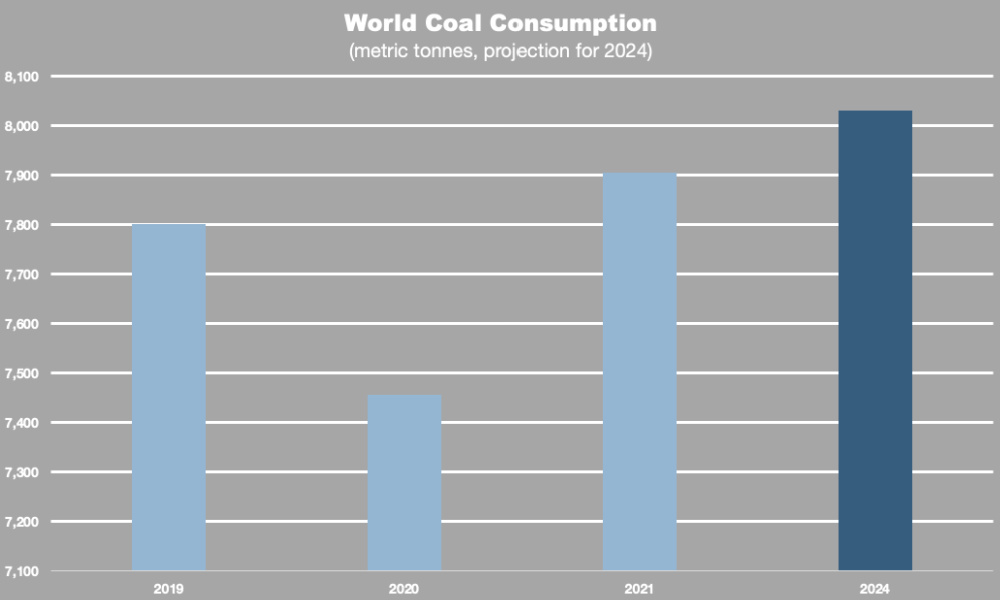

Long-term result: more consumption of coal.

“I think we will continue to see many countries return back to coal and we’re already seeing that happening in Europe,” Pirrong said. “European coal consumption has reversed its declines and they are now prolonging the life of those existing coal-fired power plants.”

From 2020 to 2021, the EU’s coal consumption rose 11.5%, according to the IEA.

Day of infamy

Collins cited three pivotal events that brought matters to a head in the European natural gas market.

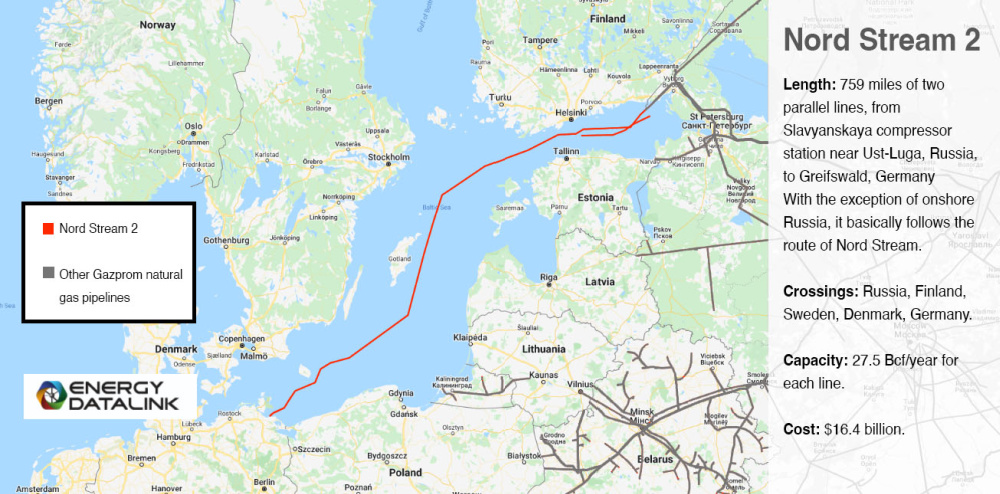

March 2014: Russia annexes Crimea, igniting a separatist war in eastern Ukraine. “These events should have accelerated Europe’s efforts to diversify away from Russian gas, but the largest consumers in Western Europe, instead, actually sought to deepen their reliance on Russian gas by continuing to pursue the Nord Stream 2 project.”

Mid-2021: Gazprom begins systematically withholding gas flows to Western Europe. “This now appears, I think, with the benefit of a bit of hindsight, to be an intentional preparatory step there was aimed at destabilizing European economies and political systems in advance of the invasion that the Kremlin, by that point, likely knew that it was going to launch.”

Feb. 24, 2022: Russia invades Ukraine. “I think it’s not overstating to view this as 21st century Europe’s day of infamy. I think it’s very reasonable, as well, to think that, as a byproduct to this violent revisionism, it’s probably reshaped European and, arguably, global gas markets for years, if not decades to come.”

Over the short term, Collins said, Europe will experience the roughest winter among industrialized countries in terms of tightness in the gas market and high prices. This will be the case, though to a lesser extent in northeast Asia and the U.S.

However, the outlook for developing countries is dire.

“It’s not simply having to pay more but still being able to have your heat and have your lights on and so forth,” he said. “It is much more likely to be a situation for hundreds of millions around the world to actually be priced out of these markets, with the attendant consequences that come with that.”

Crossroads

If Collins sees the European gas struggle as a knife fight with Putin, Pirrong has a different take.

“This is a romantic comedy,” she said. “You know, Europe realizes it always needed gas and it should have never said goodbye in the first place.”

In Book’s mind, Europe was of two minds even before the war.

“The issue we were looking at before the Russian invasion was Nord Stream 2, which looked to be a long-lived investment with significant endurance, never mind the transition discussion in the foreground,” he said. “I think there was always going to be fairly strong gas commitment in Europe, but one of the things that, in particular, the national security case for transition has grown stronger.”

The question is whether Western countries will commit to drilling. Book wasn’t sure, noting that Europeans tend to be squeamish about environmental concerns.

But what is ultimately at stake transcends the war in Ukraine or the natural gas market within the confines of the EU. It is all about decisions that will be made in world capitals over the next six to 24 months.

“To really put things in blunt terms, if there’s not an expectation of an affordable and secure gas supplies, at some point, reasonably here in the future, we’re likely to see additional coal lock-in,” Collins said. As far as Europe is concerned, that means extending the life of a coal-fired power generation plant that was scheduled to be shut down.

In China, India and Southeast Asia, however, it means that if a decision is made to build a coal plant, that facility is likely to operate for 40 or 50 years, with the emissions consequences that go with it.

That is not an inevitability. If the political will can be mustered, Collins said, there is an opportunity to signal natural gas producers that gas is a high-value energy transition fuel that will be needed for a long time. Such a signal could be what is needed to support capital investments and bring additional supplies to market.

Or things could get a lot worse.

Recommended Reading

Diversified to Buy East Texas NatGas Assets from Crescent Pass

2024-07-10 - Diversified Energy’s $106 million deal with Crescent Pass Energy comes during a prolonged dip in natural gas prices that some analysts expect to rebound as demand ramps up for LNG exports and power demand.

TotalEnergies Joins Ruwais LNG Project in UAE

2024-07-11 - French energy giant TotalEneriges joined the two-train 9.6 million tonnes per annum Ruwais LNG project in the United Arab Emirates with a 10% interest. The LNG project is expected to start sending out cargos in the second half of 2028.

Texas LNG, EQT Sign a 2-mtpa LNG Tolling Agreement

2024-07-24 - EQT will supply natural gas to Texas LNG, a 4- million tonnes per annum LNG export terminal planned for the Port of Brownsville, Texas.

Vitol Grows LNG Bunkering Fleet by 3 Ships

2024-07-07 - LNG trading company Vitol Group is emphasizing the environmental benefits of using LNG as a shipping fuel with the acquisition of three bunkering vessels to fuel ships.

TC Energy Completes NatGas Transmission System Sale

2024-08-16 - TC Energy Corp. and its partner Northern New England Investment Co. have completed the sale of the Portland Natural Gas Transmission System for US$1.14 billion.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.