Construction on Goodnight Midstream’s 45-mile Llano trans-basin gathering system, located in Lea County, N.M., was recently completed. The pipeline services long-term commitments from large producers with plans for expansion this year. (Source: Goodnight Midstream)

Endless mountains tower over the arid Permian Basin. Mountains almost a mile high. Mountains of water.

A football field covered with a foot of water is about an acre foot, a standard measure of water reservoir capacity. A mountain of water on that field 4,600 ft high represents the volume of produced water that could be coming out of the Permian Basin every day once oil production reaches its peak in the next few years.

Oil production could reach 6 MMbbl/d. Water cuts average 4 bbl to 8 bbl per barrel of oil. That is 1.5 billion gallons of water, or 4,600 acre feet, every day—and that is just the Permian.

To keep that in perspective, the capacity of Lake Mead east of Las Vegas is 26 million acre feet. But the point is made: After centuries of ignoring plays with high water cuts, and trucking what water is produced elsewhere, the industry is now fully immersed in produced water. By volume, the oil business is now the water business. And without major continuing capital investment in process and infrastructure for produced water, the shale bonanza will be sunk.

About a year ago, Callon Petroleum signed a new water supply agreement with Gravity Oilfield Services to support the company’s fracking needs in the Midland Basin. As the intensity of field operations increases in the Permian, companies are seeking greater reliability from a variety of sources including freshwater, recycled water or raw brackish.

“We have increased our recycling efforts meaningfully over the past year,” said Gary Newberry, Callon’s strategic adviser and former COO. “Our goal is to continue shifting more of our portfolio to sustainable water management solutions as they develop.

“Gravity has developed necessary infrastructure and source capacity in and around Callon leases,” he added. “They developed the system with the support of local surface landowners to support ongoing oil and gas development. This provides a secure source of water while continuing to develop reuse and recycling capacity to minimize the future use of freshwater and minimize disposal requirements.”

In late 2017 Callon signed an agreement with Goodnight Midstream, a large produced water infrastructure company, to build and operate a pipeline and injection system to handle a portion of the disposal needs from its southern Delaware Basin assets.

“The Goodnight Midstream system is in Ward County supporting our Spur asset development,” Newberry said. “The driver behind this concept was to remove excess produced water from the immediate area and transport those disposal volumes to the Central Basin Platform where they would not impact current operations. The system became operational in October 2018, and they continue to build out additional disposal capacity to handle our future needs. Goodnight Midstream has indicated that it intends to enhance the system capacity to service other operators.”

Callon already has begun using its new recycling-focused water management system in the Delaware Basin. “The enhanced system at our Spur asset is substantially complete,” said Jeff Balmer, senior vice president and current COO. “The new infrastructure consists of produced water pipelines across our acreage to our new recycling facilities as well as access the Goodnight Midstream receipt point for disposal away from our current leasehold.”

Enhanced recycling

Callon has been increasing its recycling operations to minimize water source requirements and disposal for both our Delaware and Midland basin assets.

“The Delaware recycling operations have been enhanced to provide as much as 50% of our water requirements,” Balmer said. “That significantly reduces the overall costs of water management and helps to reduce our environmental impact. Recycling as part of the water management program is something we regard as a vital component of our corporate sustainability efforts.”

Just as with hydrocarbon midstream, some producers prefer to own their own assets, while others prefer to have service providers handle the gathering and processing. Callon has used a variety of in-house and third-party water management.

“We are willing to invest in systems where necessary but prefer to be partners with companies that share our values and are aligned with our objectives,” Balmer said. “We prefer companies that support local land owners, build high-capacity reliable systems for supply, develop disposal systems with a focus on deep responsible disposal to avoid future drilling hazards and are committed to recycling and reuse as much as possible. Ultimately, it does become a tactical decision in many cases.”

Planning for water management has always been a critical component to successful oil and gas development, Balmer emphasized. “The most successful companies will make the appropriate investment or establish strategic partnerships. Callon has been active on both supply and disposal for many years employing longer term and backup agreements for supply, initiating recycling efforts in both the Midland and Delaware basins, and creating thoughtful disposal options that match the needs of the company but preserve operational efficiency,” he said.

Balmer was frank in stating the fundamental business discipline of water management. “By employing a proactive approach, we have been able to avoid having water management impact our operating margins or inhibit our ability to execute our operational plans. Thoughtful investments in water management can be a differentiator from an institutional investor standpoint and certainly function as a competitive advantage from an operational perspective,” he said.

Balmer added, “We are very pleased with the emergence of the new midstream businesses to support our needs. As companies continue to establish reliable infrastructure throughout the Permian Basin, we expect even higher levels of efficiencies to be achieved as these systems become further integrated and interconnected. We expect to see a continuous stream of thoughtful ideas brought to market and those that blend the right level of operational efficiency, cost consciousness and mitigation of environmental impact will likely be embraced by the industry.”

Beyond the Permian

In late 2018 Goodnight Midstream increased its revolving credit facility from $320 million to $420 million. ABN AMRO Capital USA and Wells Fargo Bank served as joint lead arrangers. Additionally, ABN AMRO served as administrative agent.

The increased facility will fund Goodnight’s continued growth in the Permian, Bakken and Eagle Ford shales as well as support working capital requirements. Texas Capital Bank, Regions Bank, East West Bank and Cadence Bank acted as co-agents. The syndicated bank group also includes Citizens Bank, BOKF and Iberia Bank.

It is also important to note that Goodnight is one of the few water operators that is active beyond the Permian. “One-sixth of all the water barrels in North Dakota come through our facilities,” Goodnight CEO Patrick Walker said. The company had more than two dozen in service and is building more.

“It was a record year,” he added. “In 2018 the Bakken set records for oil, gas and water produced. And that was with only 50 rigs running, down from 200 at the peak. That says a lot about the efficiency of our customers. They are drilling longer wells and making bigger fracs with just a quarter of the rigs. And we are not seeing any hesitation after the oil price turbulence of the last quarter of 2018.”

In the Permian Goodnight completed a connection late in 2018 to move produced water from the Delaware to the Central Basin Platform. The company also is building out two other systems each in the Midland and Delaware basins.

“The focus is mostly on the Delaware,” Walker said, “because the capital spending by the producers is so massive, and the water cuts are so high.”

In the Eagle Ford, Goodnight is building two systems, one in Atascosa County and one in DeWitt County, that are to be completed this year. Both have dedicated operators with contracted volumes. Across its customer base, Goodnight has contracts ranging from 10 years to the life of the lease, comparable to contracts gas processors have.

“We do redeliver some water but mostly for disposal wells,” Walker said. “We do not do any trucking. That is why pipes are essential. Most of our added value is in transportation versus trucks.”

Regarding water like oil

“We are very proud of the management team at Goodnight,” said Jason Downie, Tailwater Capital’s co-founder and managing partner. “They are among the best operators we have in our portfolio. They operate like a large-cap midstream company rather than a middle market private-equity-backed team.”

Expanding on that logic, he explained, “Until recently, the midstream water business was like the convenience store business: all about location and traffic. But to us, the water business looks a lot like the crude gathering business—it’s about 70% pipe and 30% truck. It’s not about traffic. It’s about market economics and best-in-class operations. If you look at the operations center for Goodnight, you could not tell if they are moving oil or water.”

That business approach, Downie added, is what enables Goodnight to pursue multiple projects at once. “The focus of our growth is driven much more by organic projects than by acquisitions. Producers are doing multistage horizontal drilling with multiple wells off one pad,” he said. The project economics require a comprehensive solution for the large volumes of both frac and produced water, or the project returns don’t work for the operator.

Another benefit of the operational success of Goodnight is as an exemplar for Tailwater’s investors. “Our limited partners have seen what Goodnight is doing, and they recognize the scale of this opportunity,” Downie said. “They read Hart [Energy] publications and know the wall of water in the energy sector is real. They see the value in minimum-volume contracts [MVCs] and acreage commitments, which are very similar to crude gathering.”

Downie elaborated that the company’s “approach to energy is full emersion. About 65% of our investment is in midstream, and we consider water an integral part of it.”

Beyond private equity, Downie sees a diversity of investors in the water segment. “There are many factors that investors take into account, and ultimately capital for water is likely to come from both private and public equity. It may not be a fit for all public energy businesses, but water assets should be very complementary to anyone already doing crude gathering. There are a lot of cost advantages to having multiple lines in the same ditch.”

Putting a historic perspective on the segment, Downie added, “Water has not been a focus for midstream businesses due in part to the lack of in-house geological expertise, which is more common in an upstream business. And, of course, historically there was rarely enough produced water to necessitate piping.”

Unconventional development, particularly in the Delaware Basin is changing that dynamic. “We have capacity for 600,000 barrels of water per day across the Permian,” Downie said. “Our anchor tenants are some of the best producers in the industry. Our MVCs, acreage commitments and fee-for-service contracts are very similar to crude gathering.”

The size of the water industry and contract structures make it very hard for traditional midstream to ignore the segment. Producers need the support.

It only gets bigger. “The forecasts for five years out are 5 or 6 million barrels per day of oil from the Permian, mostly on the Delaware side,” Downie said. “Those wells typically have a water cut of 4x to 8x. So we are talking about a water opportunity of 10, 20, 30 million barrels per day. Even 15% to 20% of that is a phenomenal business opportunity, and you don’t have to do it in many different basins.”

Pecos Star rising

In 2018 Solaris Water Midstream continued to expand its flagship Pecos Star System in the northern Delaware Basin, while continuing to expand and optimize operations in the Midland Basin. In June 2018 Solaris also completed an acquisition of the New Mexico brackish water supply business of Vision Resources. Vision retained its Texas operations, but its New Mexico business has been fully integrated into Pecos Star.

The acquisition included experienced staff as well as more than 15 MMbbl/year of source water permitted for industrial and oil and gas operations. Solaris also acquired access to significant additional sources of brackish water and more than 200 miles of water supply pipelines and associated rights-of-way.

The Pecos Star System in Eddy and Lea counties in New Mexico and Culberson and Loving counties in Texas provides oil and gas producers access to integrated source water, transportation, disposal and recycling. Pecos Star began moving water in May 2018, and by the end of the year, it included four Devonian saltwater disposal (SWD) wells and more than 140 miles of buried pipelines capable of moving in excess of 500,000 bbl/d.

Solaris also completed its first reuse project in the Delaware Basin and delivered significant quantities of brackish and blended reuse water to operators. Six more SWD wells are being brought into service in the first few months of 2019, along with an additional 80 to 90 miles of pipe, with all assets connected into the Pecos Star network.

“We are continually building,” CEO Bill Zartler said. “We talked about Phase 1, but phases 2 through 10 have just rolled one into the other.”

There are areas in the Permian Basin where Zartler said SWD wells are generally underutilized, while there is a need for additional disposal capacity in other areas.

“The Delaware Basin, as fast as it is growing, is short disposal capacity,” he said. “However, midstream companies like Solaris are investing capital as quickly as possible to keep up with the industry need. The remoteness and geology of the Delaware Basin also poses challenges, as most new disposal wells in New Mexico are drilled into the much deeper Devonian formation.”

COO Amanda Brock explained that Solaris has designed an integrated system, with multiple SWD wells connected to numerous operators by an extensive large diameter, bidirectional pipeline network. “Solaris is also focused on aggregating produced water on its system and treating this water for reuse. Our system is supported by long-term minimum-volume commitments and acreage dedications from top-tier operators, together with interruptible arrangements delivering produced water into the network,” she said.

“It is a complex hydraulic system with wells and recycling facilities,” Zartler confirmed. “We have multiple outlets for the produced water either at an SWD [well] or through one of our treatment and recycling facilities. Operators are beginning to use larger proportions of recycled water for their hydraulic fracturing operations. Our system is large enough and integrated enough to be able to handle spikes in demand and supply as wells are completed, flow back and are producing.”

To date, Solaris has focused on the Permian but keeps an eye on other unconventional basins. “In the Delaware we are like the dog that caught the car,” Zartler said. “We have evaluated the Bakken and the DJ [Denver-Julesburg]. Each have their own set of water-related challenges. Wyoming will be of interest as well. In the Eagle Ford water plays out fairly quickly.”

Expanding markets

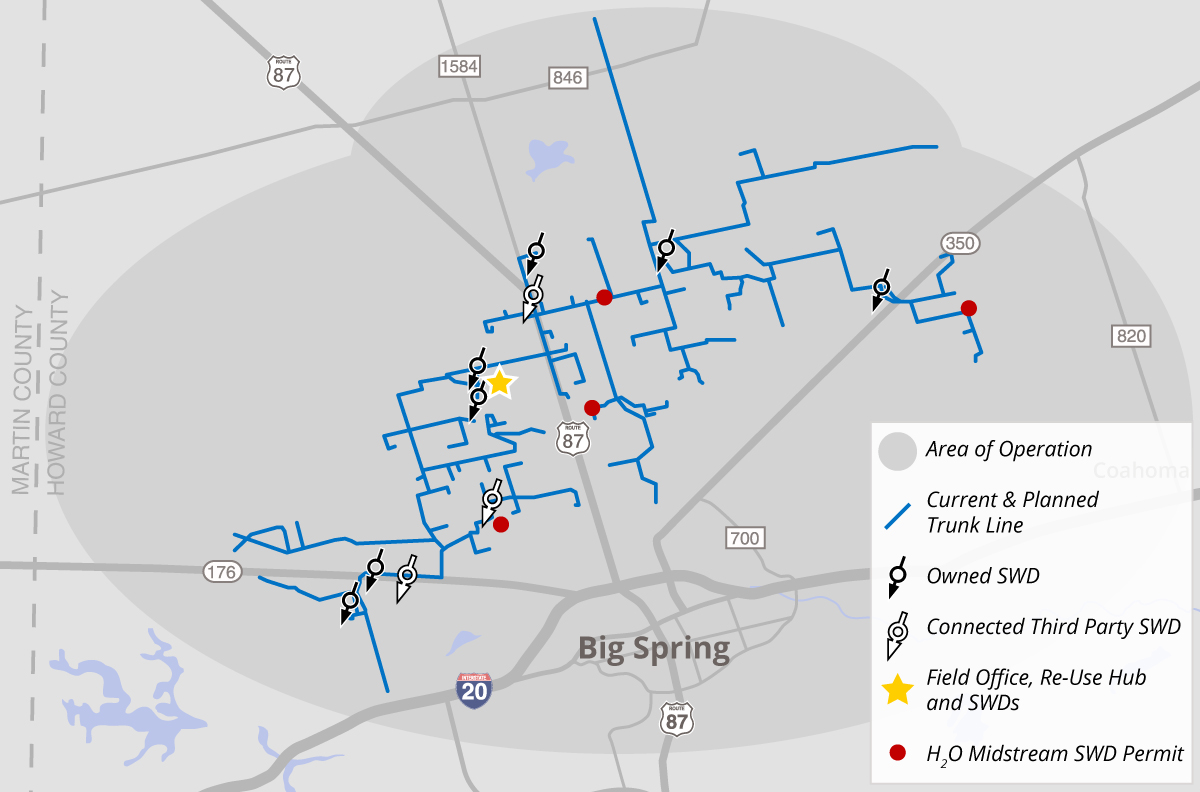

Thanks in no small part to its growth in size and scope, H2O Midstream was selected by the Texas University Lands management group to handle water across 167,000 acres in the Delaware Basin. University Lands manages the surface and mineral interests of 2.1 million acres of land across 19 counties in West Texas for the benefit of the Permanent University Fund.

“In 2017 we had just bought the Encana [water midstream] assets, so 2018 was a year of growth and also developing expertise,” CEO Jim Summers said. “We have had 18 full months of improving operational efficiency and flow assurance, implementing repair and maintenance programs, and decreasing downtime and costs.”

There was also significant growth in capital and clientele. “Last year we spent about half our capital budget on growth projects and about half on system upgrades that are all now in place. We also brought on five new customers and now provide various midstream services to Encana, SM Energy, Legacy Reserves, Surge, Sabalo, Apache and Grenadier,” he said.

The existing operations and customer base together with the University Lands arrangement represent two business streams for H2O Midstream, Summers said. The third will be acquisitions. “We have been involved in several sales processes throughout the Permian Basin,” he said, “and are hopeful of closing on at least one in early 2019.”

Capital structure evolves

To meet the total market for water flow will take billions of dollars in capital, notwithstanding the fact that the total market for all of midstream is more than $25 billion per year.

“Returns on water midstream around the industry have been comparable to crude gathering—in the mid to high teens unlevered, depending on the contract structure,” said Tailwater Capital’s Downie. “I am not aware of another manufacturing business in the U.S. with that potential in terms of quantity of capital and unlevered returns. Capital finds a way to get these things done. I don’t see a market where public capital lets private equity have that kind of potential all to itself for the next 10 years.”

Water also lends itself to public-private partnerships, Downie added. “Smart people will look at the volumes of water, see what might be taken for agriculture or human use, and see an opportunity there.”

He clarified that “the opportunity from our side is produced water. That problem has been brewing for 60 years. There are also opportunities in water for completions. E&P firms are buying water rights to have certainty of supply. They are going to find a way not to be arbitraged by the surface water owners.”

Looking across the sector, Summers at H2O Midstream sees the capital structure for water management evolving a little differently than hydrocarbon midstream has developed, mostly because water is not yet viewed by the industry as a true commodity with a developed market and pricing structure.

“Part of our business model is to treat water like a commodity rather than a waste,” Summers said. As the industry expands, he sees water becoming a full market commodity at some point, but that may still be several years away.

“At present we have a push and a pull of counterparties,” Summers said. “Some upstream operators have made the decision that water needs to be something someone else handles. Those are motivated sellers. At the same time, there is a fairly limited number of midstream water operating companies. There is also plenty of money participating from private equity. We have a view that water assets can support higher multiples when coupled with high-quality long-term contracts. We will certainly be buyers of those assets at a fair value—what that fair value is has yet to be determined.”

As the water segment matures, Summers reckons it will gain the attention of larger private-equity interests and possibly public markets. “In the short term, there is a lot of small and mid-size PE [private-equity firms]. They are nimble and they understand the story. A lot of capital needs to be deployed in the next few years,” he said. There is little argument about that, given the simple arithmetic of produced volumes even at modest forecasts.

“Private equity in the energy business, including water management, is prepared to take some risk and jump start the businesses,” Solaris’ Zartler said. “As the segment grows, we may see additional capital coming from infrastructure funds, sovereign wealth funds or perhaps partnerships that private capital has with some of the public MLPs.”

The more traditional exit strategies for private equity remain challenging. “We may also see some shifting around of assets within private equity,” Zartler added. “The public markets for energy are in a bit of disarray as is the MLP model for oil and gas midstream assets. There has been some S-1 talk by a few of the players in this new category and even a few filings, but those do not seem actionable today or in the immediate future.”

This is not to say there is limited interest in the sector. “There is plenty of capital to put things together, and there are a lot of water assets sitting in upstream operations that may move to new hands as the upstream operators focus their capital on drilling and completions. Lately producers have been keen to raise cash at favorable multiples.”

Public-private partnerships

Producers’ search for water for fracking was the original water challenge in the early days of the shale bonanza in the Permian. Those needs have more recently been overshadowed by vast volumes of produced water, but raw water needs have not gone away. One of the more innovative approaches has been purchase agreements or more formal partnerships with municipalities. Public-private partnerships are common in Europe and Canada and are becoming more familiar in the U.S.

“We signed a contract with Pioneer Natural Resources in August 2014 for 5 million gallons per day,” said Thomas Kerr, director of public works and utilities for the City of Odessa, Texas. “That was scheduled to start in 2015, but because of the economics in the oil industry, Pioneer deferred the start a year. We were at full implementation in August 2016.”

Odessa’s wastewater treatment plant is permitted for stream discharge, but the contract only specifies industrial discharge, which is clean but not certified for drinking.

“We are very pleased with the relationship we have with Pioneer,” Kerr said. “It has been a real benefit for the city. The contract is very straight forward. The initial rate is $6 per thousand gallons ($0.25 per barrel). That escalates after five years by $1.14 per thousand gallons ($0.05 per barrel). The contract runs for 10 years, with two five-year extensions at the discretion of both parties.”

Odessa produces a total of 8.5 MMgal/d. In addition to the direct contract with Pioneer, it sells some to agricultural users and indirectly to another Permian major, Concho Energy. That agreement is through the Gulf Coast Water Disposal Authority.

With current volumes placed, Odessa already is looking to improve its capabilities. “We are investigating reverse osmosis [RO] to manage the hard water we have naturally in the region,” Kerr said. “That would mean having a clean brine stream off the RO that we may be able to sell. By that time, we will have seen where these current supply contracts have gone.”

Officials at the adjacent city of Midland knew that Odessa had been selling treated water for years, said Laura Wilson, director of utilities for the city of Midland.

“They had a full biological treatment,” she said. “We have mechanical primary treatment, but we use a lagoon for biological treatment. Our output was 10 million gallons per day that was just going to irrigation. We wanted to do something better, so [we] put out RFPs [requests for proposal] for purchasing. We only got two or three proposals—10 million gallons per day is a serious infrastructure investment.”

Pioneer Water Management, a subsidiary of Pioneer Natural Resources, was the winner. The company offered to build a biological treatment facility. The city issued its notice to proceed in September 2018. The project is slated to be completed in October 2020.

"The actual cost of construction is $118 million, plus engineering costs,” Wilson said. “Pioneer is paying $120 million outright, plus a $7.5 million loan that we will pay back with water credits. The city is paying $4.25 million plus other improvements.”

The project will not be in service for another year, but Wilson is pleased so far. “I can say that talking to an oil company about wastewater treatment is very interesting. We feel very comfortable with Pioneer. It is a benefit to the city. At 98 cents per thousand gallons, we are not really making any money. We will just about break even on the operating costs. My utility fund won’t see much difference right away, more likely in the future.”

Midland’s total water processing capacity is 21 MMgal/d. The new secondary treatment has a capacity of 15 MMgal/d, of which Pioneer will be getting 11 MMgal/d, paying 98 cents per thousand gallons for the first 28 years. There are two 10-year extensions at a higher per-gallon rate.

Water treatment

The overarching issue in water management is the simple mass balance, said Enrique Proano, vice president of water management at Cudd Energy Services. “Even at 100% recycled water use, with every drop used for fracking coming from produced water, there will still be a huge excess in produced water. And that water will have to go somewhere. There will have to be vast investment in disposal infrastructure, whether that is for injection wells or transfer lines or treatment for other uses.”

Of all of those costs, the greatest cost is transportation. “The benchmark for economy is $1 per barrel per hour,” Proano explained. “So even if you are just trucking water 10 or 15 miles away, that is a full hour round trip. Our concept is to minimize transportation so operators can take advantage of redistribution opportunities within a few miles. We believe that is the where the market for water not used for fracking will settle, at least half of it, maybe more will be gathered, treated and reused within the immediate area.”

Cudd has two full sets of what it calls its mobile treatment plant as well as three smaller units in shipping container size. The units treat produced water to remove solids, hydrocarbons and dissolved solids to produce clean brine. The sludge is dewatered and the dry cake is disposed in licensed landfills. The big units can process 10,000 to 50,000 bbl/d.

So far Cudd has been treating water primarily in the Permian and Midcontinent. “Opportunities in the Rockies are large,” Proano said. “We have done quite a bit of work in the Northeast. If those areas should be reactivated, we would move back. There is also some potential in the Bakken.”

Hydrozonix has installed water processing capacity at 15 facilities with 500,000 bbl/d of installed capacity. That is 180 MMbbl/year and does not include its mobile treatment equipment.

“As our volume moves to 200, 300 and 400 million barrels per year, we are seeing the confirmation of a new business model,” said Hydrozonix President Mark Patton. “We size and build each facility for the producer. They own it and we operate it, which is really just routine maintenance because the systems are fully automated.”

Patton explained that while his firm and other processors can treat produced water on a cents-per-barrel fee basis under contracts of six to 12 months, “permanent facilities make more sense. It is better for the operator to buy the asset and depreciate it over the life of the facility.”

Hydrozonix signed its first contracts to operate and maintain producer-owned processing units late in 2017 and saw the approach gain traction through 2018.

Consolidation and seismicity

Onsite permanent water processing also might enhance the desirability of producing assets.

“In one case we have heard from both the buyer and seller that part of the value of the wells and infrastructure was the water treatment system we had built. After the transaction small neighboring operators contacted us about building water treatment for them too,” Patton said.

The company also has been innovating within the process, adding a slip-stream to the flow. “We use a 20% oversaturation with ozone with low pressure-drop static mixers,” Patton said. “That provides for a much lower pressure drop, only about 2 psi as compared to a 25 psi drop with an eductor nozzle.”

About 90% of Hydrozonix’s business is in the Permian, but there has been some work in the Bakken. “That tends to be more seasonal,” Patton said. “We are in discussions to go back. We are also talking with Scoop and Stack operators.”

Patton said the industry is “starting to see the overall midstream business as including water. The sector is likely to evolve as oil and gas midstream has, with some companies going public and perhaps rolling up other smaller operators.”

An additional prod is likely to come from regulatory scrutiny. “The Railroad Commission [of Texas] is looking into increased seismicity in Loving County and may be thinking about restrictions on disposal wells, perhaps limiting volumes and pressures (See sidebar below). We are already seeing similar things in New Mexico. This at a time when there is already a supply-demand imbalance. There is already more produced water than is needed for completion. Even if fracking was done with 100% produced water, there would still be a need for alternative disposal.”

For the present, there is so much variability in produced volumes and quality as well as in demand for completion. “Until all that stabilizes, it is hard to think of produced water as a commodity,” Patton said.

He also believes that in another five or 10 years, membrane technology will be sufficiently advanced to provide low-cost options for produced water at least at qualities for agricultural use.

“Today the crystallizers are energy intensive, and there needs to be membranes that are not fouled by produced water. There seems to be some potential in grapheme,” which will hardly put Hydrozonix out of work, Patton said. “We are looking at pretreatment technology to help limit the need for daily cleaning of membranes.”

SIDEBAR:

Induced Seismicity on the Decline

Induced seismicity has continued to decrease in Oklahoma as a result of limits placed on volumes, pressures and disposal formations for produced water injection. There were 194 earthquakes of magnitude 3.0 on the Richter Scale in 2018, down about one-third from the 302 in 2017. That is well off the peak of 901 in 2015 but still far more than the historical two or three before 2008 when significant well disposal began.

“In many cases this is a success story,” said Jake Walter, geologist with the Oklahoma Geological Survey. “There have been multiple factors. First is the decrease in produced water, as the industry has cut back operations because of the changing prices for hydrocarbons, and also shifting to shallower formations. There also has been a general shift away from drilling into formations with significant brines. And the Oklahoma Corporation Commission has limited wastewater injection.”

A clear cause-effect relationship has been established by the scientific community. “There is no question wastewater injection into formations adjacent to the crystalline basement has been augmenting conditions for earthquakes,” Walker said. “That is further supported by the decline in seismicity as injection has declined. The only questions now are around the specific mechanisms at depth.”

As those details are investigated by geologists, the larger question for the industry is “what are the pragmatic ways to extract these hydrocarbons without having to deal with huge volumes of water,” Walter said. “There are definitely such conversations going on, as there are explorations of what else to do with water other than injection.”

There have been experiments with irrigation or cooling water, or using waste heat for distilling. “This is the time to be having those conversations,” Walter said. “There will be earthquakes in Oklahoma from previous and current injections for decades.”

One challenge is funding. “Industry does provide some limited support for safe practices,” he said, “but there are limited opportunities for federal and state funding to develop risk-based decision making tools.”

Eye in the sky

A prime example of how quickly and dramatically water management is changing is the recent shift of Sourcewater from an online water market to a water information service. In late 2018 Sourcewater acquired the data and technology of Digital H2O, a subsidiary of consultancy Genscape. The move adds SWD analytics and data archives to Sourcewater’s geospatial water intelligence platform.

“In the Permian Basin, we now know where most fresh, brackish, produced and flowback water comes from, where it goes, who has it, who needs it and how much they are paying,” said CEO Josh Adler. “We can also show the flow rates and logistical relationships between every operator lease and every commercial disposal in Texas, and the capacity utilization of most saltwater disposal and injection wells nationally.”

Sourcewater was spun out in 2014 from Massachusetts Institute of Technology as the first cyber market for water. Today it handles more than 1,000 counterparties and billions of barrels of water. In the first few months of 2019, Sourcewater planned to complete the integration of the two platforms.

“We are also releasing a new technology for detecting and measuring frac water pits,” Adler said. “We have been doing frac pit detection quarterly for the past year. As of the end of January, we increased the frequency of our scans to every five days and will [have data] back to the beginning of 2016. The really big deal here is that we will be releasing the well pad detection at the same time. So we will be scanning the whole Permian Basin and detecting every frac pit, including size and water type, and every well pad every five days, and matching these to operator leases and surface owner records.”

The well pad detection is important, he added, because well pads predict new drilling activity three to four months ahead of drilling permit filings, which is how new operator activity is currently identified. “The satellite imagery analytics for detection of frac pits and well pads is a totally new data service and is patent-pending,” Adler said.

Current data can help mitigate the sharp variability in water management, but those data cannot change the realities of timing and volumes. “There is no way to build an optimal system,” Adler said. “If 10 operators all frac on the same day, there is going to be a massive demand. To build a system big enough to handle spikes in demand or supply, it would be too big to be practical, much less economical. The only way to manage water cost effectively is to trade. That is where we see our role as a market.”

While Sourcewater keeps close tabs on water flow, it does not track deal flow. “We don’t know of any water operators that are not being offered for sale,” Adler said. “We get asked all the time, but we are not a buyer.”

Adler does have some insight on the dynamics of the capital market in water. “There were a lot of investments made in 2012 through 2014, and PE backers are now seeing a window to monetize some of those investments. This is despite the recent decline in oil prices,” he said.

With a midstream eye, Adler sees the current discount of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) to Brent as mostly a transportation problem. “We are still waiting for pipe to come on. When it does, the spread between WTI and Brent, between Midland and Cushing, will go away,” he said.

Tempest over temporary hose

The growth of water management has not been without growing pains. In 2018 the county commissioners for Kingfisher County in Oklahoma issued a ban on using temporary water hoses, known as lay flat, for produced water on county roads on the grounds that the county could be held liable if there were a leak.

The industry quickly countered, led by the newly combined industry associations in the state. The associations got two rulings from the state Supreme Court confirming that the Oklahoma Corporation Commission (OCC) has sole jurisdiction in the matter. The commission asked the industry to recommend best practices that could be used to set standards. Separately, the American Petroleum Institute (API) has begun the process of setting formal standards. That process will take several years.

“Late in January the Oklahoma Supreme Court denied Kingfisher County’s renewed petition for rehearing,” said Cindy Hassler, manager of communications for Newfield Exploration. “We believe that with the denial of a petition for rehearing, this should finally conclude the case and permits for use of temporary lay-flat pipe will be issued by Kingfisher County.”

The dust-up over water has prompted the industry to accelerate codification of recommended practices for temporary hose used to move produced water. The associations were in the final stages of preparing their recommendations in late January. Some operators were proceeding on the basis of the court rulings; others said they were waiting for the commission to issue its guidelines.

“We did not want to go to court,” said Chad Warmington, president of OIPA-OKOGA. (OIPA-OKOGA is the oil and natural gas industry trade association created by the December 2018 merger of the Oklahoma Independent Petroleum Association [OIPA] and the Oklahoma Oil & Gas Association [OKOGA].)

He continued, “But under the county definition of produced water, they banned anything. It was an overreach, and at a time when the state is limiting injection to limit induced seismicity and also producers are trying to use more recycled water. We know there need to be best management practices, and we know everyone needs to follow them every time.”

And that applies to all surface owners, not just county roads. “The statute is clear,” Warmington said. “The commission has the authority to manage any cleanup and then go after the operator. We offered to indemnify the county against reasonable actions—not vandalism or negligence, of course—but responsible actions. It was very frustrating.”

The silver lining in all of this, Warmington explained, is that the industry is out ahead of an operational and environmental issue without there being a major leak, spill or other incident.

Prior to the OIPA-OKOGA merger, OKOGA filed its lawsuit against Kingfisher County and the OIPA filed briefs at the court in support of the lawsuit. The work done to create best practices began under OKOGA and continues under the OIPA-OKOGA banner.

“The Oklahoma Supreme Court previously ruled twice that the Oklahoma Corporation Commission has jurisdiction for produced water transfers using lay-flat pipe,” said Lloyd Hetrick, operations engineering advisor at Newfield Exploration. “It is up to us in the industry to continue to develop recommended practices because we will all be judged by the poorest actor. I would have told you the same thing a year ago, before the Kingfisher County situation, that the industry will continue to work on recommended practices because we recognize that lay-flat manufacturing, testing and use needs to be standardized.”

Hetrick noted that lay-flat hose is used in shale plays in other states, including Texas, New Mexico, North Dakota and Pennsylvania, without similar prohibition. He also noted that government entities in those other states have taken notice and are looking into the practice. All the more reason for the industry to be proactive and work together on a standardized practice.

“We never had much resistance anywhere until March 2018 in Kingfisher County, Oklahoma,” Hetrick said. “And the county commissioners just would not budge on the ban.”

The county’s stance is all the more vexing considering the investment that Newfield has made in water infrastructure and management.

“Our company has spent approximately $90 million in the Stack alone,” Hetrick said. “That is for SWD [wells], freshwater and produced water pits, recycling facilities and pipelines. We are proud of that investment. However, all that depends on the flexibility of lay-flat hose for connection purposes. And for that we need clarity from the OCC. Despite the state Supreme Court ruling, we are technically still in the prohibition, so we have asked the commission for guidance that will be clear.”

Newfield has built a multimillion-dollar water recycling facility in Kingfisher County, Hassler added, “and we have put in place lots of permanent pipeline infrastructure. We only use lay-flat for temporary and short distance connections.” She also noted that while Newfield and other large operators can invest in permanent transportation and treatment equipment, “the smaller companies may not have the same resources.”

To illustrate the importance of lay-flat to the industry, Hassler made an analogy to fire hydrants. “There is not one hydrant for every house, there is one on every block.” Firefighters use temporary hose for flexibility to get the water the last few hundred feet to exactly where it is needed.

“We feel we have been good community partners and good corporate citizens,” Hassler said. “It has been a tough situation, but I think it is going to be resolved.”

Hetrick is the lead for the industry working group in Oklahoma that is developing lay-flat recommendations to the OCC. Those recommendations are also likely to inform the API standards that are being developed concurrently at the national level. He is hopeful that one day those will be as common and accepted as are standards for motor oil: 10W-40 is an API standard.

References available. Contact Jo Ann Davy at jdavy@hartenergy.com for more information.

Editor’s note: During press time, Encana Corp. announced it had completed its acquisition of Newfield Exploration Co.

Recommended Reading

WhiteWater-Led NatGas Pipeline Traverse Reaches FID

2025-04-04 - The Traverse natural gas pipeline JV project will give owners optionality along the Gulf Coast.

DOE Identifies 16 Sites for Rapid AI Data Center Growth

2025-04-04 - The Department of Energy is requesting details on potential development approaches to establish AI infrastructure at select sites.

Energy Transition in Motion (Week of April 4, 2025)

2025-04-04 - Here is a look at some of this week’s renewable energy news, including Maverick Metals securing funding to accelerate commercialization of proprietary critical metals recovery technology.

Acquisitive Public Minerals, Royalty Firms Shift to Organic Growth

2025-04-04 - Building diverse streams of revenue is a key part of growth strategy, executives tell Oil and Gas Investor.

US Oil Rig Count Rises to Highest Since June

2025-04-04 - Baker Hughes said oil rigs rose by five to 489 this week, their highest since June, while gas rigs fell by seven, the most in a week since May 2023, to 96, their lowest since September.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.