Supporters say the proof of Rice’s argument is in the U.S., where carbon emissions steadily fell in recent decades as a torrent of cheap shale gas in the power sector displaced coal. (Source: Shutterstock.com)

From a converted karate dojo above a Pittsburgh liquor store, Toby Rice, a self-described “shalennial” who runs one of America’s biggest energy companies, has a plan to fix global warming and soothe European anxieties over fuel supplies.

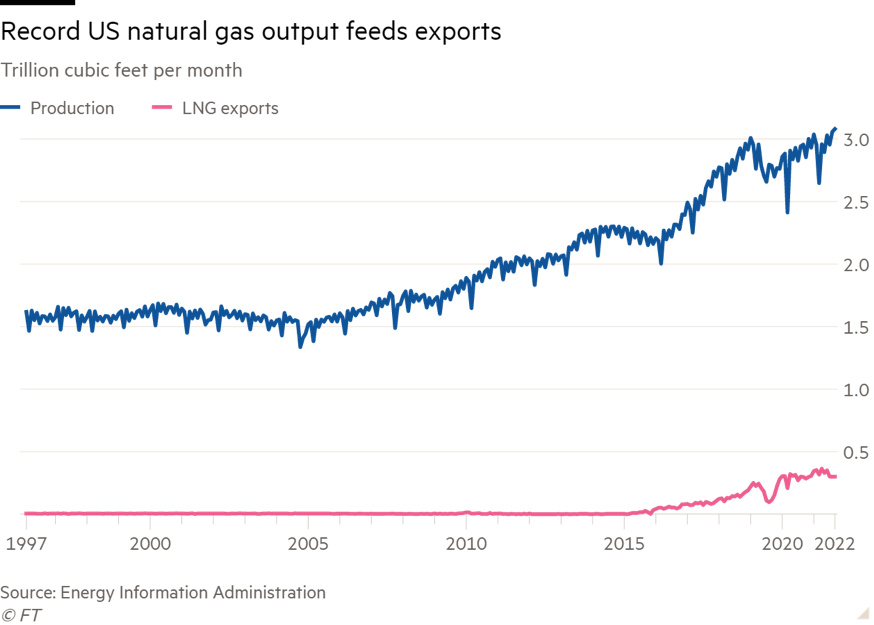

It involves lots more hydrocarbons—specifically, liquefied natural gas, the supercooled fuel that U.S. companies have been sending in record volumes across the Atlantic as Europe tries to break Vladimir Putin’s energy chokehold.

The world needs more American fossil fuels, according to Rice. “Unleash U.S. LNG,” reads the phrase on caps and shirts he hands to visitors stopping by the dojo. He contends doing so would enable American gas to kill off foreign coal and slash global emissions.

“Sending U.S. LNG to China and India is going to be the biggest decarbonizing thing we can do as a country,” Rice said.

Climate campaigners are far from endorsing his strategy, but it has become an axiom for a shale energy patch that now treats the 40-year-old Bostonian as something like a folk hero.

“The United States is going to be the biggest decarbonizing force in the world—but we need to unleash natural gas to address the biggest source of emissions, which is foreign coal.”—Toby Rice, EQT Corp.

Rice is CEO of EQT, a 134-year-old company few people outside the U.S. have heard of but which has become America’s largest natural gas producer, accounting for 5% of the country’s total—more than Exxon Mobil Corp. or Chevron Corp.

He has run the company since 2019 when he and his brothers—whose Rice Energy was bought by EQT for $6.7 billion in 2017—won a proxy war to unseat the board.

EQT’s gas is fracked from shale rocks across the Utica and Marcellus formations of western Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia—one of the most prolific hydrocarbon reservoirs in the world that lies beneath a region otherwise scarred by decades of industrial decline.

Europe’s crisis, coupled with a recovery in energy demand following coronavirus pandemic lows, has sparked a revival across oil and gas basins from Texas to the U.S. Northeast—one on which EQT has capitalized, with a market valuation that has risen 10-fold since mid-2020 to $15 billion.

The company last month reported almost $700 million in net profit between July and September, one of its best-ever quarters. It paid down debt, bought back shares and joined the S&P 500 index—a club befitting a company whose logo tops one of Pittsburgh’s tallest skyscrapers.

But Rice’s dojo is six miles away in the suburb of Carnegie. The tower—on which EQT is winding down a $10 million lease—was an example of the old EQT’s profligacy, he said, and the vibe was “too corporate.”

“And it’s in a city that has said that, ironically, they’re against fracking—which is like the biggest economic engine in this region . . . You want to be in places that want you,” he said.

Tens of thousands of contractors staff EQT’s well sites in the Appalachian hills around Pittsburgh. Most of its 700 full-time employees now work remotely, appearing as avatars on a virtual desktop that looks something like a Super Mario Bros landscape.

Rice and a handful of colleagues hold fort in the dojo, alongside a life-size mannequin of the superhero Iron Man, gorilla figurines and piles of a recent book by fossil fuel advocate Alex Epstein.

Mash-up portraits of American industrialists grace the walls and neon signs remind staff to “do epic shit” and “stay shaley.”

Rice himself decorated the windowless room at the back of the dojo with its wall of fake flora—the nerve center for his fracking business and campaign to address climate change by selling more gas.

“The United States is going to be the biggest decarbonizing force in the world—but we need to unleash natural gas to address the biggest source of emissions, which is foreign coal,” he said.

Supporters say the proof of this argument is in the U.S., where carbon emissions steadily fell in recent decades as a torrent of cheap shale gas in the power sector displaced coal, which releases about twice as much CO₂ as gas during combustion.

U.S. LNG export terminals have run at close to maximum capacity for most of the year, while production from gas wells is rising. But the scale remains far below what the U.S. could achieve with reforms to infrastructure permitting laws, Rice argues.

The sector “can grow production by 10 billion cubic feet a day”, he said. “That’s what we did in 2017 and 2018.”

That would be a 10% increase on current U.S. output and equate to about two-thirds of Europe’s Russian gas imports before the war. Rice said the U.S. could add the supply within 24 months.

In a sector that has become a villain for environmentalists, Rice’s willingness to take on critics—without doubting climate change or reeking of country club stuffiness—has made him a de facto spokesperson.

This year he wrote a nine-page letter to the liberal U.S. senator Elizabeth Warren, arguing against her efforts to restrict LNG exports.

“Toby . . . seems to relish conversations with skeptics and the far left and is committed to building a bipartisan coalition” to support U.S. natural gas, said Anne Bradbury, head of the American Exploration & Production Council, a lobby group that counts EQT among its members.

Republicans such as Mehmet Oz, the party’s pro-fracking candidate in Pennsylvania’s Senate race, have praised Rice, a registered Republican. But almost all the executive’s past political donations have been to pro-fracking Democrats.

Climate campaigners and some analysts have not been won over by his agenda, who say Rice is simply trying to lock in demand for a costly fossil fuel that will also need to be eliminated if the world is to hit its Paris climate targets.

“Toby Rice and others are known for creating this kind of false reality that people want to cling to,” said Mary Finley-Brook, an environment professor at the University of Richmond.

“The fossil fuel industry is running with people’s emotions. And they’re trying to act very fast, because they know the window is closing . . . until people will not put up with the climate crisis not being addressed.”

Soaring international LNG costs in the past 12 months hardly suggest the fuel can be a cheap decarbonizing agent for developing countries, argues Clark Williams-Derry, an analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, especially given the falling cost of renewables.

And even in crisis-stricken Europe, policy still favors cleaner energy—one reason why the International Energy Agency now expects global demand for gas to peak by the end of the decade.

The bigger problem is the US oil and gas industry’s poor record on methane, a greenhouse gas with far more heat-trapping potency than CO₂ in the shorter term. When the industry’s methane leaks are included in the calculation, LNG’s climate advantage over coal dwindles, researchers say.

Rice says shale operators are tackling the problem. His company is among those whose gas will be independently graded according to its methane performance. A U.N. methane monitoring body last week awarded EQT its highest rating.

Assuming the sector deals with its methane, Rice argues, it should be allowed to get on with displacing coal. “And if we’re not the cheapest, most reliable, cleanest form of energy? Guess what: see you later.”

For critics, this vision of natural gas as a “bridge fuel” between coal and cleaner alternatives is out of date.

“We don’t have time to get rid of coal and then spend the next 30 years getting rid of oil and gas,” said Mark Brownstein, senior vice president of energy at Environmental Defense Fund.

Yet the politics seem to be shifting behind Rice’s argument as European, Chinese and other importers line up to buy more American LNG. Investors who had been wary of fossil fuels are now calling for more oil and gas production—as is U.S. President Joe Biden.

“We could put gas on the doorstep of Europe for $12” per million British thermal units, Rice said—more expensive than U.S. gas prices, but a level well below what has been paid across the Atlantic in recent months. “People would be doing backflips for $12 gas in Europe.”

Editor’s note: Image of Toby Rice courtesy of EQT Corp.

Recommended Reading

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.