HOUSTON—Permitting reform is key to getting needed infrastructure built for natural gas, seen as the most promising existing route to lower emissions and reach net zero, according to the chief of a midstream company that handles about 30% of U.S. natural gas volumes through gathering, processing, transportation and storage services.

Speaking on Nov. 9 at Reuters Energy Transition conference, Williams Cos. CEO Alan Armstrong called permitting reform one of the main challenges and opportunities for the company.

“The good news is unlike a lot of issues that are very polarizing, there is support for permitting reform,” Armstrong said. “There’s support from the moderate Democrats. There’s certainly support from the Republicans.”

“But it is a very difficult issue, and it has to be done right,” he continued. “Our permitting processes are so far away from reasonable at this point in time, and we’re allowing NIMBYism [not in my backyard] to really stop our country in its tracks.”

Lengthy environmental reviews under the National Environmental Policy Act, Clean Water Act approvals and judicial reviews after objections by environmental and non-governmental organizations have halted pipeline projects. Developers say such projects are crucial to unlocking more gas supplies, including for export to countries needing to reduce coal usage to improve emissions.

Permitting reform could also make way for infrastructure needed for renewable energy projects or improvements to grids, which many say could face similar property rights or environmental objections. Inaction could lead to negative consequences, energy experts say.

Rising prices

The $1 or so increase in gasoline prices that U.S. drivers saw this year will be nothing compared to what will happen to utility bills in the future, Armstrong said, as the gas prices gets backloaded into utility rates. “It’s going to be loud and clear,” he said.

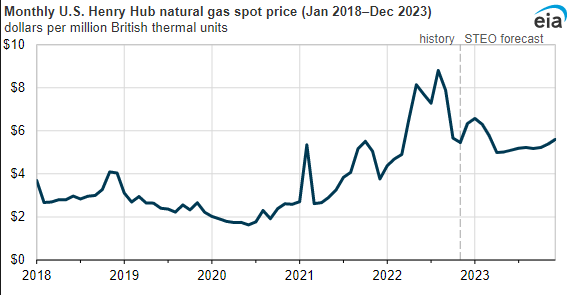

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecast this week that U.S. Henry Hub natural gas price will average $6.09/MMBtu this winter, its highest real price since winter 2009-2010. The forecast reflects natural gas storage levels 4% below average entering the winter withdrawal season and more demand for LNG, the EIA said. The price is expected to fall after winter as production rises.

“The reason that they’re so high here [now] is because the single largest source of gas and low-cost resources that we have in the nation is constrained by infrastructure and mightily constrained by infrastructure for projects out of that area that have had federal FERC [Federal Energy Regulatory Commission] certificates stopped in their tracks, in the courts and through the NGOs,” Armstrong said.

He used the Mountain Valley pipeline (MVP) as an example.

The natural gas market peaked this summer at 360 Bcf lower than the 5-year average, sending prices up, he said, before pointing out the 2 Bcf/d-Mountain Valley Pipeline should have been online two or three years ago.

“If we had that on for just half a year, we would have been in balance,” Armstrong said. “If we’d have had it on a full year, we would have been 360 Bcf a day provided that the price signals were strong enough to encourage gas development. Gas prices are plenty strong at the $3 mark in the Marcellus to drive gas development there. So, it purely is an infrastructure issue.”

Stuck, yet hopeful

The planned 303-mile pipeline, which would span from northwestern West Virginia to southern Virginia, is the only major pipeline under construction in Appalachia.

Equitrans Midstream Corp., one of the companies behind Mountain Valley pipeline, has said federal permitting reform is the best pathway to complete the pipeline in second-half 2023.

“There continues to be significant, bipartisan support for federal energy infrastructure permitting reform legislation,” Equitrans CEO Thomas F. Karam said in a news release Nov. 1. “However, despite current global events continuing to evidence the need for MVP to help the United States deliver energy certainty, security and independence, the same panel of judges in the U.S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals has again been assigned and appears hostile in an MVP-related permitting case. Further, there is timing uncertainty in the MVP permitting process.”

Construction of the long-delayed $3.5 billion pipeline started in February 2018.

Democratic U.S. Senator Joe Manchin had led an effort to enact permitting reform legislation in August as legislators debated the Inflation Reduction Act, which ultimately became law and made available a slew of incentives for clean energy development.

Permitting reform, however, did not get enough support to be included in the legislation. In September, a proposal by Manchin that sought to improve energy production in the U.S. by speeding agency review of certain clean energy and fossil fuel projects, including rapid expansion of transmission lines critical for better incorporating renewables, was pulled due to lack of bipartisan support.

Still, some remain hopeful—given the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

“Permitting reform, I think, can get done. It’s going to be difficult,” Armstrong said. “But I think there’s a lot of momentum between moderate Democrats and Republicans to get there.”

‘Politically vulnerable’

Permitting concerns also surfaced during a session on policy, leadership and governance in the transition as it rose to the top of a live polling question to conference attendees.

Everything needs permitting and government to get done, moderator Bill Brown, chairman and chief technology officer of 8 Rivers, pointed out.

“When you think about investable projects … if you can’t permit a CO2 pipeline or can’t permit a storage reservoir, then it doesn’t exist,” he said, noting it also impacts high-voltage transmission lines and raw material extraction.

The U.S. has vaulted to a leadership position given legislation passed, said Robin Millican, director of U.S. policy and advocacy of Breakthrough Energy.

“But of course, all of this is politically vulnerable,” she said.

With votes still being counted in key Congressional races as of Nov. 9, the final makeup of the House and Senate remains to be seen.

“We don’t yet know conclusively where the chips will fall because we will likely see runoffs in a few races,” Millican said. The most likely scenario is that Republicans will take a much narrower majority in the House than expected and control of Senate will hinge on three key states—Georgia, Nevada and Arizona. “Democrats basically need to win two out of three of those races tend to keep the [Senate].”

Looking ahead

What does it mean energy policy?

Millican doesn’t anticipate any legislative clawbacks, and if there are any, they won’t be successful.

“Certainly, I think there will be attempts, but any bill will need to overcome a veto proof majority, and the votes won’t be there for anyone that is inclined to do that,” she said. “So, I think in the next couple of years, we’re not likely to see any course corrections in terms of policy changes, but I think we will see a lot of oversight next Congress in terms of hearings, things like that. And to be clear, not all oversight is bad.”

Such oversight is needed to ensure programs are implemented correctly, guidance is issued quickly and large demonstration programs are on target, she added.

“Just from a pure political economy standpoint, a lot of these dollars will end up in red and purple states,” Millican said. “If you think about where carbon capture and hydrogen are most likely to go, where those projects are most likely to land, it’s places like Texas. It’s unclear that the political will will be there to want to change policy, even if there’s some potentially unhelpful rhetoric on the topic.”

Recommended Reading

Diamondback in Talks to Build Permian NatGas Power for Data Centers

2025-02-26 - With ample gas production and surface acreage, Diamondback Energy is working to lure power producers and data center builders into the Permian Basin.

Digital Twins ‘Fad’ Takes on New Life as Tool to Advance Long-Term Goals

2025-02-13 - As top E&P players such as BP, Chevron and Shell adopt the use of digital twins, the technology has gone from what engineers thought of as a ‘fad’ to a useful tool to solve business problems and hit long-term goals.

Aris CEO Brock Foresees Consolidation as Need for Water Management Grows

2025-02-14 - As E&Ps get more efficient and operators drill longer laterals, the sheer amount of produced water continues to grow. Aris Water Solutions CEO Amanda Brock says consolidation is likely to handle the needed infrastructure expansions.

AI-Shale Synergy: Experts Detail Transformational Ops Improvements

2025-01-17 - An abundance of data enables automation that saves time, cuts waste, speeds decision-making and sweetens the bottom line. Of course, there are challenges.

E&P Seller Beware: The Buyer May be Armed with AI Intel

2025-02-18 - Go AI or leave money on the table, warned panelists in a NAPE program.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.