It’s not every day that a research analyst is requested to write a cover story for an influential industry publication. But herein, I hope to add coverage that looks further forward to give a longer-term perspective on the opportunities and risks for the midstream segment of the ever-changing North American energy industry whose nexus is in Texas.

Toward this end, I have excerpted information that could have long-term impact on the midstream industry in Texas in general and the Eagle Ford in particular from Stratas Advisors’ current and former oil-side research. Other features in this supplement analyze bottlenecks in some of the other big unconventional plays.

We start by noting that the pace of U.S. shale development has been breathtaking. A bewildering price crash has yielded to an anxious period of ongoing-but-uncertain recovery. Global energy trade patterns are disrupted. New demand centers are rising. The U.S. is assuming a new role as a supply and export leader. Society is demanding lower impacts and cleaner energy. Hot money is chasing all manner of energy investments.

That has created numerous midstream bottlenecks as the industry adjusts.

The shale revolution is still ongoing. And because its effects are still spreading throughout the global energy industry, Stratas Advisors offers forward-looking research services to separate the future risks from the rewards, to assess the next opportunities and the potential pitfalls and to evaluate the investments and the returns. We hope our work in this publication shares unique and useful insights and lays out the processes by which Stratas Advisors, a Hart Energy company, conducts energy research and formulates these opinions and forecasts across the global energy value chain.

Four drivers

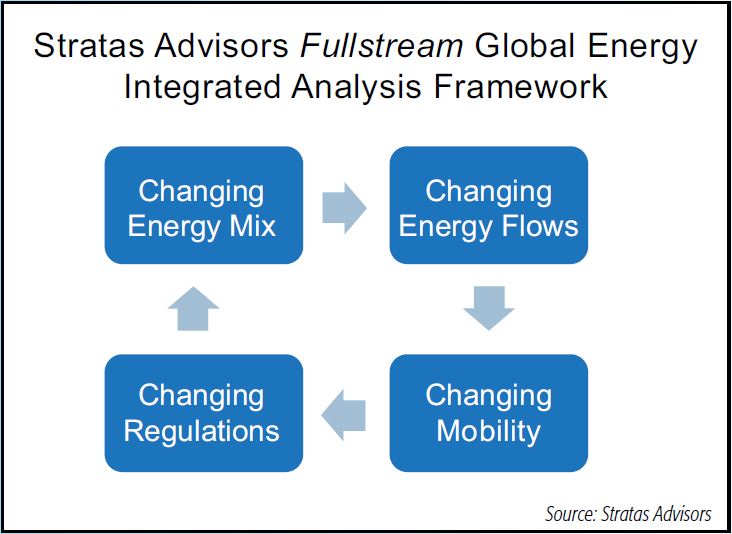

Changes in upstream supply and downstream demand are driving midstream change across the global energy industry. That reality directs our research analysts, who are located around the world, to provide clients with timely analysis and evaluation of the “fullstream” opportunities and risks impacting the global energy industry.

Stratas Advisors has identified four main themes relevant to the hydrocarbon supply side of the world’s energy value chain, but which also have proven utility for analyzing and communicating the dynamics in energy-consuming markets.

Midstream infrastructure, trade flows and pricing dynamics link the two ends of the value chain.

The themes are summarized below:

- Changing mix—A changing energy mix dawning with greater shale production, a growing importance on natural gas and a heightened preference for clean energy and alternative fuel is driving fullstream investment across multiple energy commodity value chains;

- Changing flows—Energy flows are coming from new supply areas, including the U.S., and are flowing to new demand regions with differing economic growth rates and energy intensities. Geopolitics and money flows are shifting with the energy economic poles as they rotate from the Atlantic to the Pacific Basin;

- Changing mobility requirements—A common shared affinity for mobility and electrification, digitization, autonomy, efficiency and green energy is evolving in all modes of transportation sector; and

- Changing regulations—An intensifying regulatory environment encompasses standards, regulations specifications, subsidies and mandates.

This fullstream framework guides us to produce our best and most valuable research, which must offer unique insight while staying ahead of the market.

Sulfur limits

Stratas Advisors’ view on fuel regulations and policies, for instance, allows us to analyze the affect energy mix, volumetric flows and export opportunities. Not all bottlenecks involve pipeline capacity.

For the Texas oil and gas industry, we see both opportunity and threat as a result of the ongoing reduction of sulfur emissions from the use of marine bunker fuel. The new targets, set by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) in 2016, set a sulfur content limit of 0.5% for marine bunker fuels. On behalf of our fuels and transport clientele around the world, Stratas Advisors researchers have been following the implementation and effects of the overarching MARPOL marine pollution reduction initiatives for years prior to that.

This latest sulfur emissions ratchet will take effect in world markets in first-quarter 2020. Our framework analysis shows the effects may soon ripple through the industry, and to Eagle Ford producers, midstream logistics, and Texas refiners.

The rules apply globally to between 4 million barrels per day (MMbbl/d) to 6 MMbbl/d of refined product demand. We see few compliance options, yet we believe compliance will be well enforced. Options include fuel switching to marine LNG or low-sulfur diesel, blending fuels, or onboard tailpipe emissions scrubbers. It is also uncertain how high prices may rise or discounts may fall to induce refiners to produce enough diesel or desulfurize bunkers.

All this will create a bottleneck. This change will propagate through the global industry. And the Gulf Coast midstream industry may need to accommodate both refinery crude and product slate changes to sustain operations in Corpus Christi, Texas Houston and across the region.

For instance, some may be able to switch from heavy high-sulfur crudes, or increase output of low-sulfur diesel, or blend and intensify processing of bunkers into more compliant fuels. These downstream changes would necessitate new or incremental midstream capacity for transportation, storage, segregation, blending and export options.

On the producing side, upstream producers could be persuaded by pricing to raise output of light sweet crude from the Eagle Ford, Permian and other competing resources. For Eagle Ford midstream operators in particular, upstream supply-side dynamics can also spur new gathering and takeaway infrastructure requirements.

Texas refining

In our 2012 multiclient Refining Unconventional Oil research report, we analyzed the 4 MMbbl/d of light-oil refinery expansions being talked up in the press. A bit of that has ensued with capacity up 860,000 barrels per day (Mbbl/d) since the 2011 baseline. Closures have also been seen in Hawaii, Alaska and elsewhere, a loss of 920 Mbbl/d of capacity. The strong refinery utilization we forecast also showed up as refinery utilization and is now averaging 91% vs. 86% then.

That represents a stealth 890 Mbbl/d capacity gain. Added together, the gains equate to about 2.1 MMbbl/d of equivalent new light-oil refining capacity. Yet U.S. field crude production rose 4.4 MMbbl/d from 6 MMbbl/d in 2011 to 10.4 MMbbl/d in May 2018.

The gap exists because of exports, which have undergone regulatory changes.

Oil could not be exported beyond Canada due to outdated federal export prohibitions implemented during the 1970s energy crisis. Regulatory changes in 2015 allowed U.S. crude exports to begin in 2016. U.S. crude exports have risen from almost zero to an average of 2 MMbbl/d in May, per the latest full month of U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) data. Refined product exports have also incrementally grown by 2.4 MMbbl/d over the same period.

Taken together and seen from a fullstream analytical perspective, the combined crude oil and petroleum product export flow equates to the gain in shale output! Roughly half of the incremental light shale oil output is flowing to offshore refiners while the other half is flowing to expanded U.S. refineries whose incremental products are also being exported offshore at upgraded higher values.

Looking ahead, we expect more of the same. Incremental crude production flowing to the U.S. Gulf Coast over the next decade will drive refinery expansion locally and expand refined product and crude exports in roughly equal measure.

Therefore, the midstream industry can compete for new business in refinery crude supply and product takeaway logistics, while U.S. field crude output increases through the next decade. Midstream companies including NuStar Energy LP, Buckeye Energy Partners LP and Howard Energy Partners are investing to export U.S. fuel products across Latin America.

Doubled crude exports

Based on our analyses of crude supply, petroleum demand and midstream logistics capacity, we believe U.S. light crude exports will double by the 2020s and be up to 5 MMbbl/d by 2030.

We believe the resources and available acreage within the productive oil-rich shale plays—the Eagle Ford, as well as the Permian, Rockies, Midcontinent and potentially the Bakken—are most likely to attract capital and incrementally yield 1 MMbbl/d to 2 MMbbl/d of light crude production above the current 11 MMbbl/d-range levels.

We take a more cautious view of U.S. refined fuel demand gains. Amid changes in the fleet, driving appetites, regulatory initiatives and alternative powered mobility, we do not see material movements up or down in transportation demand for petroleum over the next decade.

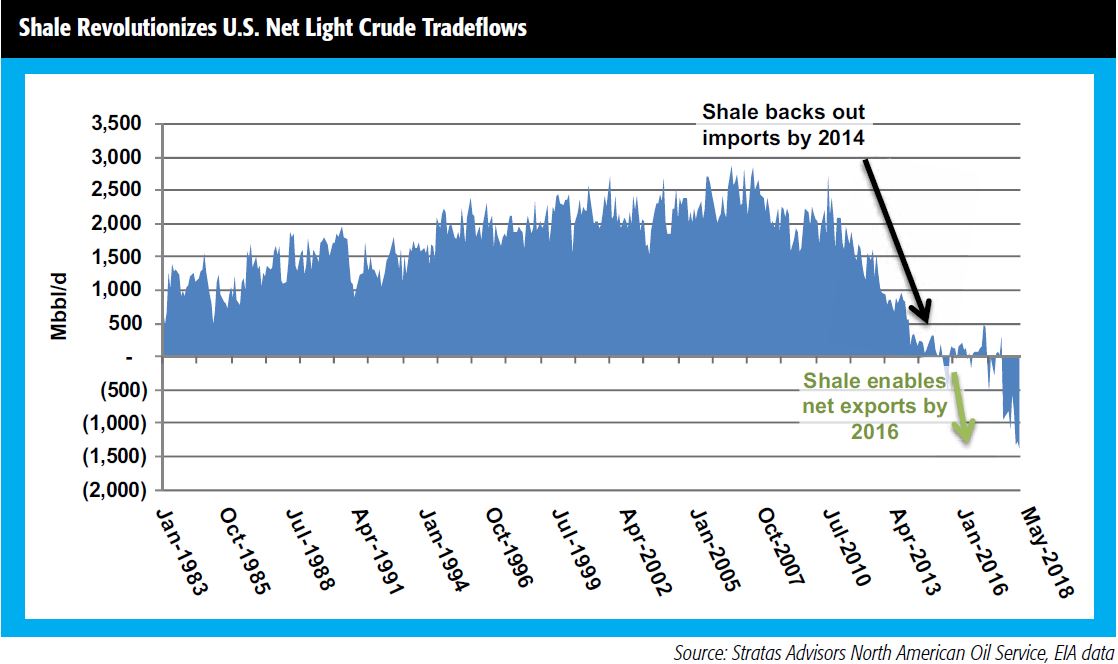

In that 2012 Refining Unconventional Oil report, we forecast that shale oil production gains could back out U.S. Gulf Coast light crude imports. We didn’t expect the speed at which that happened. Total U.S. imports of light crude were fully offset by light crude exports in late 2016.

Today, light shale oil exports have peaked in certain weeks of 2018 at more than 3 MMbbl/d and indicate robust net exports of light crude oil. This striking trade development is thanks to the changing energy mix and regulatory environment we see today.

We see offshore transfers or exports from Texas to the world’s other refining and consuming regions as key to helping production expand to 12 MMbbl/d to13 MMbbl/d in the 2020s without domestic supply overhangs, price discounts and existentially threatening shale economics. U.S. crude exports next decade may double and peak between 4.5 MMbbl/d and5 MMbbl/d.

Texas’ midstream industry will help the state’s industry become both the source and the gateway for higher light-oil supply for global refiners.

Caribbean crude

The offshore crude exports we forecast could include reboots at multiple simple Caribbean refineries. In Curaçao, parties are evaluating a potential restart of the 330 Mbbl/d Isla Refinery. At the former HOVENSA Refinery in the U.S. Virgin Islands, the current owner, Limetree Bay, plan to resume 150 Mbbl/d to 350 Mbbl/d of refining by 2020.

Mexico also plans to invest billions of dollars in up to three new refineries along the Gulf Coast that could refine as much as 750 Mbbl/d of light oil. Given various threats to ban hydraulic fracturing there, we believe a good fraction of the needed light oil will be imported from the U.S.

We see U.S. light crude nevertheless remaining at a discount to global light crude grades produced and priced elsewhere. That’s as long as U.S. refiners continue to run heavy-sour crudes after the IMO 2020 rules go in force. Price discounts in Alberta or from Mexico’s Pemex and Venezuela’s PDVSA could assure U.S. refiners kitted out for heavy crude will continue running it.

That should leave adequate supplies of light U.S. crude. We believe enduring discounts of Texas crude below global prices should help spur global offshore export growth.

By nation, Canada was the greatest U.S. crude importer in 2017. Canadian imports of U.S. light could grow if IMO-related crude shifting drives Canadian refiners toward sweeter, lighter crudes. Yet China was 2017’s second-largest destination for U.S. crude exports, and Asia as a whole was the greatest export region.

VLCC tankers

High-capacity very large crude carrier (VLCC) tankers are already enabling more U.S. barrels to travel greater distances at lower per-barrel costs. VLCC transits will likely be crucial in the global fullstream energy industry.

We see the main U.S. crude export gateway remaining along the U.S. Gulf Coast. The deepwater Louisiana Offshore Oil Platform (LOOP) near St. James, La., was built for offloading imports from VLCCs. The LOOP was recently revamped for bidirectional flow to enable VLCC export loading. The Capline Pipeline reversal is being developed to supply the LOOP with more North American crude for export or local refining markets.

A reversed Capline to the LOOP would be able to deliver Bakken and Canadian crude. Additionally, through the Diamond and interconnecting pipelines, Capline should also be able to provide LOOP exporters with available Permian, Eagle Ford, Rocky Mountain and Midcontinent Oklahoma crude, provided ample supply remains after any IMO-driven crude slate changes ripple through U.S. refineries.

The LOOP presently augments and competes against other existing crude marine export terminals. An additional Louisiana VLCC facility was proposed for deepwater near the Plaquemines, La., port on open season in the third quarter. Tallgrass Energy Partners LP announced the Plaquemines project in a press release detailing its plan to build a high-volume, segregated crude pipeline directly from the Cushing, Okla., pipeline hub to St. James.

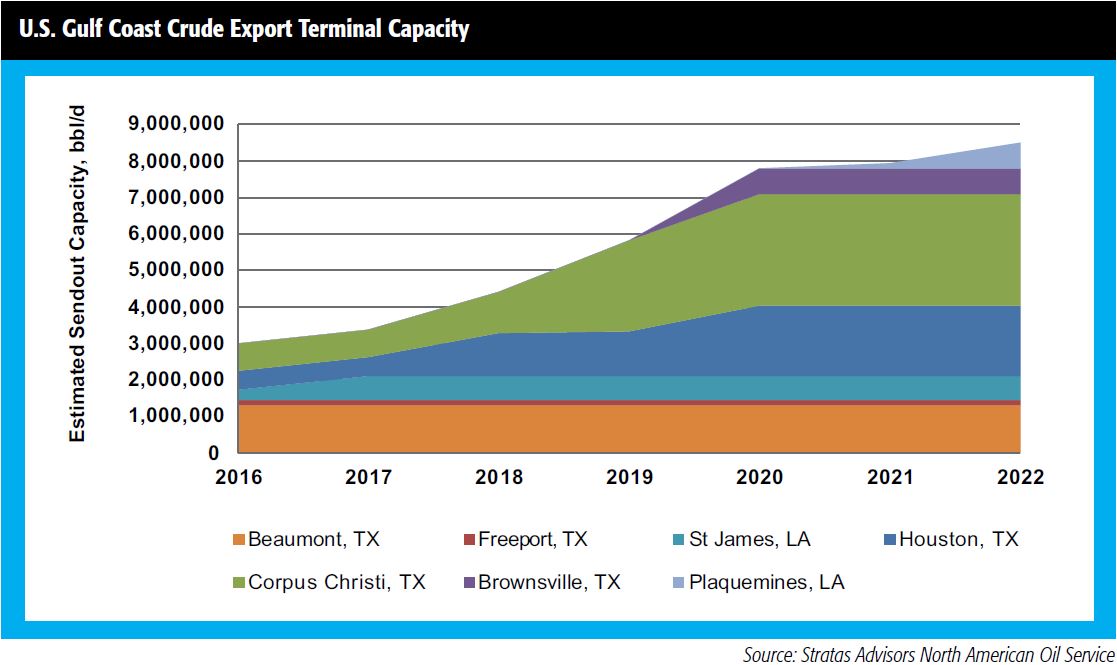

Furthermore, multiple proposals and investments are already underway to build out high-capacity VLCC takeaway from Texas. These projects will build on Texas facilities already loading smaller vessels or partially loading VLCCs with reverse-lightering operations. Dockside VLCC partial loading and reverse lightering are underway in Corpus Christi by Occidental Petroleum Corp. and the Houston Ship Channel by Enterprise Product Partners LP. Other VLCC operations in Beaumont and Freeport, Texas, are also either pending or operating.

All in, we estimate that the Gulf Coast, including LOOP, offers facilities to presently load 4 MMbbl/d of oil onto tankers ranging in size from intracoastal barges, to Suezmax, Panamax and VLCCs with capacities on the order of 750 Mbbl, 1 MMbbl and greater than 2MMbbl, respectively.

So while Louisiana has its LOOP and potentially another export facility at Plaquemines, we believe the home state of the Eagle Ford shale play, in particular, will strive to keep its boast that everything is bigger in Texas.

Several potential offshore projects are pending in Texas and will be based on deepwater moorings to fully load VLCCs in deep water without reverse lightering. We expect to see one or more of the VLCC loading projects finished. Projects are pending at the entry to the Houston Ship Channel (Enterprise Product Partners), in waters off Freeport (a reversal of the 2008-era import facility known as TOPS by Oiltanking and other partners), in waters off Brownsville (by Jupiter MLP) and at the 75-foot-deep waters at Texas’ Harbor Island or Ingleside at the Port of Corpus Christi (Buckeye Partners LP, Phillips 66 and Andeavor). San Antonio-based Andeavor is currently being acquired by Marathon Petroleum Corp.

Including all announced facilities, we estimate as much as 7.5 MMbbld to 8 MMbbl/d of crude export loading capacity could be online by the mid-2020s.

Earlier in the summer of 2018, we reported our expectations anticipating that oil majors and large integrated midstream firms will compete in this high-growth offshore export niche. To mitigate risks, we said we expected the formation of joint ventures (JV) to play a significant role in the space.

Several of the VLCC ventures bear this logic out. We see as most emblematic the 2018 announcements by ExxonMobil Corp. about reintegrating to fullstream operations amid the growing shale revolution. The supermajor is investing to grow Permian production, executing JVs for pipeline takeaway, and guiding analysts to model new refining or petrochemical investments to profit all the way to the export dock.

While the locations for VLCC crude export terminals may be relatively few, there are a number of ways for midstream operators of all sizes and capabilities to play this long-term trend. Oil exports will be dependent on operators and firms involved in the logistics of exporting light oil from one supply region to another importing consuming region. Key investments will likely be made in storage terminals, crude carriers, blending facilities, pipelines, marine loading terminals and docks, loading facilities, offshore mooring facilities and offloading facilities.

The volumes and infrastructure support needs will be significant.

The view back then

Since 2012, Stratas Advisors has tracked U.S. progress toward becoming a net energy exporter. That year, we saw a presentation on energy security at Rice University’s Baker Institute given by a former CIA official, John Deutch. He delivered a paper that quantified U.S. reliance on net petroleum imports at 52% of consumption in 2009. The paper proposed to lower that ratio to 29% by 2025 to reduce energy security risks via various switching efforts to lower oil imports and increase domestic gas and alternative fuel consumption. It even suggested imposing new refined product export prohibitions.

At the event, we inquired about the possibility that horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing could more rapidly revolutionize the supply side and even flood the market. Blank stares were the answers. A fullstream conceptualization was not in the picture. Since then, the Cushing hub has filled, U.S. crude discounts to global crude prices widened to the $30/bbl range, midstream operators invested billions of dollars, inland refiners filled up their coffers and OPEC saw its U.S. market share crater.

Since 2012, we have tracked that ratio and have seen U.S. import reliance fall into the 10% range. Within a shockingly few number of years, U.S. net petroleum exports enabled by the fullstream energy industry’s investment and operations have allowed the nation to nearly become a net energy exporter while internally providing almost fully for its entire energy consumption.

We see more progress along these lines in coming decades as the midstream adjusts to relieve the resulting bottlenecks.

Net imports

The available EIA data for the three months ended May 2018 showed U.S. petroleum imports averaged 10.1 MMbbl/d while exports averaged 7.45 MMbbl/d. That means the U.S. is a net oil importer by just 2.7 MMbbl/d. As U.S. crude output ramps to 12 MMbbl/d to 13 MMbbl/d in the next decade, the U.S. could directly become a net energy exporter. This could happen if about 1 MMbbl/d of net crude imports fall, either as a result of higher light crude exports or lower heavy sour imports; or if about 700 Mbbl/d of incremental production is exported as refined products and NGLs; and if another 1 million barrels of oil equivalent per day, as LNG or piped gas to Mexico, is exported.

We are that close. But new infrastructure and midstream investment will be required, especially in the Texas marketplace.

In this piece for the inaugural Oil and Gas Investor midstream supplement, I have intended to give readers a high-level, focused view of where the energy industry is heading as it relates to midstream opportunities in Texas in general and the Eagle Ford in particular. I stepped back from granular coverage of the latest bottleneck—the intrigue around infrastructure permits and the debuts of dueling open seasons. I have tried to provide fullstream visibility that draws from our global team of energy experts at Stratas Advisors.

Along the way, we hope to have shed ample clarity on the oil-related opportunities for the Texas midstream industry, both today and in the decade to come. I invite readers to contact Stratas Advisors for questions on the oil sector themes in this work or for additional views on natural gas, NGL and other branches of the integrated global energy industry.

Greg Haas is director of integrated energy for Stratas Advisors.

Recommended Reading

The EPC Market Keeps Its Head Above Water

2024-08-06 - While offshore investments are rising, particularly in deepwater fields, challenges persist due to project delays and inflation, according to Westwood analysis.

How Chevron’s Anchor Took on the ‘Elephant’ in the GoM’s Deepwater

2024-08-22 - First oil at Chevron's deepwater Anchor project is a major technological milestone in a wider industry effort to tap giant, ultra-high-pressure, high-temperature reservoirs in the Gulf of Mexico.

Chevron’s Gulf of Mexico Anchor Project Begins Production

2024-08-12 - Chevron and TotalEnergies’ $5.7 billion floating production unit has a gross capacity of 75,000 bbl/d and 28 MMcf/d.

Wood Mackenzie: OFS Costs Expected to Decline 10% in 2024

2024-07-30 - As service companies anticipate a slowdown in Lower 48 activity, analysts at Wood Mackenzie say efficiency gains, not price reductions, will drive down well costs and equipment demand.

E&P Highlights: Sept. 16, 2024

2024-09-16 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, with an update on Hurricane Francine and a major contract between Saipem and QatarEnergy.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.