The opportunity to cover — to constantly learn more, to write about, to participate in — the oil and gas industry is for this editor the culmination of near 30 years employment spent concerned with the constant interplay between technology innovation and production processes, i.e., how work gets done today in the industrial landscape of modernity. The word “culmination” fits because of the preeminence, depth, and breadth of the energy industry. Leaving aside food, clothing, and shelter, it’s the largest and most important industry in the world, and of course none of those basic necessities can be supplied without energy, the commodity of all commodities. Naturally following from this centrality is the fact that the oil and gas industry is at the heart of some of the most important issues of our time. You don’t have to look only to the convoluted politics of the Middle East to prove it. Russia’s energy policy and its foreign policy are nearly synonymous, for example. And the guarantee of freedom inherent in the US system of dispersed power centers comes at a high cost when the world’s leading economic power must compete with the unity of purpose demonstrated by sovereign wealth funds and national oil companies. It’s not just that wars are fought and people die because of the thirst for oil. Even when these dangers remain remote, the political economy of oil and gas can change the course of lives. For example, if not for the rise in unemployment following the first oil price shock of the 1970s this editor might never have enlisted in the military and had the opportunity to spend three years stationed in West Berlin, behind a wall that no longer exists. Finally, the industry’s breadth is seen in the range of disciplines at the command of its skills-driven workforce — from geology to petrophysics to petroleum engineering, and increasingly supported by automation and information technology. The chancellor of the University of Houston, speaking to the impending inauguration of its bachelors program in petroleum engineering, noted that the school was responding to the needs of the industry by including the study of business intelligence and master data management in its planned curriculum. It is also the case that engineers in oil and gas seem more acutely aware of how the world of finance impacts their work and decision making than is the case in other industries. The risk involved in drilling oil wells is qualitatively different than that particular to, say, deciding to build the IPod. Yet though the upstream oil and gas project remains to a unique degree an art dependent on the intuitive insights of highly skilled and experienced individuals it does share commonalities with other production industries. Anyone walking into an engineering department for the first time in the 1980s would have found manufacturers were just beginning to incorporate programmable logic controllers (PLCs) into industrial equipment design. Since that time, the PLC’s cousin, the remote terminal unit (RTU) has become the base device for oil field automation. Supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) as an aggregation point for data collection and dissemination is another class of solution that is found cross-industry with, however, important differences in how the market has evolved. SCADA in manufacturing and process production industries is today dominated by the major automation vendors to a degree not seen in the upstream space, where global dispersion and service needs have allowed niche players to survive. Given this emergent computer and telecommunications technology base, and also, for example, trends toward downhole sensing and production models to merge into a single system, upstream is beginning to share these other industries’ preoccupation with defined workflows and real-time decision making. And of course industries as diverse as manufacturing, process production, and downstream, midstream, and upstream oil and gas share the basic mechanical and electrical engineering processes of the bills of material, cross-section and plan view, wiring diagram, and the rest of it. In common is the real passion that can be engendered for working with steel and heavy equipment. Most basic of all is the shared project of bringing men and material together to accomplish some purpose, and the satisfaction of being part of a common endeavor that at the end of the day contributes to the common good, securing our employment and that of our fellows, as well as the prosperity of our families.

Recommended Reading

Exclusive: ‘Reality Has Hit,’ NatGas Not Just a Bridge Fuel, Landrieu Says

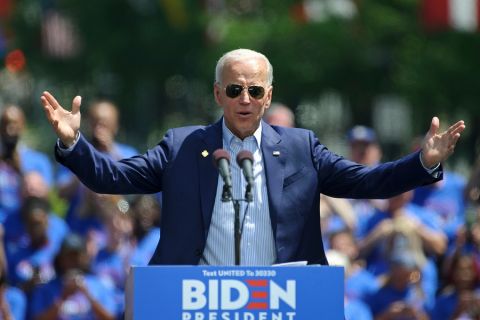

2024-04-11 - The Biden administration's LNG pause is "disappointing" and natural gas is a "solution to energy woes," co-chairs for Natural Allies for a Clean Energy Future Senator Mary Landrieu and Congressman Kendrick Meek told Hart Energy's Jordan Blum at CERAWeek by S&P Global.

Belcher: Our Leaders Should Embrace, Not Vilify, Certified Natural Gas

2024-03-18 - Recognition gained through gas certification verified by third-party auditors has led natural gas producers and midstream companies to voluntarily comply and often exceed compliance with regulatory requirements, including the EPA methane rule.

Hirs: LNG Plan is a Global Fail

2024-03-13 - Only by expanding U.S. LNG output can we provide the certainty that customers require to build new gas power plants, says Ed Hirs.

Pitts: Producers Ponder Ramifications of Biden’s LNG Strategy

2024-03-13 - While existing offtake agreements have been spared by the Biden administration's LNG permitting pause, the ramifications fall on supplying the Asian market post-2030, many analysts argue.

The Problem with the Pause: US LNG Trade Gets Political

2024-02-13 - Industry leaders worry that the DOE’s suspension of approvals for LNG projects will persuade global customers to seek other suppliers, wreaking havoc on energy security.