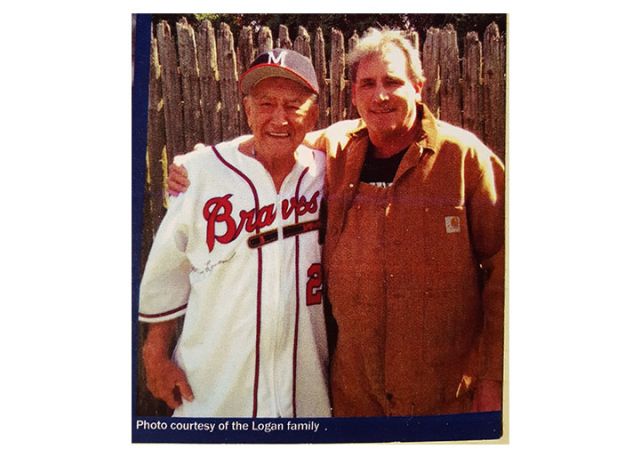

Pipeline construction veterans Johnny (left) and Jeff Logan. (Source: Logan family)

[Editor's note: Opinions expressed by the author are his own.]

My wife Janet and I have over 60 years of experience in the energy industry and often discuss the business opportunities. An April 28 article in the back pages of the Houston Chronicle touting the demand and relatively high salaries for welders grabbed our attention because welding is the heart of pipeline construction. One bad weld can cause enormous problems.

Ever wonder what it’s like to work on a large-diameter pipeline? I’ll try to answer that with the help of my friend, Jeff Logan, a native of Milwaukee who is a second-generation pipeliner.

First, let me digress and explain our history. Summer nights, Janet and I love to watch baseball. We happened to catch a Milwaukee Brewers game as they inducted Johnny Logan, the now-aging star shortstop of the 1957 World Series champion Milwaukee Braves, into the team’s Walk of Fame. The Logan family still lived in Milwaukee where Logan often attended Brewers’ games.

I immediately perked up because I had a bond with Johnny, a native of Endicott, a small city in upstate New York where I was a reporter for several years. The four-sport letterman remained a legend in his hometown because he was the local boy who made good. In 1987, I interviewed him at an old timer’s game in Washington, D.C. where we talked about baseball and life in Endicott, a community best known for being the headquarters of the now-defunct Endicott Johnson Shoe Company (where both Johnny’s parents once worked) and where Thomas Watson founded IBM.

Move forward to 2013. This time around my curiosity led me to an internet search and lo and behold…Johnny was a pipeliner in his post-baseball career including working as a welder’s helper during construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline in the 1970s. I needed to learn more and sought a second interview with Johnny. After many calls I connected with Jeff, one of his three sons. After convincing him that I was not a memorabilia hound, he agreed to try to arrange the interview for several reasons: his dad had a good story to tell, it would take his mind off his failing health and likely be his last interview.

We talked in between his thrice-weekly dialysis treatments about Endicott, baseball and pipelining. He remembered the extreme working conditions in what was still frontier terrain, often 16-18 hour days in minus 40-degree temperatures in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by gangs of hard-working, equally hard-drinking and hard-gambling co-workers (though the four-time National League All-Star professed to being neither a drinker nor a gambler). He said the only real excitement came from hungry bears sniffing around for bagged lunches.

Figuring time was short, I sent a FedEx of the magazines with article and cover photo to Jeff. Johnny died a few days later, on Aug. 9 at age 87 with his sons at his bedside. At least, Jeff said, he had a chance to read that last interview.

Jeff had followed in his dad’s footsteps as a welder’s helper. He is 60, owner of a small, profitable trucking company that he started with his oil field money. He’s an affable fellow, who seems content with where he is in life and has fond memories of pipelining. In fact, if he was a few years younger, he might still be working somewhere on a spread.

So, Jeff, how your dad, who had no welding experience, get started as a pipeliner?

“Dad packed a bag full of baseball memorabilia and sort of went [based]on his name though a lot of pipeliners aren’t sports fans. He went to Anchorage and was fortunate to get hired on. He met a journeyman who came from a big pipeline family with a lot of pull in the pipeline industry. We got lucky that in Alaska he fell in with the right people who were influential in the pipeline business which also helped my career and helped us pursue work in the lower 50 states. It’s influenced by people you do know.

“Dad was pretty fortunate he was on a testing crew. Sometimes they would be out 24 hours a day because they were on standby in case of a problem with the pipe,” Jeff told me.

RELATED ARTICLES:

- Pipeline Construction Projects: In Constant Demand

- Relationship Building Is Key To Trans Mountain Expansion

Johnny spent much of 1976 (when construction began) to 1979 (when construction finished) in Alaska.

But the money was good ($11.60 an hour, time and a half after 40 hours, he said), so was the food, and there were no living expenses with everyone living in barracks. Finally, after years of struggling, he could now support his family. He said he loved helping construct the pipeline which was America’s energy lifeline for years to come.

“Because of our family’s financial position, dad sent the whole check home to my mother. I don’t even think he cashed them, to be honest with you,” Jeff said. “He stayed up there as long as they needed him. I don’t believe he ever came back for a visit. He was in his 50s when he went up there. I know from getting older myself, it must have been pretty hard.”

Jeff’s own pipeline career began in 1980 with construction of Northern Border Pipeline in South Dakota. Johnny hadn’t been back from Alaska for long and he wasn’t very impressed with his son.

“I wasn’t doing too much. I went one semester to college and decided it wasn’t for me right at this time. My parents said they gave me a shot and if I ever wanted to go back, I was on my own. So, I was hanging around being a kid, enjoying my freedom. Then the union called, Pipeliners Local 798, and said there’s work in Watertown, SD. Dad paid me up (union dues), and said, ‘You’re not working, you’re not doing anything, you’re coming with me.’

“That’s when it all started with me, but I sort of liked it. The money was good, I was outside my state seeing some of the country, meeting some good people in a pleasant county, spending quality time with my dad too. We rented a two-bedroom house trailer and stayed about six months. My mother would visit to provide some company, spend time with my father, and see both of us earning a good living,” Jeff said.

Meanwhile, Johnny was nearing 60; the family’s finances were more secure thanks to his work on the Alaskan pipeline and a few spreads in the upper Midwest. He’d had enough of pipelining, but not Jeff. He worked for a while in Bismarck, ND on a 48-inch pipeline. A short layoff followed, then came a call for a pipeline job from Cortez, Colo., [JS1]to Albuquerque, N.M., which became a family affair of a sort.

“My little brother got a four-year baseball scholarship to University of New Mexico. Dad was then pretty much semi-retired; they were doing fine financially, so he came down with mom and spent the summer watching my brother play ball. I was working on the pipeline so the whole family was in Albuquerque, like home away from home.”

The money was pretty good, too.

“It was $18 an hour at least for a helper, up to about $22, depending on what state you went to. In New Mexico, I was working 75-80 hours a week. Everything over 40 hours was time-and-a-half, so it was a heck of a living for a young kid. It sort of spoils you when you come back to reality, look for a job and they want to pay you minimum wage because you don’t have experience. One year in the mid ’80s we only had 16 weeks of work and you filed for unemployment every winter. I called the union hall and was told there was two weeks of work in Ft. Lauderdale. I needed two more weeks to get my unemployment, so I went down there and worked on some little project. At $13 to $14 an hour they didn’t pay very well in Florida, even though it was union.”

Work was sporadic for everyone, not just Jeff, throughout much of the decade Jeff was pipelining. The domestic oil and gas business was paralyzed by the seemingly endless downward spiral of energy prices. The love of a girlfriend also curtailed that vagabond lifestyle. A four-month job in Michigan’s upper peninsula was his last pipeline work around 1990, and this provided him with some needed financial security. He had learned by now that one of the vagaries of pipelining is its seasonal nature.

“It almost seems like you end up starting all over again every year. I took more money home with me than typical pipeliners because they would spend a lot of money when they’re making it. I learned that from my father. But it seemed like I would have to borrow money to get back out the next season and go to work again. I spent it all during the winter to survive.”

Preferring a year-round job, Jeff worked for a soft drink bottling company, then the Postal Service, before finding work with a construction company that eventually led to him starting his own business.

As our conversation neared an end, Jeff spoke of some of the challenges of pipelining.

“Once you get on the job, it takes two or three days to get into your routine. As far as packing up your car heading out somewhere not knowing where you are going, trying to find a place to live, all those uncertainties, you saw it all come together once you got to your destination and knew you were hired on, it seemed like everything fell in place, for me, anyway.

“It was pretty easy once you got there because you knew what you would be doing, working seven days a week, maybe Sunday off to do your laundry or go to the grocery store and get your supplies for the following week. So it was pretty much a routine.

“Our job was to take care of the welders. Once you got to know your welder’s routine, we were just like their go-to guy; anything they needed, that was our job. Whatever they asked for, we tried to make their job as easy as possible. One year we were grinding beads for the welder to hold the pipe together [before] the finish welder came by. We were called a weld gang and would have three helpers because we were so busy. We were grinding 200-300 beads a day non-stop, 40-60 maybe 80 welding rigs coming up behind us. It was our job to put the whole thing together to keep the guys behind us busy. It was pretty brutal work. We had one crew compared to 50-60 crews behind us. So, we were humping all day long. It was pretty challenging, but it was a good experience. I enjoyed it,” Jeff said.

Today, pipeline workers, especially welders, are in high demand. Jeff recommends pipelining as a good job for a young person.

“As long as the work is steady, you’re making a living, I would say absolutely. Back in 1982 I was back home and needed something stable. There was a job in North Dakota, I was 22 and my mother didn’t want me to go alone, so I recruited a buddy from Milwaukee. We did dad’s old trick. I took some autographed baseballs and went to the trailer where you signed up. I gave the foreman a couple of my dad’s baseballs, said I had a friend outside, and we got my buddy hired.“

“There are opportunities for advancement,” he went on to say. “You can go as a journeyman, or work on the line and work up to welder which is a respectable position with a living wage. These are real-life experiences instead of reading it in a book. Not a lot of people have the chance to see the country; it was like a working vacation. I wouldn’t trade those days for the world. I have life-long memories from just those five or six years. Some people decide to go to school; I didn’t want to live life through a book or a classroom. I’d rather experience it first-hand.”

Jeff Logan concluded, “Pipelining was really my Major Leagues.”

Recommended Reading

Oil Broadly Steady After Surprise US Crude Stock Drop

2024-03-21 - Stockpiles unexpectedly declined by 2 MMbbl to 445 MMbbl in the week ended March 15, as exports rose and refiners continued to increase activity.

Imperial Expects TMX to Tighten Differentials, Raise Heavy Crude Prices

2024-02-06 - Imperial Oil expects the completion of the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion to tighten WCS and WTI light and heavy oil differentials and boost its access to more lucrative markets in 2024.

US Gulf Coast Heavy Crude Oil Prices Firm as Supplies Tighten

2024-04-10 - Pushing up heavy crude prices are falling oil exports from Mexico, the potential for resumption of sanctions on Venezuelan crude, the imminent startup of a Canadian pipeline and continued output cuts by OPEC+.

Exxon, Vitol Execs: Marrying Upstream Assets with Global Trading Prowess

2024-03-24 - Global commodities trading house Vitol likes exposure to the U.S. upstream space—while supermajor producer Exxon Mobil is digging deeper into its trading business, executives said at CERAWeek by S&P Global.

Majors Aim to Cycle-proof Oil by Chasing $30 Breakevens

2024-02-14 - Majors are shifting oilfields with favorable break-even points following deeper and more frequent boom cycles in the past decade and also reflects executives' belief that current high prices may not last.