Eastern-based Libyan forces commanded by Khalifa Haftar launched an offensive last week to take control of Tripoli, the capital, plunging the OPEC country into a new round of armed conflict.

Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA) faces fierce resistance from rival military groups, and oil prices have risen above $70 per barrel on fears of new losses to Libyan production.

As a major supplier of oil and gas to Europe and starting point for migrant flows into Italy, much is at stake if the country slips into further turmoil.

How Did We Get Here?

Libya began fracturing in 2011 when local groups took up arms against leader Muammar Gaddafi amid the Arab Spring uprisings but also turned against each other.

Gaddafi ruled Libya with an iron fist for 42 years, keeping control over its various tribes and clans.

As rival militias swelled and Islamist militants gained a foothold in Libya after Gaddafi's fall, Haftar, a former general in Gaddafi’s army, presented himself as the man who could crush the extremists and bring the militiamen to heel.

But Haftar is a deeply divisive figure. His military campaigns have faltered and his critics accuse him of seeking to return the country to authoritarian rule.

The Battle For Libya’s Oil

Once Africa’s third-largest producer with output of 1.6 million barrels per day (MMbbl/d) before the revolution, Libya’s oil output slumped to just 150,000 bbl/d in May 2014. Current output is about 1.1 MMbbl/d, according to Reuters estimates.

As the backbone of its economy, control over oil has been at the core of the unrest that followed Gaddafi’s overthrow in 2011, a slow-burn conflict that sees occasional eruptions of intensive fighting.

Factions have used oil facilities as bargaining chips to press financial and political demands. Fields and ports in Libya’s east were blocked throughout 2013-2016.

In 2016, Haftar seized most facilities in Libya’s east and this year his forces swept through the south, taking control of the major El Sharara and El Feel oil fields.

Islamic State lost its Libyan stronghold of Sirte to local forces backed by U.S. air strikes at the end of 2016, but some of the facilities the militant group attacked remain unrepaired.

Who Controls Libya’s Oil?

The simple answer is the National Oil Corp. (NOC), headquartered in Tripoli. It is the sole entity controlling oil and gas field operations and the only marketer of Libyan oil abroad.

But since 2014, the picture has been complicated by competition between rival governments based in Tripoli and the east and aligned with competing military factions.

Most of Libya’s oil infrastructure is in the east. But even as the LNA grew more powerful, consolidating its position in the east before sweeping into the south earlier this year, oil revenue—which rose about 80% to $24.5 billion in 2018—has continued to flow to the central bank in Tripoli.

The central bank distributes funds including public salaries across the country, but factions in the east say they have received less than their fair share, accusing the Tripoli central bank of favoritism and corruption—charges it denies.

As oil production fluctuated, living standards have fallen steeply. Eastern factions in particular have struggled for funding, printing banknotes in Russia and selling bonds worth more than $23 billion.

The NOC in Tripoli has tried to stay above the political fray. But the eastern government, allied to the LNA, set up a parallel NOC in Benghazi that has repeatedly tried and failed to wrest control over some of Libya’s oil exports.

The Tripoli NOC has also struggled to secure funds to repair ageing infrastructure and suffered from regular power outages amid political turmoil.

Is This Just An Internal Issue?

No. Companies based in countries with key roles in Libya’s conflict either have active stakes in its oil and gas industry or are eyeing future investments.

Italy’s Eni and Total of France have joint ventures with the Tripoli NOC, but their governments have been sharply at odds over Libya policy.

Libya is often seen as a proxy conflict for regional powers, with Haftar’s LNA receiving backing from the United Arab Emirates and Egypt, and to a lesser extent Russia.

Recommended Reading

Going with the Flow: Universities, Operators Team on Flow Assurance Research

2024-03-05 - From Icy Waterfloods to Gas Lift Slugs, operators and researchers at Texas Tech University and the Colorado School of Mines are finding ways to optimize flow assurance, reduce costs and improve wells.

Fracturing’s Geometry Test

2024-02-12 - During SPE’s Hydraulic Fracturing Technical Conference, industry experts looked for answers to their biggest test – fracture geometry.

Haynesville’s Harsh Drilling Conditions Forge Tougher Tech

2024-04-10 - The Haynesville Shale’s high temperatures and tough rock have caused drillers to evolve, advancing technology that benefits the rest of the industry, experts said.

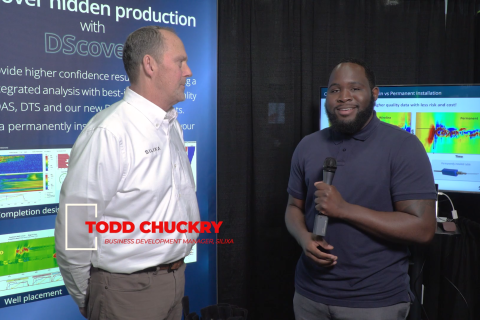

Exclusive: Silixa’s Distributed Fiber Optics Solutions for E&Ps

2024-03-19 - Todd Chuckry, business development manager for Silixa, highlights the company's DScover and Carina platforms to help oil and gas operators fully understand their fiber optics treatments from start to finish in this Hart Energy Exclusive.

2023-2025 Subsea Tieback Round-Up

2024-02-06 - Here's a look at subsea tieback projects across the globe. The first in a two-part series, this report highlights some of the subsea tiebacks scheduled to be online by 2025.