The low-hanging fruit—that is, expanding existing-pipeline capacity — ”has been plucked,” leaving permit reform the only way out for getting U.S. natural gas to markets. And “we’re not giving up,” Chad Zamarin, Williams Cos. executive vice president, corporate strategic development, said at CERAWeek by S&P Global. “We’ve got to get back to building.”

Germany conceived and completed an LNG regasification terminal in under 10 months, he noted, while “we’ve been trying to build Mountain Valley Pipeline [MVP] for eight years.”

“We should be frustrated as a country that we are no longer the leader in building infrastructure,” he said.

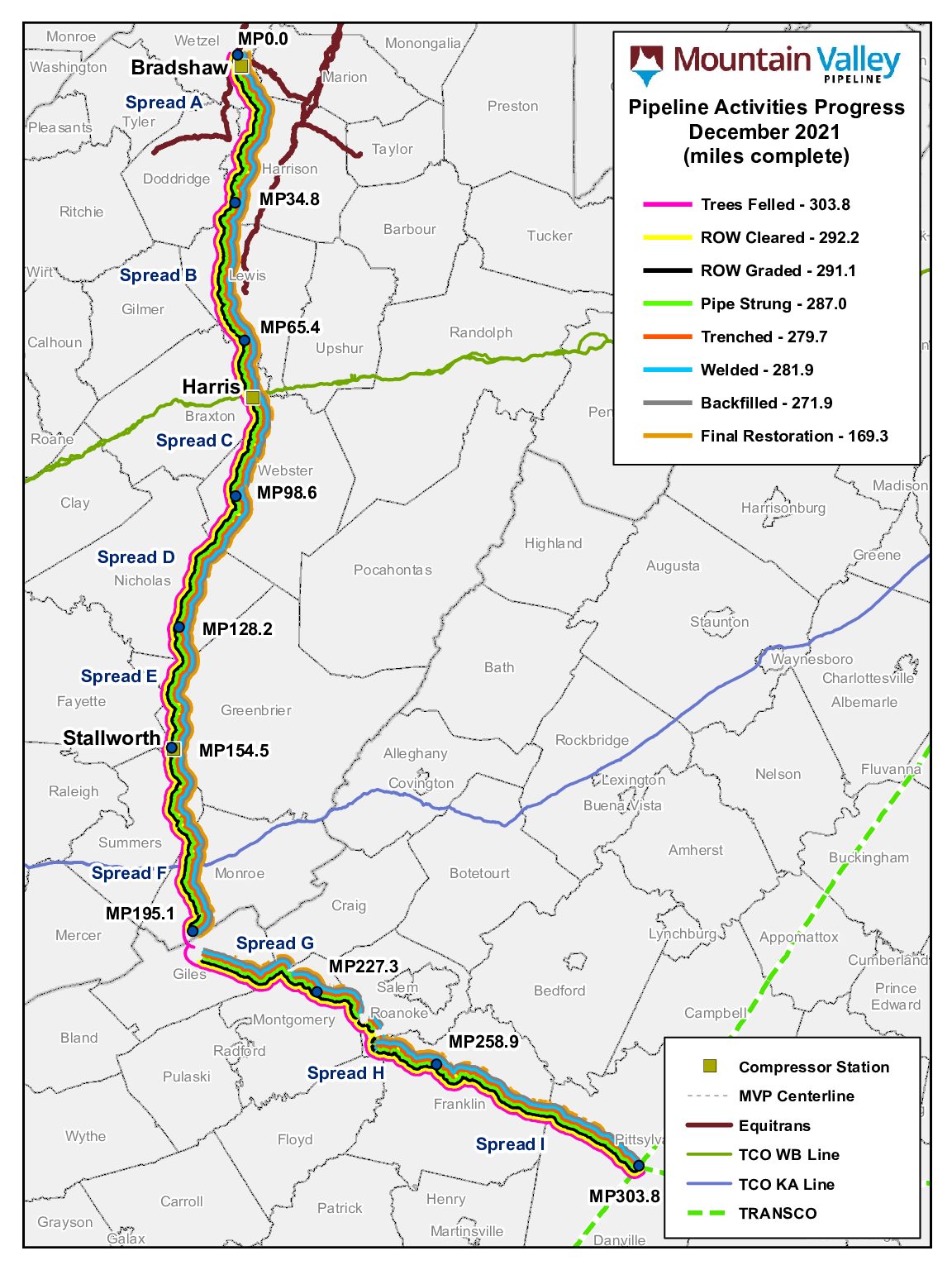

The 42-inch, 303-mile MVP would take Appalachian gas into Virginia, connecting it to consumers along the Atlantic Coast. It’s a joint venture of EQM Midstream Partners LP, Florida Power & Light affiliate NextEra Capital Holdings Inc., Con Edison Transmission Inc., WGL Midstream and RGC Midstream LLC.

The last 20 miles

Only 20 miles remain to be built—the miles that cross the West Virginia-Virginia border. There, the pipe becomes an interstate crossing that needs federal approval.

“We’ve got to be able to unlock Appalachian resources,” Zamarin said. “…The easy stuff has been done. And now, again, we’ve got to get back to building.”

The “easy stuff” is optimization of existing infrastructure. Think of Transco, the largest U.S. gas pipeline, and couch-diving for loose change.

“You can oftentimes find a lot of loose change. It’s a really big couch,” he said.

Individual pipe operators, such as Williams, have found ways of expanding their pipes’ capacity.

“But I do think the industry as a whole needs to take a step back and say, ‘Hey, if we could move gas more efficiently across multiple systems, we can open up pockets of capacity that could unlock, for a much lower cost, capacity … [not just to] the Gulf Coast.

“There are still over 200 coal plants operating in the United States today. We’ve still got work to do to decarbonize the U.S. and we’ve got to build out the capacity to support renewables.”

Yet “we can’t permit a CO2-sequestration well in the United States.”

Currently, “anyone can effectively bring … litigation against one of our projects and it gets you caught in the courts forever. … You shouldn’t be able to [do that] without [meeting] some minimum reasonable threshold standard.”

Building pipelines stall under FERC

Intrastate pipe newbuild has been less complicated because the state has domain. The constraint appears when a pipe needs to cross state lines, falling under federal domain, namely the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC).

Furthering the conundrum, natural gas is a key to the U.S. and its allies reaching decarbonization goals, Zamarin added.

“Natural gas has been the largest decarbonization tool in the United States of the last 15 years. … Over 60% of the emissions reductions that the U.S. has achieved over the last 15 years [is due to] natural gas.”

The U.S.’ annual CO2 emissions have fallen by 5 billion tons upon the advent of reliable and abundant shale-gas production beginning in the aughts.

“So it’s not [just] a ‘theory’ that natural gas is a decarbonization tool,” he said.

Meanwhile, natural gas supply is essential in the growth of renewables in the power grid. “You cannot deploy renewables without having natural gas capacity to backstop the intermittency of renewables.”

Unclogging the permit pipe is essential, too, in getting gas to allies, he added.

“[In the U.S.] we don’t stick the LNG terminal right on top of the resource. We rely on our infrastructure—we [at Williams] pull from 15 different supply basins just across our footprint—to move that gas.”

Other gas exporters, such as Qatar and Australia, have liquefaction infrastructure near the source. Meanwhile, the U.S. “is the only energy system on the planet where you can produce gas far away from where it is consumed.

“I mean, we can produce gas in Wyoming that gets consumed now in Europe,” he said.

And supply is not an issue. “The challenge that we have is infrastructure. It’s getting the resource from where it can be produced responsibly to the demand where it’s needed.”

Besides Europe needing LNG supply for political reasons, “there are still 3 billion people around the world that cook their food and heat their homes with wood, coal or animal manure.

“Those people need access to cleaner, more affordable, reliable energy.”

He has hope, though, as more Democrats appear to be coming onboard with permit pipe-cleaning. “I’m as hopeful as I’ve probably ever been that we can get real permitting reform done,” he concluded.

Recommended Reading

US Drillers Add Oil, Gas Rigs for First Time in Five Weeks

2024-04-19 - The oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, rose by two to 619 in the week to April 19.

Strike Energy Updates 3D Seismic Acquisition in Perth Basin

2024-04-19 - Strike Energy completed its 3D seismic acquisition of Ocean Hill on schedule and under budget, the company said.

Santos’ Pikka Phase 1 in Alaska to Deliver First Oil by 2026

2024-04-18 - Australia's Santos expects first oil to flow from the 80,000 bbl/d Pikka Phase 1 project in Alaska by 2026, diversifying Santos' portfolio and reducing geographic concentration risk.

Iraq to Seek Bids for Oil, Gas Contracts April 27

2024-04-18 - Iraq will auction 30 new oil and gas projects in two licensing rounds distributed across the country.

Vår Energi Hits Oil with Ringhorne North

2024-04-17 - Vår Energi’s North Sea discovery de-risks drilling prospects in the area and could be tied back to Balder area infrastructure.