Gas production from major regions in the U.S. is forecast to grow to more than 80.6 billion cubic feet per day in June, the U.S. Energy Information Administration says. (Source: FerrizFrames/Shutterstock)

HOUSTON—The U.S. shale industry is more mature than some think, according to Gulfport Energy Corp. CEO Dave Wood.

“From the start of the [U.S.] shale revolution to today, there hasn’t really been a new basin found in the last five years,” Wood said. “There are a few new horizons people are playing with in some of the known basins,” but the quality doesn’t match that of basins further along in development or those that have reached maturity.

Plus, the amount of available core acreage is shrinking.

“I think lots of people in our business say ‘Hey, I’ve got the core. I’ve got the core of the core. I’ve got the core of the core of the core, and my core is better than your core,’” Wood told those gathered recently for the AIPN International Petroleum Summit.

But in his opinion if the acreage doesn’t deliver more than 4 billion cubic feet equivalent (Bcfe) per 1,000 ft drilled, then it is not Tier 1. Anything less than the 2 Bcf to 4 Bcf per 1,000 ft range “ain’t worth it in my view,” he said, turning to the Haynesville Shale play for example. Those not in the southern part of Louisiana’s DeSoto and Red River parishes are not Tier 1. “That, to me, is where the drive and returns are going to be made. … What I would suggest to you is we are a lot more mature than we think.”

His words were delivered as production from the seven most prolific oil- and gas-producing regions in the U.S. inches up. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecast June gas production will be more than 80.6 Bcf per day and oil production about 8.5 million barrels per day (MMbbl/d).

Although efficiency in the U.S. oil and gas business has soared in recent years—as operators drill longer laterals, adjust completion recipes for optimal performance and use improved rigs—the boom isn’t expected to last forever.

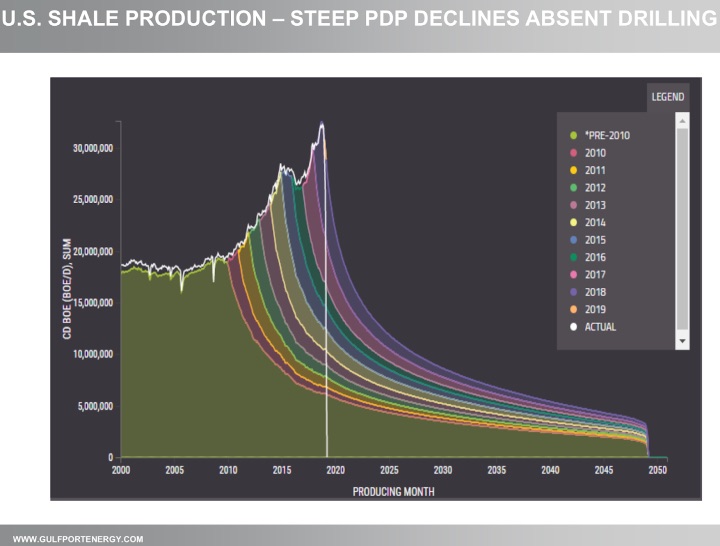

A chart showing the proved developed producing (PDP) evolution of U.S. shale since 2000 and forecast through around 2050 gives industry players something to think about.

“It means we are on a much steeper slope every year continuing forward,” Wood said.

Compared to countries in other parts of the world, the U.S. may have good rock quality, water and skill to get resources out of the ground, the size of the prize is smaller. With about 36.5 billion barrels (Bbbl) of crude oil reserves, the U.S. trails others. EIA data shows Canada has nearly 170 Bbbl of crude oil reserves; Venezuela, more than 300 Bbbl, Saudia Arabia, 266.5 Bbbl; and Russia, 80 Bbbl.

For gas reserves, however, the U.S. ranks fifth, following Iran, Russia, Qatar and Turkmenistan.

“It’s actually not a very large resource,” Wood said of U.S. oil reserves. “We’re probably going to have to deal with a decline in oil production looking forward rather than it continuing to rise. …For gas, the domestic market growth and growing export opportunity underpinned by the fact that here in the U.S. low-cost gas going to higher priced markets is going to be an interesting opportunity set to create significant value as we go forward.”

Following his talk, Wood sat down with Hart Energy for an interview. Wood, whose comments were edited for length and clarity, spoke on what Gulfport—a natural gas E&P with assets in the Utica, Scoop and southern Louisiana—is doing and gave industry insight.

Hart Energy: Regarding PDP, what can the industry do?

Wood: What we [the industry] have to do is spend capital to move reserves that have been discovered but not been developed, so the PUD piece. But it takes capital to move that from PUD to PDP. I think what that curve illustrates is as fast as we’re pedaling that it gets steeper and steeper and harder and harder to keep growth going. In order to do that you’re going to have to keep moving a lot of reserves from that proved undeveloped category into a proved development. And when you have a shortage of capital, like we are starting to get now with private equity starting to dry up a little bit, then I think that’s a bit of a challenge. So that would suggest that that ramp for the last 10 years in production is going to start to turn over because every year you have to work harder and harder.

Hart Energy: What is Gulfport doing?

Wood: We’re focusing in two areas. We’re a natural gas company, so we’re producing gas in Ohio and producing gas in the Midcontinent in Oklahoma in a play called the Scoop. We’re selling out of all the other businesses that we’re in, which are relatively small, redeploying that capital and making a returns-focused business rather than a growth business. So, for our shareholders we’re looking to generate free cash flow, and we’re looking right now to buy back stock to return back to our shareholders. We are not a real growth in production business anymore. I just joined the company in December of last year, and we changed from being a growth company to being a returns company because I thought that was the best place for us to generate returns for our shareholders.

Hart Energy: So are you more focused on oil now?

Wood: No, we produce very little. We produce about 1.35 Bcf a day and we produce about 7,000 barrels of liquids. So very, very small liquids. They have high economic value. They’re all in Oklahoma, and so the capital that we’re spending this year and into next year will become more focused on that because that oil kind of drives some of the economic returns.

Hart Energy: Can you tell me a little bit more about these super long laterals that are being drilled in the Utica? How economic are those?

Wood: The game really is relatively simple. It costs the same to drill down to the target horizon and when you get in the particular reservoir the efficiency gets better and better the longer the lateral you drill. … The more thousand feet I can put together means the capital I spent to get down into the reservoir is much more efficient. [But] a lot of it depends on the quality of the rock. We’re fortunate like other people in Ohio that you can drill very long laterals. We last year drilled a well that was a little over 16,000 ft, so that becomes a very efficient well in terms of the capital we spend.

Hart Energy: Is that starting to become the norm?

Wood: For us, up in Ohio, I doubt if we’ll drill any wells less than 11,000 ft. If we can push them to average north of 12,000 ft I think that’ll be our new norm.

Hart Energy: Does going that long pose any challenges?

Wood: Yeah. There are a whole bunch of mechanical challenges. When you have a wellbore that is horizontal—and they’re not exactly flat; they may be slightly up or slightly down—how you clean the rock chippings out of that wellbore, the mud rheology and the efficiency of cleaning becomes a critical factor. If you don’t clean it, you’ll just keep re-drilling the same piece of rock. Then you won’t get the penetration rates that you need. But mud technology, drillbit technology, knowledge of the rock is getting better and better and better every year. So we feel comfortable, I think other people are comfortable, you can drill those long lateral lengths.

Hart Energy: So are you guys still looking to simplify your portfolio?

Wood: We have small interests in Louisiana. We have an interest in a public service company called Mammoth. We have an interest in an oil sands company that’s not producing right now. We have a few other small things. So all of those are things we’ll end up selling probably this year and maybe a little bit into next year. Then we’ll just be down to the Scoop in Oklahoma and the Ohio production in the Utica.

Hart Energy: And you’re also divesting your Scoop water infrastructure. How is that going?

Wood: If you look at a business like ours say OK we’re valued in the market at about three and a half times of our EBITDA. That business in the marketplace should be many times more valuable than that. So the question to me is it’s not valued in my stock. I can get terms on it that bring cash to me, and it doesn’t impact negatively my business. So why not monetize it? We have an advisor. We have a data room stood up and so that process is kicking off.

Hart Energy: Can I get your thoughts on today’s M&A climate in general?

Wood: If I look at each of the basins—not just the ones we’re in—there’s a lot more players than there should be because a lot of them were picked up with the idea that they would buy the acreage, do something to it and sell it to someone. Now in this flat price environment you actually have to start generating returns. One way you can do that most efficiently is build scale. Let’s look at Appalachia. You may go from 30 players down to five or six players in the next round of M&A. I think that’s probably something that could kick off with a little bit better gas price than we’ve got now. To do a deal you have to have both sides say that it’s possible. I don’t see it as a bad thing. I think it’s a good thing.

Velda Addison can be reached at vaddison@hartenergy.com.

Recommended Reading

Shell’s CEO Sawan Says Confidence in US LNG is Slipping

2024-02-05 - Issues related to Venture Global LNG’s contract commitments and U.S. President Joe Biden’s recent decision to pause approvals of new U.S. liquefaction plants have raised questions about the reliability of the American LNG sector, according to Shell CEO Wael Sawan.

BP Pursues ‘25-by-‘25’ Target to Amp Up LNG Production

2024-02-15 - BP wants to boost its LNG portfolio to 25 mtpa by 2025 under a plan dubbed “25-by-25,” upping its portfolio by 9% compared to 2023, CEO Murray Auchincloss said during the company’s webcast with analysts.

Mitsubishi Makes Investment in MidOcean Energy LNG

2024-04-02 - MidOcean said Mitsubishi’s investment will help push a competitive long-term LNG growth platform for the company.

Mexico Pacific Appoints New CEO Bairstow

2024-04-15 - Sarah Bairstow joined Mexico Pacific Ltd. in 2019 and is assuming the CEO role following Ivan Van der Walt’s resignation.

Nebula Energy Buys Majority Stake in AG&P LNG

2024-01-31 - AG&P will now operate as an independent subsidiary of Nebula Energy with key offices in UAE, Singapore, India, Vietnam and Indonesia.