(Source: FreezeFrames/Shutterstock.com)

As U.S. shale oil activity recovers, still coping with the coronavirus-driven demand slowdown, a new business model has emerged and companies are reinvesting less than previous years, according to analysis from Rystad Energy.

How tight oil businesses are run began to change dramatically last year but the latest downturn hastened the shift. Amid investor demand for more sustainable energy development, capital discipline, efficiency gains and free cash flow generation have become the norm. Many are also putting less back into the shale business compared to previous years as others merge, setting the stage for moderated growth.

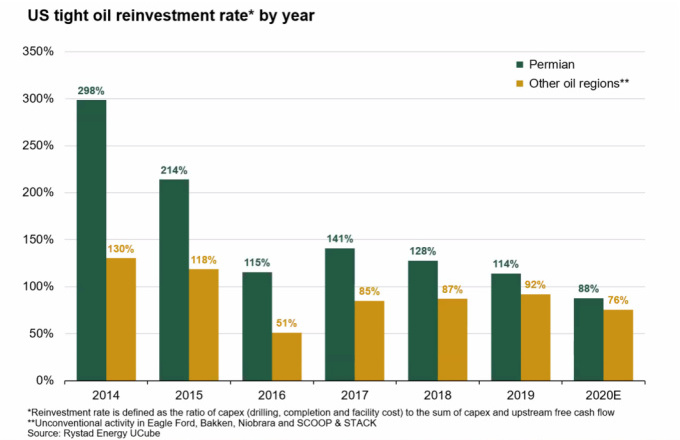

Historically, the tight oil industry has reinvested more than 100% of its operational cash flow back into drilling and completion costs, said Artem Abramov, partner and head of shale research for Rystad Energy.

“The COVID-19 pandemic sort of accelerated the transformation of the industry—a move toward this new business model,” Abramov said during a recent webinar with Haynes and Boone. “In fact, 2020 is the first year in the modern history of the Permian when a reinvestment rate is below 100%. It is on track to be at 85 to 90%.”

Rystad Energy data show the U.S. tight oil reinvestment rate—defined as the ratio of drilling, completion and facility cost, or capex, to the sum of capex and upstream cash flow—was 298% for the Permian Basin in 2014. That was down to 114% by 2019.

The rate for other oil regions, including the Eagle Ford, Bakken, Niobrara and SCOOP/STACK, grew from 130% in 2014 to 214% in 2015 before dropping to 115% the following year. The rate is now estimated to be 76% this year, according to Rystad.

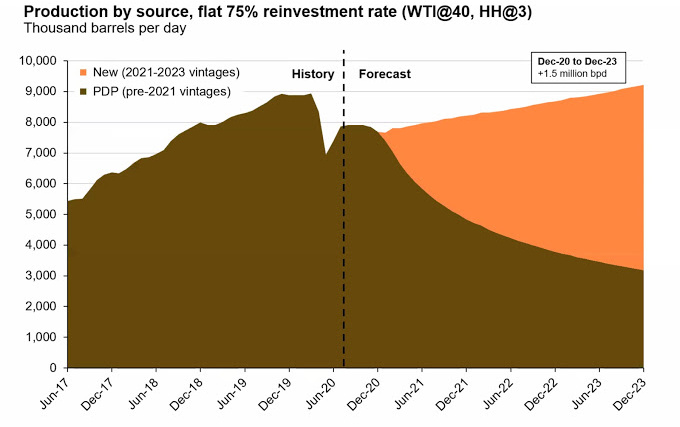

“If you freeze the reinvestment rate at the current level of 75% and use the current strip pricing, the base decline and the current type curves, then the key message is that the tight oil production can start growing again at some point in late 2021,” Abramov said, later noting the feasibility of the percentage is debatable. “We won’t be talking about dramatic production expansion at the base, which we saw in 2018-2019, but we still might return to pre-COVID production records.”

Source: Rystad Energy ShaleWellCube, Rystad Energy research and analysis

Just about all of the growth is expected to come from the Permian Basin, the biggest oil-producing region in the U.S.

“Outside of the Permian, we’ll only have some core areas of Bakken, Eagle Ford, D-J (Denver-Julesburg) Basin that will be able to recover,” Abramov added. “But this recovery will likely be offset by declines elsewhere.”

Consolidation Wave

The views were shared as the industry sees a pickup in M&A activity, following a slow start to dealmaking earlier this year. Notable deals include Chevron Corp.’s $13 billion takeover of Noble Energy along with the pending union of shale producers Devon Energy Corp. and WPX Energy Inc. The latest came this week with ConocoPhillips’ agreement to acquire Permian pure-play Concho Resources Inc. followed by the merger of Pioneer Natural Resources Co. and Parsley Energy Inc., both also Permian pure-plays.

Companies with strong balance sheets are combining their efforts, Abramov said, driven mainly by the attractiveness of the Permian Basin.

The consolidation wave could lead to a slowdown in growth rates and capital spending, he said, noting most targets in these deals were earlier on the growth cycle and aimed to move the buyer to new levels of size and maturity.

“Many large producers [are] now talking about long-term reinvestment rate targets of 60%,” Abramov continued. “And if we just assume for a second that the whole industry starts from 75% reinvestment rates and gradually move toward 60% by 2023, then the growth story for the U.S. tight oil is actually over completely.”

In this scenario, only the Permian Basin would return to pre-COVID production records, he said. Though he called the scenario extreme, it paints of picture of the lowest production case under today’s price environment.

“Back to the main implication from consolidation is that we’ll see fewer E&P names in the next few years, but these companies will be much larger and they’re in a much stronger financial shape,” Abramov added. Such companies are not expected to need too much external capital with moderated growth rate ambitions of about 3% to 5%.

Recommended Reading

US Raises Crude Production Growth Forecast for 2024

2024-03-12 - U.S. crude oil production will rise by 260,000 bbl/d to 13.19 MMbbl/d this year, the EIA said in its Short-Term Energy Outlook.

To Dawson: EOG, SM Energy, More Aim to Push Midland Heat Map North

2024-02-22 - SM Energy joined Birch Operations, EOG Resources and Callon Petroleum in applying the newest D&C intel to areas north of Midland and Martin counties.

Tethys Oil Releases March Production Results

2024-04-17 - Tethys Oil said the official selling price of its Oman Export Blend oil was $78.75/bbl.

CEO: Continental Adds Midland Basin Acreage, Explores Woodford, Barnett

2024-04-11 - Continental Resources is adding leases in Midland and Ector counties, Texas, as the private E&P hunts for drilling locations to explore. Continental is also testing deeper Barnett and Woodford intervals across its Permian footprint, CEO Doug Lawler said in an exclusive interview.

Range Resources Expecting Production Increase in 4Q Production Results

2024-02-08 - Range Resources reports settlement gains from 2020 North Louisiana asset sale.