Learn more about Hart Energy Conferences

Get our latest conference schedules, updates and insights straight to your inbox.

[Editor's note: This story originally appeared in the April 2020 edition of E&P. Subscribe to the magazine here. This story was developed and went to press as the COVID-19 crisis grew exponentially in the U.S. and globally. Taken together with a sudden global oil supply glut, financial markets and the industry have been severely affected. While many producers have cut back their spending plans or are delaying work, impact on deepwater projects is still unknown. Check HartEnergy.com for updates on Gulf of Mexico activity that occurred after this story went to press.]

If the U.S. Gulf of Mexico (GoM) oil and gas industry were a cat, then it would easily be on its 12th or 13th life by now. In its more than eight decades of existence, the industry has weathered considerable highs and lows. Its advances on multiple fronts in that period have been hard-earned and beyond impressive.

From the spudding of the first offshore well in the Creole Field in 1938 about a mile from the shores of Louisiana’s Cameron Parish to the modern-day greenlighting of the region’s first ultrahigh-pressure development of the Anchor Field about 140 miles off the same coast, the industry’s ingenuity and innovation have kept the GoM’s fields producing even in the lean years.

“The Gulf of Mexico represents a very large resource play for Chevron. We see deep water as a very successful and competitive business opportunity,” said Mark Hatfield, vice president of Chevron’s GoM business unit. “Recent breakthroughs in technology have opened up new opportunities, like the high-pressure, high-temperature reservoirs in the Wilcox and the Norphlet. Our deepwater assets at Jack St. Malo, Big Foot and Tahiti have the scale and provide a lot of incremental drilling opportunities to extend those production platforms and deliver strong returns.”

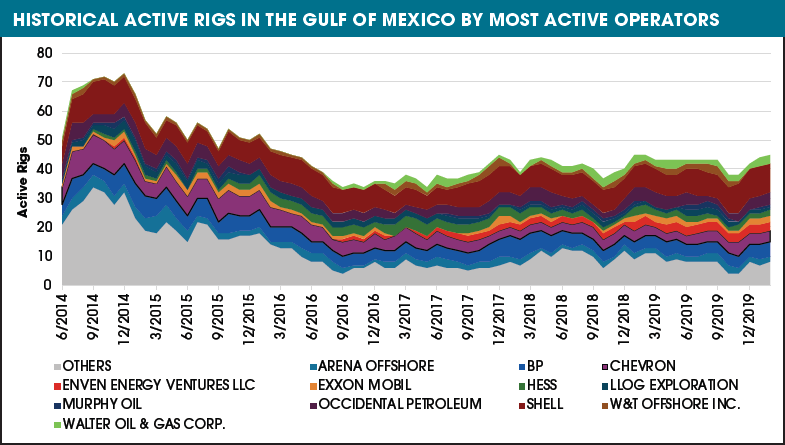

While the collapse in oil prices in 2014 forced hard decisions, it was not all negative.

“The positive side of the downturn is that it brought the offshore industry together to find ways to become more efficient at the individual company level and as an industry as a whole,” said Erik Milito, president of the National Ocean Industries Association. “It enabled the oil and gas industry to find ways to turn a profit in an era of low cost, low price oil and ensure the industry will continue to thrive for a long time.”

Another positive is less obvious but significant.

“We see overall the number of companies in the Gulf of Mexico has shrunk dramatically from more than 100 down to fewer than 50 now, but it is good because it creates diversity,” he said. “The companies in the Gulf of Mexico now create diversity in the types of projects that are being pursued. So we have new companies moving in, looking at shallow water, deep water or ultradeep water, and pursuing projects. The Gulf of Mexico is a good investment overall.”

M&A activity over the past two years saw the shifting of assets between existing GoM E&P companies, the return of former players and the entrance of new players. Combined with greenfield projects, record production levels and advances in offshore technologies, it is easy to believe that the GoM is back once more. E&P recently sat down with a cross section of some of the leading players to get their views on the steadily resurging GoM.

Breaking records, pushing forward

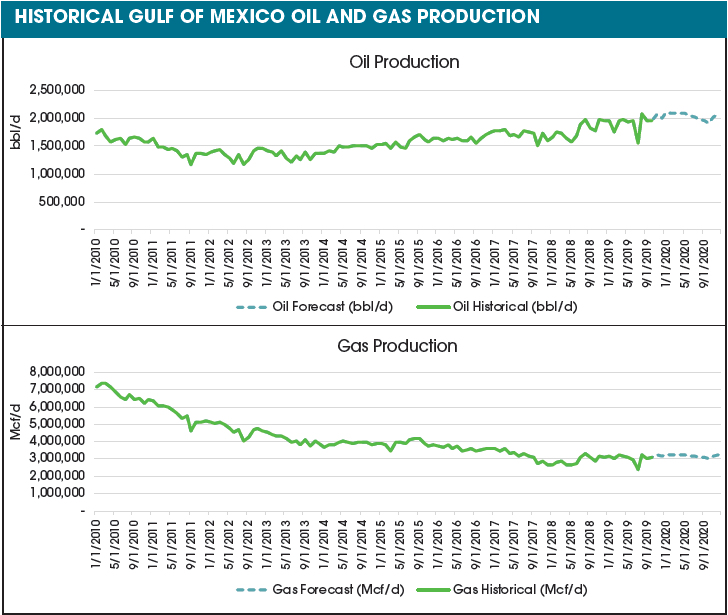

As the industry turned the page on a new decade, it did so with two years of record-breaking production under its belt and with E&P companies ready for another year of record growth.

In 2018 GoM crude oil production was about 1.8 MMbbl/d, setting a new annual record, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). It did it again in 2019 when production hit 1.9 MMbbl/d, and that’s after accounting for hurricane-related shut-ins. The EIA’s latest Short-Term Energy Outlook forecasts annual crude oil production in the GoM will increase to an average of 2 MMbbl/d in 2020.

The GoM deep water will provide most of 2020’s growth, according to a Rystad Energy release. Oil production in the GoM has grown every year since 2013, with an average of 104,000 bbl/d of oil added annually, with infill drilling in legacy producing fields such as Mars and Thunder Horse providing an essential contribution. With its startup in May 2019, the Appomattox Field will make a significant production contribution as it ramped up toward its processing capacity of 175,000 boe/d, according to the release.

Deepwater discoveries in the GoM will lead offshore production to reach a record 2.4 MMbbl/d in 2026, according to the EIA’s 2020 Annual Energy Outlook.

The increases in production and activity are generating positive vibes across the sector.

“Overall, we are optimistic with regard to the level of activity in the Gulf,” said Thierry Conti, senior vice president of subsea product management for TechnipFMC. “The overall activity should continue to grow in 2020, and we anticipate a 10% to 20% increase in terms of spending in 2020 versus 2019, based on business opportunities and awards in our pipeline. It is too early to assess how the recent uncertainties in the market will affect demand and how oil prices will impact this picture.”

The versatility of the GoM also contributes to its success in that it offers multiple development options to ensure competitiveness.

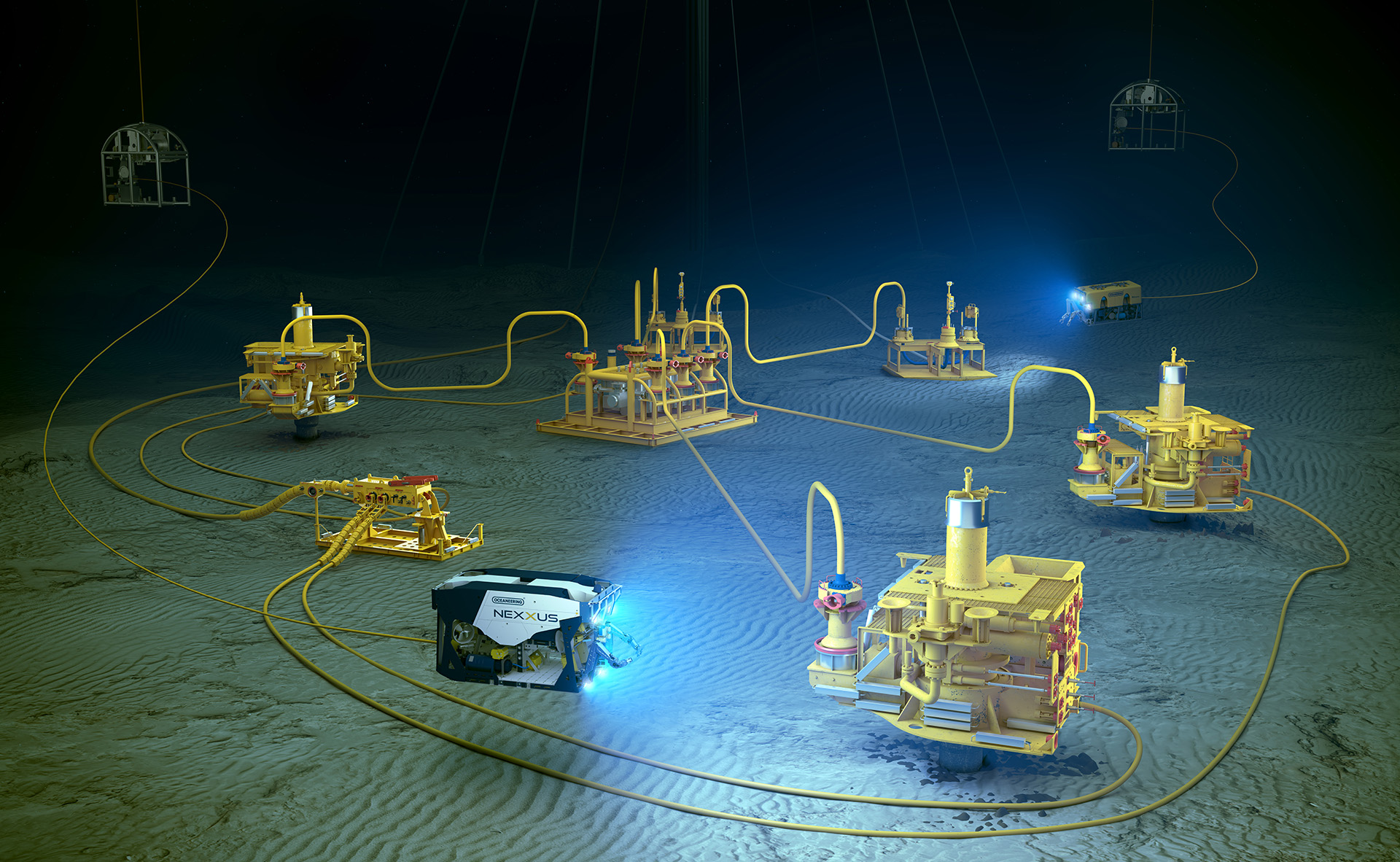

“The Gulf is a key part of the global picture,” said Don Sweet, president of OneSubsea, Schlumberger. “I think of the Gulf as two markets. It is a robust subsea tieback market, one where our customers want to leverage their existing infrastructure, keep the host full, and in many cases, they want to do that quickly.” The GoM’s other market is greenfield, requiring a “different type of delivery schedule because it is dictated by a new host,” he said.

The pairing of legacy fields and their low rates of decline with fresh production from new field development projects has provided the GoM with an advantage over other investment options.

“The Gulf of Mexico benefits from having well-developed infrastructure with opportunities to add additional barrels of oil without needing more infrastructure to do it,” said Steve Barrett, senior vice president of business development for Oceaneering. “The market has played out pretty positively in terms of benefiting from the huge greenfield developments that occurred from 2005 to 2015. That 10-year span positioned the Gulf of Mexico in a good way to take advantage of tiebacks and cost-effective ways to exploit reserves that are still undeveloped.”

According to Matt McCarroll, president and CEO of Fieldwood Energy, the widespread use of subsea tiebacks is due to improvements in reliability, safety and more.

“Subsea tiebacks have been around forever. People tend to focus on the big projects with new infrastructure, but there are subsea tiebacks to Bullwinkle that have been out there for 20 years,” he said. “The technology has improved, and the reliability and safety of the equipment are better. What has made tiebacks a more attractive option are the subsea trees, wellheads, controls and umbilicals are more or less standardized.”

For an independent operator like Fieldwood, standardization is helping the company keep costs low and get to first oil faster.

“We do not need to start from scratch and build ‘serial No. 1’ every time we build something,” McCarroll said. “Let’s find something that has multiple uses and fits; you can mix and match it. It’ll be cheaper and we’ll understand it better. When we can drill, complete and tieback for $125 million or $135 million, those wells become cheaper, and it enables us to have smaller reserve targets and much lower breakeven costs when your total project costs have come down that far.”

Activity bright spots

There is plenty of activity bubbling away in the GoM. For example, LLOG Exploration announced in June 2019 that the initial phase of the Buckskin Project was online with production from two wells flowing through a 6-mile tieback to the Lucius Platform.

The company noted that the drilling, completion and subsea installation were completed ahead of schedule and on budget. Anticipated Phase 1 production is 30,000 bbl/d, with additional phases required to fully develop the field’s estimated 5 Bbbl of original oil in place.

Talos Energy deepened its U.S. GoM portfolio in December with a series of deals with three private-equity-backed companies worth $640 million, acquiring assets that include more than 40 identified exploration prospects located on total footprint of about 700,000 gross acres. The acquired assets produced 19,000 boe/d, consisting of 65% oil and more than 70% liquids during the third quarter last year, increasing the company’s production to 72,000 boe/d.

“This transaction allows Talos to increase its 2019 production and 2P reserves by 35% and become one of the top 10 producers in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico (including both shelf and deep water),” said Mfon Usoro, from Wood Mackenzie’s GoM upstream team, in a release. “The assets acquired have some of the most competitive economics, and Wood Mackenzie estimates the point-forward breakeven for the majority of the assets at less than $15/bbl.”

Drilling activity in the basin is brisk, too, as more than one contractor has noted in their quarterly reports.

Seadrill announced in February 2020 that Walter Oil & Gas Corp. extended its contract for the Sevan Louisiana to June 2020 with a day rate of $145,000. The drilling contractor also announced that LLOG Exploration contracted its seventh-generation drillship, West Neptune, with a day rate of $202,000 to the end of the year for its GoM operations.

Transocean’s president and CEO, Jeremy Thigpen, noted in his fourth-quarter 2019 remarks that the market for high-specification assets is “virtually sold out for the majority of 2020,” adding that the company is receiving inquiries about bringing additional rigs into the GoM to meet demand.

“As our customers continue to realize the favorable economics offshore, we are witnessing a shift in focus toward the deep water. The opportunities include greenfield development, tiebacks and exploration,” he said. “Some industry reports indicate that deepwater exploration projects will outpace development in 2020 for the first time since 2014.”

Thigpen also noted that Talos Energy signed a four-month contract for its sixth-generation drillship, the Deepwater Inspiration, at a day rate of $210,000.

Contributing to the success of deepwater are improvements in technologies that have made it possible to locate and tie back nearby resources to existing production platforms.

Anchors away on 20k

In late February, Chevron took another step closer to dropping anchor at its Anchor Field with the news that Wood is heading up the multimillion-dollar design project for the supermajor’s deepwater development.

It was a quiet but significant step for the $5.7 billion project sanctioned in late December 2019 by Chevron. It is a project that Wood has been involved in since 2017 with its work on the preliminary FEED (pre-FEED) and FEED.

The project now focuses on the design of the wet tree development that will use a semisubmersible floating production unit (FPU) and will have a production capacity of 75,000 bbl/d of oil and 28 MMcf/d of gas, with room for future expansion, according to a press release.

“The delivery of new technology capable of handling pressures of 20,000 psi also enabled access to other high-pressure resource opportunities across the Gulf to Chevron and the industry. Ultimately, our investment decisions fundamentally come down to the economics that we anticipate out of an individual development,” Hatfield said.

“And those are obviously influenced by the size of the resource, the development strategy, whether it’s a tieback or a newbuild and the complexity of the reservoir,” he said. “It’s really all about making choices and doing what we believe will be the best opportunity to secure good returns for our portfolio.”

One particular enabling technology need for the development of 20k fields is the drillship. For the Anchor Field, this will be Transocean’s seventh-generation drillship Deepwater Titan. It will be the first ultradeepwater floater rated for 20k-psi operations, which are expected to commence in the second half of 2021 at the Anchor Field. The drillship will feature dual 20k-psi BOP, a hookload capacity of 3 MMlb and a 165-ton active heave compensating crane.

“Construction on the Deepwater Titan has progressed as planned, and we look forward to delivering this drillship to Chevron for her maiden contract commencing in 2021,” Thigpen said in his fourth-quarter 2019 remarks. “This five-year contract will allow Chevron to construct and ultimately produce the first fields in this extremely high-pressure area of the Lower Tertiary in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico. The desire to exploit this basin is driven by the exceptional returns Chevron anticipates, with development costs for this first field, Anchor, now estimated to be as low as $20 per barrel.”

Chevron is the operator of the Anchor discovery with a 62.86% interest and Total is its partner with a working interest of 37.14%, according to a release. The project is one of three 20k-psi developments underway in the deepwater GoM. In October 2019, LLOG Exploration ordered the first 20k-psi-rated subsea trees from TechnipFMC for its Shenandoah Field located about 200 miles south of New Orleans.

The third is at the North Platte Field, discovered in 2012 by Total and Cobalt International, and located about 170 miles south of Houma, La. The field development plan is based on eight subsea wells and two subsea drilling bases connected via two production loops to a newbuild, lightweight FPU.

Worley announced in January 2020 that it was awarded the FEED contract for the field development and the semi-FPU moored in water more than 1,300 m deep, with a production capacity of 75,000 bbl/d. Total operates North Platte with a 60% working interest, alongside Equinor (40%), according to the Form 6-K that the company filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Total is expected to make its final investment decision in 2021.

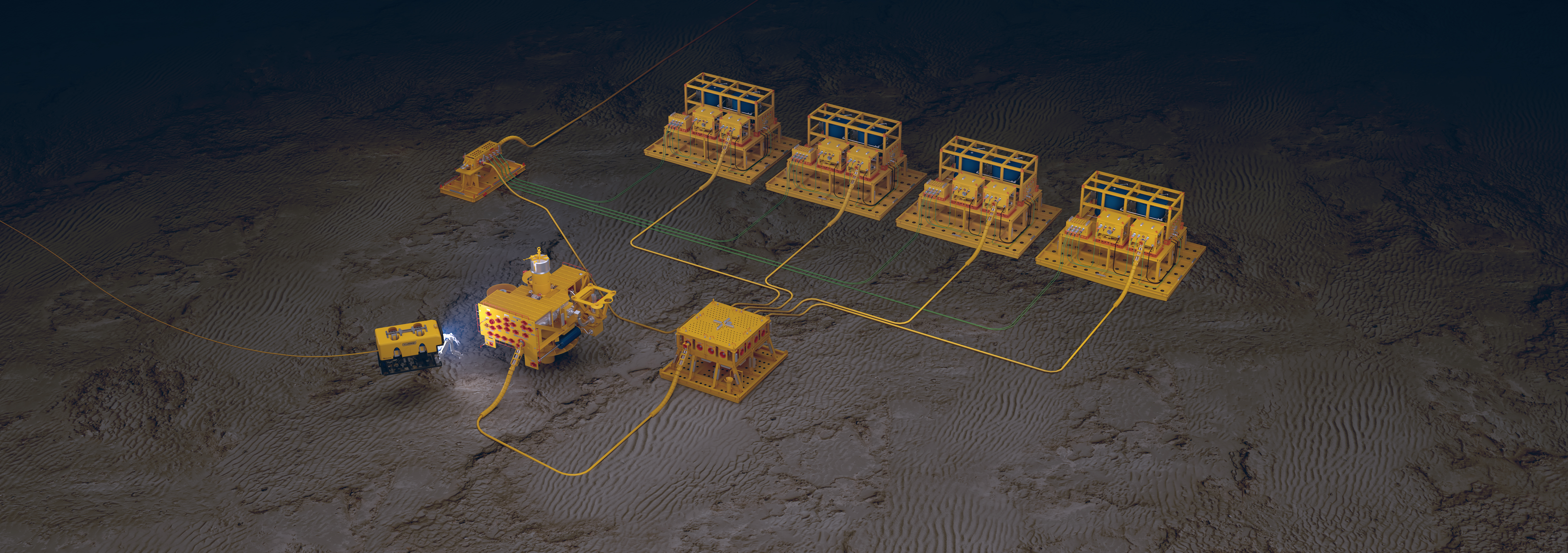

Subsea execution

Signs are pointing to a positive year ahead for many in the subsea sector. According to TechnipFMC’s Conti, the adoption of its fully integrated solutions and execution model or iEPCI “continues to gain traction by its clients.

“In 2020 we are executing five iEPCI projects in the Gulf of Mexico,” he said. “In addition, we are seeing increasing demand for subsea trees and flexible jumpers and increases in customer support operations in terms of equipment refurbishments and interventions.”

He added that the company helps its clients maintain low-breakeven developments and improve project economics through early engagement, noting that the early collaboration with clients and the supply chain is “essential in really impacting the value drivers.”

“We also drive standards and configurability in our products, fix what can be easily get fixed and accept to keep variables to a minimum,” he said. “Our Subsea 2.0 platform is a perfect example in that it is a fully pre-engineered set of configurations for certain types of equipment, a kind of catalog of fit, form and functions. By achieving this and because we are vertically integrated from SPS to SURF [subsea production systems to subsea umbilicals, risers and flowlines], we can then line up our delivery model with those standard configurations to drive costs down by taking out the excess variability.”

Baker Hughes’ Raymond Semple, vice president of subsea production systems and services, said he expects to see “smaller projects to continue dominating awards, with many initiated in 2019 and on a fast track for first oil in the first quarter of 2021 through the first quarter of 2022."

He added, "Our GoM clients need robust and repeatable execution plans that reliably and predictably reduce the time and schedule to first production with minimal interface risk. Additionally, they require the same level of certainty throughout the production phase. Our industry recognizes that the potential for any deviation to the project budget or schedule must be eliminated or mitigated at the earliest possible stage in order to provide execution certainty. This is especially the case for short-cycle tieback developments."

One way Baker Hughes is accomplishing this is through the use of its Subsea Connect strategy, Semple said.

“Through this strategy, we are engaging clients at stages either just before or during drilling and offering reservoir, well construction, subsea and well intervention engineering services to cover the concept selection, pre-FEED and FEED phases of the project, which play to our strengths and provide execution certainty not only at the initial development stage but throughout life of field," he said. "When beneficial to our customers, we pragmatically partner in the SURF space to provide a comprehensive subsea EPCI [engineering, procurement, construction and installation] offering, which spans reservoir to topsides plus life-of-field well intervention."

The GoM, according to Oceaneering’s Barrett, “has been a more stable, tieback-driven environment, and our clients are now more confident because they have seen much success in extending the life of their assets.”

Shorter cycle times are one sure way to improve returns, according to Chevron’s Hatfield.

“If we have fairly high confidence in a project, we’ll order the items that have longer lead times, like subsea equipment and some wellhead equipment, that might take a bit longer,” he said. “What we also do, though, is try to reduce the cycle times, which can largely be accomplished through standardization. It is a real big focus for Chevron and the rest of the industry quite honestly. The more we can standardize our equipment, then that benefits not only an individual company, but it also benefits the contractor as well.”

According to Sweet, short cycle times are key to being competitive in tight capital conditions.

“When you’re competing with other capital inside of an operator like unconventionals, then we want the Gulf to be competitive. It is important to help drive costs out through the selection of standard equipment and short delivery times,” he said.

The push for standardization across the industry is one that Barrett believes is growing.

“Operators are really committed to equipment and process standardization to continue to drive cost efficiencies,” he said. “They want to be able to execute small drill centers with four to six wells and single well tiebacks to get to first oil very quickly, which is the most significant factor that is positively impacting the returns on these projects.

“Lead times are important and critical to our customers, and some lead times have increased, particularly in the umbilical business. To shorten these lead times, we are engaging much earlier with clients and still need to employ much higher levels of standardization,” he continued. “There are opportunities to work with customers toward more stocking or pre-ordering. Higher degrees of collaboration with demand planning will really help us deliver more customer success with shorter lead times.”

Go far or stay close?

Pushing out the distance of subsea tiebacks is also underway, according to Hatfield.

“We’ve been working on technology to extend subsea tiebacks for quite some time. It includes the long-distance pumping of fluids and the ability to avoid formation hydrates on the seafloor,” he said. “Pushing that range from the neighborhood of maybe 30 miles out to 50 miles or greater really expands the opportunities for us to use our existing infrastructure. We’re working on multiphase pumps and a number of these technologies right now.”

Multiphase boosting is key to achieving full asset potential. The greater pressure drawdown enabled by multiphase boosting ensures operators achieve higher production rates and greater oil and gas recovery.

Flow assurance is one particular challenge with long-distance tiebacks addressed through a variety of technologies, including flowline heating and multiphase subsea pumps, which comes down to physics, according to OneSubsea’s Sweet.

“Multiphase boosting accelerates recovery and improves flow rates to help operators achieve higher production earlier in the project cycle, which leads to a decreased payback time,” he said. “Additionally, boosting helps with flow assurance challenges by mitigating slugging flow and increase in the fluid’s temperature that comes from boosting the fluid.”

On some long-distance tiebacks, flowline heating requirements can be reduced or eliminated while the multiphase pump system is in operation, he added.

In December 2019, OneSubsea announced it had been awarded a contract by Chevron to supply an integrated subsea production and multiphase boosting system for the Anchor Field.

OneSubsea will supply vertical monobore production trees and multiphase flowmeters rated up to 20,000 psi, according to the company. Also included are production manifolds and an integrated manifold multiphase pump station rated to 16,500 psi, subsea controls and distribution. It is the first 20,000-psi subsea production system contract in the industry.

The equipment that will be deployed in this project is covered under the 20-year subsea equipment and services master order for Chevron’s development projects in the GoM. Projects will benefit from a preapproved catalog of standard subsea equipment, enabling Chevron to reduce investment costs while improving its subsea development performance.

According to TechnipFMC’s Conti, the most exciting and challenging methods of improving production are subsea multiphase boosting and water injection.

“The use of subsea multiphase pumps can increase production by 30% to 50% on average when compared to initial baseline and well-type curve, which ultimately drives a better recovery factor,” Conti said.

“A secondary benefit is that boosting improves flow assurance and protects the tail-end production of the fields. Soon, distributed subsea boosting could be enabled by more cost-effective pumping solutions, subsea power distribution and subsea hardware integration. This could open more boosting opportunities and more economical EOR opportunities for our clients,” Conti said.

For water injection, it is the lack of real estate on existing platforms that poses a significant challenge.

“The treatment and injection of water requires considerable power and space,” he said. “Corrosion management of the subsea lines is another challenge. We are working on multiple technologies now to enhance this lift option, including the development of a subsea seawater treatment and injection system and the use of plastic line pipe.”

Taking the treatment and injection process subsea solves the topsides real estate problem and simplifies it, reduces the number of personnel on board and eliminates emissions, he added.

“By simplifying the topsides, you remedy some of those challenges,” Conti said.

Subsea factories provide a way to improve production at the wellhead. Oceaneering enables this option with its Subsea Pumping Technology (SPT).

“We believe it is a key to enabling subsea factories,” said Todd Newell, vice president of technology for the company. “SPT takes electric pumps, fluid storage and associated controls and places them into dedicated modules, moving them closer to production infrastructure subsea.”

By placing the chemical source and rotating equipment closer to the well, faster response times for chemical delivery compared to a standard umbilical are enabled, he noted.

“Not only can operators save time, but they can reduce the capital expenditure costs associated with long stepouts (lengths greater than 31 miles) by 50% versus traditional methods because the umbilical will be far less complex, requiring only power and communications,” he said.

SPT is scalable, with the fluid storage modules able to be set up with a pair of 1,500-gal. bladders in the ISO container-dimensioned frame, he added.

“It makes the system road-transportable, and two frames can be connected to provide up to 6,000 gallons of fluids for the well,” he said. “The bladders can either be refilled in place, or empty modules can be retrieved and replaced. The technology is at a readiness level of 5 on the API17N scale, and we are exploring customer partnerships to advance it further.”

Advancing technologies through collaborative partnerships in all forms have helped extend the life of the GoM. So has knowing when to adjust the sails when the market waters get choppy. And if there’s any truth to the superstition that cats onboard a vessel bring good luck, then the GoM’s oil and gas industry has a few more lives left in it.

“The Gulf got a bad name for a long time, and then people had been saying the Gulf of Mexico’s dead for 20 years. We started our first Gulf of Mexico company in 2008 and our business plan was to get in because everyone else was getting out,” McCarroll said. “It’s always been a buyer’s market.”

Recommended Reading

Exxon Mobil Guyana Awards Two Contracts for its Whiptail Project

2024-04-16 - Exxon Mobil Guyana awarded Strohm and TechnipFMC with contracts for its Whiptail Project located offshore in Guyana’s Stabroek Block.

Deepwater Roundup 2024: Offshore Europe, Middle East

2024-04-16 - Part three of Hart Energy’s 2024 Deepwater Roundup takes a look at Europe and the Middle East. Aphrodite, Cyprus’ first offshore project looks to come online in 2027 and Phase 2 of TPAO-operated Sakarya Field looks to come onstream the following year.

E&P Highlights: April 15, 2024

2024-04-15 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including an ultra-deepwater discovery and new contract awards.

Trio Petroleum to Increase Monterey County Oil Production

2024-04-15 - Trio Petroleum’s HH-1 well in McCool Ranch and the HV-3A well in the Presidents Field collectively produce about 75 bbl/d.

Trillion Energy Begins SASB Revitalization Project

2024-04-15 - Trillion Energy reported 49 m of new gas pay will be perforated in four wells.