Regulatory hurdles that have led to cancellation or delays for natural gas pipelines, like the Mountain Valley Pipeline, have resulted in a shift of capital from Appalachia to the Gulf Coast. (Source: Hart Energy photo illustration; Malachi Jacobs, grebeshkovmaxim/Shutterstock.com)

HOUSTON—Infrastructure constraints in the Marcellus and Utica shale plays are not just keeping the natural gas in, they are keeping capital out, Kevin Little, senior vice president for natural gas at Macquarie Energy, said at Hart Energy’s recent America’s Natural Gas conference.

“The regulatory burdens are creating a dislocation in the markets,” Little said. “Whereas, the Marcellus and Utica led in the terms of growth through 2019, now, we’re expecting this to shift down to Texas-Louisiana—specifically, in the immediate term, Haynesville.

“You’re just seeing a shift in capital away from Marcellus and Utica down to the Gulf Coast.”

Good for the Gulf Coast in terms of its gas industry expansion, but not so good for Appalachia or, really, for anybody. U.S. LNG export capacity is primed to ramp up and the largest, most economic natural gas basin is left out of the action, unable to increase production to meet the higher demand. The result will be higher prices both domestically and internationally, adding to the pressure on struggling European economies.

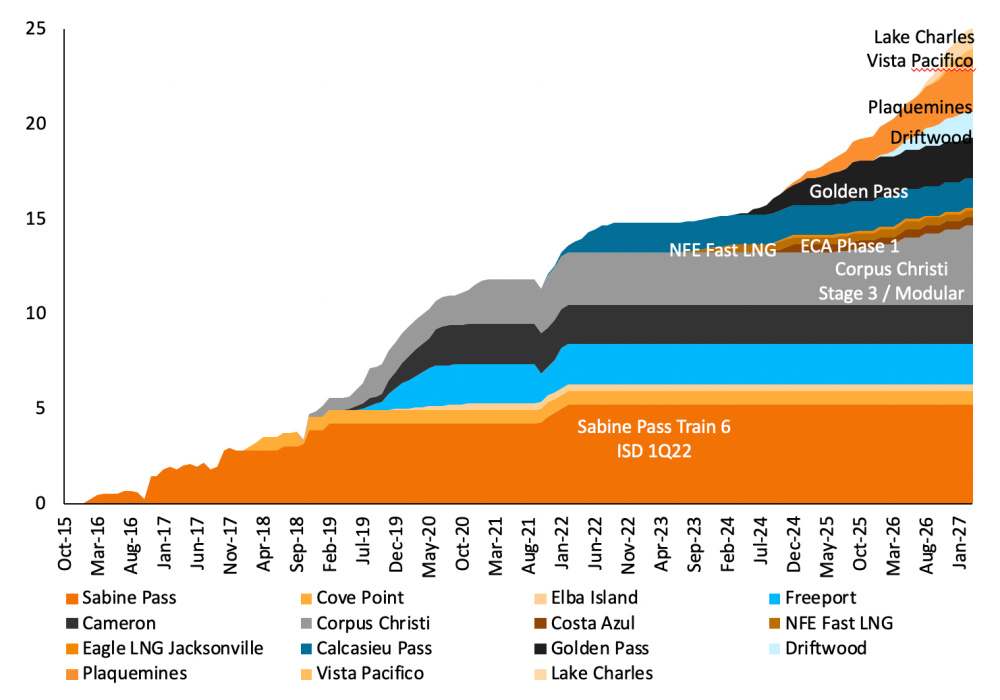

Agreements to supply LNG, already on the rise, accelerated following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February. But the growth in U.S. export capacity really starts when the Golden Pass terminal comes online in 2024, Little said, and peaks in 2026.

The U.S. exports about 11 Bcf/d of gas at the moment, he said, a figure that will jump to 13 Bcf/d when Freeport LNG is able to fully return to service. Maquarie forecasts an expansion to 25 Bcf/d by the end of 2027. U.S. gas production, now around 100 Bcf/d, will creep up to 103 Bcf/d by the end of the year and rise to 110 Bcf/d by the end of 2023, Little said.

Everywhere but east

The problem, he said, is the shift in production growth. The Haynesville is showing strong production growth, as is the Permian Basin from associated gas, an uptick in gas drilling in the Eagle Ford and even a small resurgence in the Barnett. There are expectations of growth in the Midcontinent, too. Just not in the Marcellus and Utica.

“If you have to get an act of Congress to get your permits to build a pipeline... this is not a great environment to build midstream infrastructure.”—Kevin Little, Macquarie Energy

The culprit is the old pipeline constraints bugaboo. More production can’t come online until more takeaway comes online and more takeaway won’t come online because states in the Northeast simply won’t allow it. It wasn’t always this way.

“It really wasn’t that long ago—2018-2019—we built a significant amount of new pipeline capacity coming out of the Northeast,” Little said. “In just three years, we built 12 Bcf/d of new pipeline capacity and several of them were major projects, including the Rover pipeline, Nexus, Atlantic Sunrise and then the Leach Xpress and Gulf XPress.”

At the time, there were fears of an overbuild in the Marcellus and Utica, but the plays proved the markets wrong very quickly. Production grew by more than 9 Bcf/d in 2018-2019, easily backfilling all of the new capacity. And from the gas production boom in the Northeast sprung the first wave of Gulf Coast LNG expansion (debut of Cheniere’s Sabine Pass LNG, construction of Cameron LNG and Freeport LNG facilities).

Then, up north, things went south. Pushback against midstream infrastructure took the form of states like New York and New Jersey used Section 401 of the Clean Water Act to delay or deny certification of projects like the Constitution pipeline and Northeast Supply Enhancement project. CPV Valley Energy’s ultimately successful effort to build an eight-mile lateral pipe took years in court and massive cost overruns.

Even wins at the Supreme Court became Pyrrhic victories when the Atlantic Coast and Penn East pipelines were canceled.

“If you have to get an act of Congress to get your permits to build a pipeline, if you’ve got to go to the Supreme Court and you still can’t build a pipeline, this is not a great environment to build midstream infrastructure,” Little said. “And so, you’ve not seeing a whole lot of new pipelines proposed.”

Even if the 2 Bcf/d Mountain Valley Pipeline manages to find its way through the permitting maze, it won’t be able to change the equation much. The process to gain approval from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) takes four to six years, so major pipeline construction that would result in sustained growth in the Marcellus and Utica won’t happen anytime soon.

Resistance to pipeline construction has made Northeastern states reliant on LNG imports to balance their markets in winter. With global demand rising, the price of those imports could soar as high as $100/MMBtu.

“It’s a very significant impact that will result in significantly higher prices for consumers in New England,” Little said. “In spite of being, geographically, very, very closely located to one of the cheapest gas basins in the world.”

Recommended Reading

NGL Growth Leads Enterprise Product Partners to Strong Fourth Quarter

2024-02-02 - Enterprise Product Partners executives are still waiting to receive final federal approval to go ahead with the company’s Sea Port Terminal Project.

Nebula Energy Buys Majority Stake in AG&P LNG

2024-01-31 - AG&P will now operate as an independent subsidiary of Nebula Energy with key offices in UAE, Singapore, India, Vietnam and Indonesia.

Enbridge Advances Expansion of Permian’s Gray Oak Pipeline

2024-02-13 - In its fourth-quarter earnings call, Enbridge also said the Mainline pipeline system tolling agreement is awaiting regulatory approval from a Canadian regulatory agency.

Sunoco’s $7B Acquisition of NuStar Evades Further FTC Scrutiny

2024-04-09 - The waiting period under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act for Sunoco’s pending acquisition of NuStar Energy has expired, bringing the deal one step closer to completion.

Global Partners Declares Cash Distribution for Series B Preferred Units

2024-04-15 - Global Partners LP announced a quarterly cash dividend on its 9.5% fixed-rate Series B preferred units