The Northeast knows all about gridlock, whether it be the traffic in New York, Philadelphia, Boston—or traffic and legislative blockages in Washington, D.C.—there are no shortages of logjams throughout the region.

Midstream bottlenecks are just the latest in a long series of stoppages.

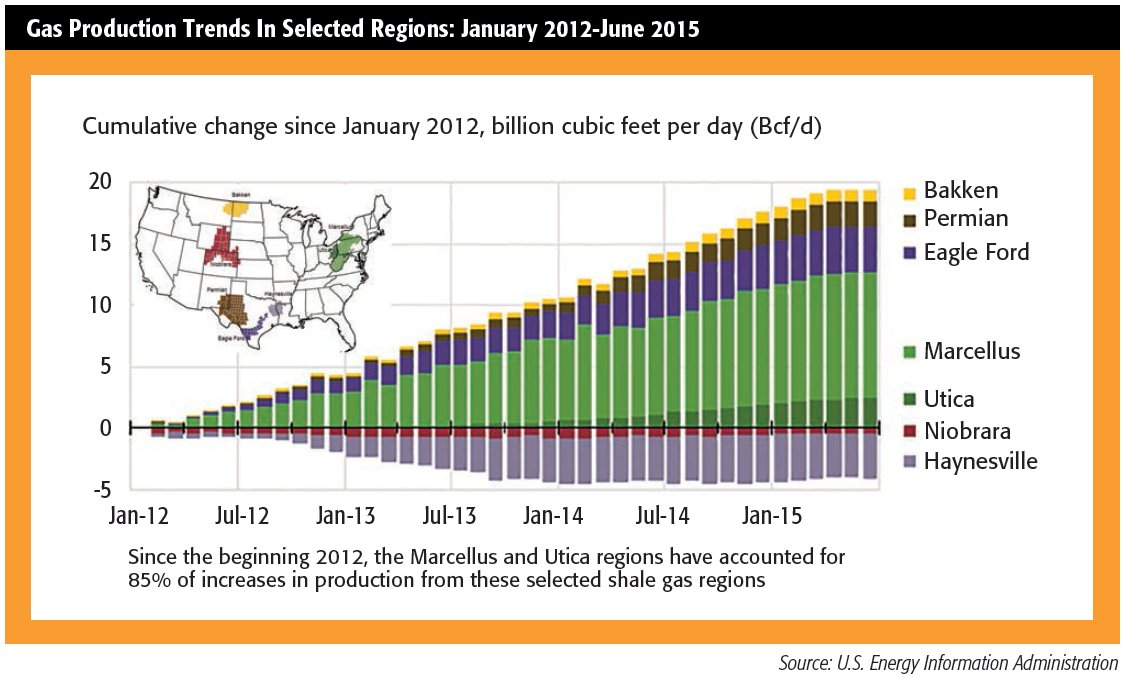

Luckily, there aren’t shortages of projects designed to get production out of the Marcellus and Utica shales and to market–both home and abroad. Shale plays may be old hat for many in the oil and gas industry, but it’s worth remembering how new the industry is for many in the Northeast and how long construction can take in the region.

It’s both an exciting and uncertain time for the industry and no region better exemplifies the changing landscape more than the Northeast. Long a demand center for the hydrocarbon industry, the region is firmly entrenched as a dual supply-demand center, thanks to the sheer size of the Appalachian Basin’s Marcellus and Utica shales and their proximity to large population centers.

“The Marcellus is such a valuable, abundant asset for our region and our country. In fact, it is such a prolific asset that the supply available to the region significantly outstrips regional market demand. Therefore the excess supply needs to find markets out of the region,” Don Raikes, senior vice president–customer service and business development at Dominion Energy, told Midstream Business.

Volumes won’t be moving in any one direction; rather, they will move to multiple markets.

A compass strategy

“As we reviewed this oversupply dynamic, we developed our compass strategy to move gas out of the region. We have projects that move gas north, south, east and west,” he continued.

While there won’t be any one, single market for Marcellus and Utica production to move, the Gulf Coast will receive a sizable portion of volumes out of Appalachia.

“There are a lot of projects currently proposed to move Marcellus and Utica production all over the place. We’ve seen a few pipelines that have started to move gas to the Midwest from Pennsylvania. A lot of it is moving to the Gulf Coast due to the power generation demand and the amount of petrochemical and export capacity in the region,” Rob Desai, analyst, equity research, at Edward Jones, told Midstream Business. He added that a challenge is that both credit and equity markets are making it harder for midstream companies to raise capital for new projects.

There is also potential for shipments to Canada and the Southeast, though both areas are regions where shipments could take time to really develop. Canadian companies are developing pipeline projects to move domestic gas to the East Coast, which would force Marcellus gas into a competition with these Canadian volumes.

This multimarket approach is quite the change from just a few years ago when it was assumed production would primarily move east, but it is still having a positive impact on the region. Raikes noted that the Marcellus Shale is a global phenomenon known around the world. However, the global market is tight, and there isn’t as much room for growth as there is for displacement of gas and liquids from other sources, which is causing producers and operators to widen the search for ways to relieve this bottleneck.

Keeping it local

When the Marcellus Shale first made headlines, the assumption was that the Northeast’s large cities like New York City and Philadelphia would be the primary beneficiaries of production on an end-use basis. As the size of the play’s recoverable volumes increased, so did the scope of the potential markets to areas outside of the region such as the Gulf Coast, New England and the Southeast—little attention was paid to local markets. However, there are strong opportunities for this production at home in central Pennsylvania.

“Pennsylvania is in a great position to increase the availability of natural gas and keep prices competitive with other parts of the country,” Anthony Cox, director, midstream business development at UGI Energy Services, told Midstream Business.

The company traces its roots in the state to 1882 through its parent UGI Corp. Though the two companies don’t operate as closely as other parent-subsidiaries because regulations place constraints over utility-midstream operator parent-subsidiary relationships, the experience in the state still forms a critical part of UGI Energy Services’ operations.

“We have a fairly specific geographic focus where we operate in the areas that we are experienced in. UGI has been here a long time. Pennsylvania has a complicated regulatory structure with a lot of nuances and, despite now more than a decade of experiencing shale gas, natural gas delivery is still new to many communities. So, having company roots that go back more than 130 years helps build and ensure local trust where we’re operating,” Cox said.

The biggest opportunities for UGI Energy Services are in bridging the gaps that exist between producing regions in the western and northern parts of the state with the high-demand regions in south central and southeastern Pennsylvania, while also delivering volumes to neighboring states.

Two recent projects with this goal in mind are the PennEast and Sunbury pipelines. PennEast is designed to bring Marcellus gas into the New Jersey market as well as into Manhattan through shipping agreements with Con Edison.

The $1 billion PennEast Pipeline will run 118 miles from Dallas, Pa., to Pennington, N.J., where it will ultimately interconnect with the Transco Pipeline. “There’s a lot of gas being moved in the area where PennEast starts, and it will hit some critical delivery points in Pennsylvania very close to power generation as it moves south to New Jersey,” Cox said.

The 35-mile Sunbury Pipeline will run from Lycoming County, Pa., to Snyder County, Pa., where 180,000 dekatherms (Dth) per day of its initial capacity of 200,000 Dth per day will be contracted to the Hummel natural gas-fired power plant.

Rising costs

The number of projects being developed in the region is partially responsible for increasing the cost for labor and materials and making project development more complex. According to Cox, the cost of pipe has risen from $2 million per mile to $7 million to $10 million per mile. “It never gets cheaper, it only gets more complicated and expensive,” he said.

Additionally, the terrain and the regulatory environment in the Appalachian Basin make it more difficult to build in compared to places like Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana. Those areas have flatter land and sandier soil as well as a more streamlined regulatory structure.

UGI’s experience in the region helps provide the company and its affiliates with a competitive advantage, especially in understanding the local geography. There is still risk involved with the development of new infrastructure, which requires trust in the future growth of the natural gas market.

“We’re here for the long haul because we’ve been here a long time. A lot of the existing distribution system that UGI Utilities operates in northern Pennsylvania was originally built as gathering infrastructure from conventional wells that were depleted many years ago. There’s a long history of playing a role in that energy development,” Cox said.

Powering the future

While Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia may have different terrain than Texas and Oklahoma, the oil and gas industry in in the Appalachian Basin is similar to those regions as it is a multigenerational industry. Construction and drilling in the region will be taking place for decades as the Marcellus and Utica extend their reach into other parts of the country.

Cox said that projects like PennEast and Sunbury are needed to move supplies and bridge the market gap, but there is also a need for creative programs to build out the distribution system. He cited UGI’s Growth Extension Tariff (GET) program, which allows new customers to extend the cost of extending utility lines to their properties over a 10-year period.

“These innovative programs allow utilities to make assumptions of future growth potential and spread out the full cost of the expansion into an area where customers aren’t necessarily signing up on day one. These programs are really needed in Pennsylvania to increase the use of natural gas,” Cox said.

One of the reasons for these types of programs is to combat the biggest challenge in the region, which is inertia. Thus far the most success in developing a new market for natural gas in Pennsylvania, and most other parts of the country, has been through power generation.

Gas conversions

On the surface it may seem as though the coal-to-gas power generation conversions taking place are due to the lower cost of natural gas vs. coal, but that is not typically the case.

“It’s not so much pure market-driven economics. A lot of these conversions have been driven by regulatory requirements driving coal-fired plants to shut down,” Cox said.

However, natural gas is making headway on a market basis in converting home heating and industrial customers from heating oil due to the considerably lower costs associated with gas. Compared to heating oil or propane, natural gas is also more convenient for customers, as it is piped into the home rather than needing home delivery.

The real headwind for converting customers has been the significant upfront costs associated with the conversion. “These conversions are economically viable and tend to have relatively short paybacks, but they require upfront capital investments and the confidence that the pricing advantage will be there on a long-term basis. The delta may have closed recently, but gas still represents a significant savings over oil,” Cox said.

Pennsylvania has sponsored several programs to help its citizens convert their heating systems to natural gas, but Cox said that more can be done by the state to help continue the industry’s growth. Most notable would be an attractive tax program for businesses to help them make the necessary large investments in the region.

“Pennsylvania needs to be more business friendly. The state should leverage its position as the country’s second-largest natural gas producer to attract new businesses, not scare them away with new energy taxes,” Cox said. “We have the second-highest corporate net income tax rate in the country.”

He added that there is also more work to be done when it comes to the regulatory environment. “There are a lot of environmental restrictions and multiple agencies that all do the same thing, which requires companies to go through two to three different agencies. There is a lot of efficiency that can be gained by streamlining this to one agency. Pennsylvania is definitely not the worst place in the country to work, but it could be friendlier for this industry,” Cox said.

Avoiding a calamity

Though UGI Energy Services is focused on local markets, Cox cited the need for increased transmission capacity, specifically to New York and New England, to open up new markets for Pennsylvania production.

“On the coldest day of the year, people pay more for energy in those regions than anywhere in the world and that’s simply a matter of a bottleneck in the transmission infrastructure on a relatively short haul. It’s easy to cross on a physical basis, but there are a lot of regulatory hurdles to overcome in order to build pipe,” Cox said.

He added that this constraint could become worse as more natural gas-fired power generation comes online in the next three years.

“It’s a little scary to think of this new power generation coming online without new infrastructure. It could be calamitous with the same limited transmission capacity and even more demand. We need to build this infrastructure now and not wait until we have a real crisis,” Cox said.

Interruptible service problems

The current transmission systems for Marcellus gas to these markets may work fine on non-peak days, but Cox said it is a less than perfect system on peak days because it forces interruptible customers to either use alternate fuels or, if they continue to use natural gas, do so by accessing a very tight spot market, invariably bidding up the price of natural gas. “To me, that is not working perfectly; in a perfect world, everyone that wants to use natural gas should be able to do so and unfortunately every winter that’s not true,” Cox said.

He added that interrupted service also drives up fuel costs for consumers and can result in unplanned outages as a result of low pressure points within the distribution system or plants having to shut down because they can’t find an alternate fuel source.

This situation is much stronger in Pennsylvania than in other parts of the country as 80% of new capacity in power generation has been natural gas fired. PJM, the regional transmission organization that, in part, serves Pennsylvania, will be adding more than 6,000 megawatts of combined cycle gas plants in the next three years.

Market impact

Cox acknowledged that the current commodity price downturn was having an impact on the region, especially for producers, but believes that the situation places more impetus on building new pipelines in order to enhance the region’s takeaway capacity.

An obvious sign of the impact of the downturn on Marcellus producers has been the production turnover in the region, which began in the spring of 2015 after peaking in April. Ultimately, this will be a positive, though, as it will allow supply and demand to come more into balance.

Desai said that he anticipates crude oil prices to remain volatile for the next several years as supply continues to outpace demand. It’s difficult to forecast the impact this volatility will have on NGL prices since their relationship is changing.

“Historically, liquids prices have been based off of oil, but that’s no longer the case and liquids are trading even lower than in the past. We think that will continue going forward because of the supply outlook,” Desai said.

The road south

It will take until the end of this decade for the Southeast market to begin to further grow. While it is switching to natural gas-fired power generation, the bulk of this capacity is contracted by Gulf Coast producers.

While pipeline capacity into the West and South is being built, both markets are already fully supplied and the production into those regions isn’t going away anytime soon.

“Marcellus gas moving to the South could extend the geographic area of depressed gas prices because the existing producers from Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana won’t give up their gas markets,” Dan Lippe, managing partner, Petral Consulting Co., told Midstream Business. This production has the advantage of flowing through older pipeline systems at lower tariffs compared to gas from the Appalachian Basin.

Dominion’s 564-mile Atlantic Coast Pipeline has allowed Marcellus supplies to make inroads into the Southeast market. Atlantic Coast, which is 96% contracted for its 1.5 billion cubic feet per day, passes through West Virginia, Virginia and North Carolina.

One of the unique aspects of this pipeline is that it was developed as a result of a request for proposal from end users rather than from producers. It is these end users, including Duke Energy, Dominion Virginia Power, Piedmont Natural Gas, Public Service of North Carolina and Virginia Natural Gas that have contracted the system’s capacity.

Market-driven pipeline

“What separates this project is that this is a market-driven project, as opposed to a producer-push project. The primary use for the supplies will be for power generation to meet growing market and environmental targets. The strategic location of this project also provides for future growth to these dynamic markets,” Raikes said.

The markets that the Atlantic Coast Pipeline will serve remain one of the largest demand growth centers in the U.S. On a long-term basis, the U.S. Census Bureau predicts a population increase of 2.1 million in North Carolina and 1.8 million in Virginia by 2025.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration reported that in the six-year period from 2008 to 2013, natural gas-fired power generation demand greatly increased in both states with North Carolina increasing by 459% and Virginia by 123%.

When you think of the Marcellus and Utica, one midstream player that is relatively quiet in the play is Enterprise Products Partners LP, but the company plays a very important role in the region nonetheless through its 1,230-mile Appalachia to Texas (ATEX) Pipeline.

This system went into service in 2014 and has been helping to solve the Appalachian Basin’s ethane “problem” by providing transportation capacity for up to 190,000 barrels per day (bbl/d) of ethane out of the Marcellus and Utica from Washington County, Pa., to Mont Belvieu, Texas.

The benefit of moving this production to the Gulf Coast is because of the unsurpassed fractionation and cracking capacity at the Mont Belvieu, Texas, complex as well as the increasing export capacity offered from the Gulf Coast.

“We focus as much on the demand side of the equation as we do on the supply side,” Bill Ordemann, executive vice president–commercial, Enterprise Products Partners, said at Hart Energy’s Midstream Texas conference last October.

Ethane exports

Indeed, Enterprise is developing an ethane export terminal from the Houston Ship Channel, following the success of its LPG export terminal in the region.

“Energy exports are critical to the U.S. energy industry today. Without LPG exports where would we be? We’re already dependent on exports to keep our industry healthy. We have contracts for exports to northwest Europe and Asia. It’s plentiful, reliable, cheap and sustainable,” Ordemann said. He added that the increase in demand for ethane and ethane exports will help out the natural gas markets.

The Marcellus may be bigger than every other gas play, but its later development means that its supplies are coming online at a time when many other plays have locked up various domestic markets through long-term contracts.

“I don’t think there is any market for natural gas beyond the borders of the Marcellus until pipeline capacity into the East and Canada is built,” Lippe said.

The news isn’t much brighter when it comes to coal-to-gas conversions, as Lippe stated that coal companies will fight government mandates to shut down coal-fired power plants and could tie up these conversions for years or even decades in the courts.

There are already a great deal of coal-to-gas plant conversions that have taken place or are set to take place in the U.S., which are already factored into growth forecasts.

“The No. 1 underlying fundamental is zero growth in demand for electric power in the U.S. It has been true for 10 years and will continue to be true because of federal mandates requiring continuous improvements in efficiency of everything that uses electric power,” Lippe said.

Should Marcellus gas struggle to gain domestic market share, it is possible producers will be forced to shut-in production for six to eight months per year.

“It’s still a seasonal business. Producers cannot produce all of the gas that they have the capability of producing. The market is not there yet, and I don’t see that changing in the next five years,” Lippe said.

Finding foreign markets

It is not all bad news for Marcellus gas as it is set to make moves in the LNG export market though Cheniere Energy Inc.’s Sabine Pass, La., terminal and Dominion Resources Inc.’s Cove Point terminal in Lusby, Md.

Cove Point, like Sabine Pass, is a former import terminal that is being re-purposed to export LNG from the U.S. to foreign markets. While Sabine Pass receives a portion of its volumes from the Marcellus, Cove Point is focused entirely on exporting Marcellus gas.

Cove Point’s two main customers are in India and Japan, which on the surface may be unusual due to the longer travel time. However, both countries are growing markets for LNG and require secure volumes for the long term.

“Travel times to the Asian markets will be about one month, but the global LNG supply is projected to become more liquid and cargos more fungible as more liquefaction plants come online through 2020. This will likely lead to cargo swapping to drive out transportation inefficiencies. Cove Point is also ideally situated to deliver cargos to Europe, which has historically been a balancing market,” Raikes said.

Cove Point secured the first U.S. liquefaction deal with a Japanese company by securing a contract with Sumitomo Corp. and Kansai Electric. Japan imports almost all of its energy to fuel their economy, and it was important for them to have U.S. supplies as part of their energy portfolio. “One of our colleagues from Japan compared the significant natural gas reserves in the Marcellus and Utica to the historic oil reserves held by Saudi Arabia. He called the United States Saudi America,” Raikes said.

India’s LNG need

The other half of Cove Point’s capacity is held by the U.S. affiliate of GAIL (India) Ltd. Raikes said that ample and competitively priced energy supplies are necessary to support India’s population and economic growth as the country’s population is expected to exceed China’s in the next 10 years.

“India’s need for LNG remains strong and their imports continue to increase. U.S.-sourced LNG will remain a low-cost option to typical oil-linked contracts,” Raikes said.

LNG is also being used for domestic peak shaving at UGI Energy Services’ Temple, Pa., facility just north of Reading. “It’s a unique site because it can do a lot of things. It not only liquefies, but it also has 1.25 billion cubic feet equivalent of LNG storage and the ability to terminal and truck it away as well as vaporize it into the local distribution system and the Texas Eastern transmission system for peak shaving,” Cox said.

UGI Energy Services is also developing the $60 million Manning LNG plant in Wyoming County, Pa., adjacent to the company’s Auburn gathering system. The facility will include both liquefaction and storage with a capacity of 120,000 gallons of LNG per day when it comes online in early 2017. “This will be right in the middle of Wyoming County to take advantage of the low cost gas being put into the Auburn system in Wyoming and Susquehanna counties,” Cox said.

Locating key components

Similarly, NGL will have much easier access to both domestic and foreign markets than dry natural gas because they can be exported in large quantities and stored easier than dry gas. According to Lippe, besides local markets and the Northeast, where Marcellus and Utica production moves, is a function of where there is storage capacity to accept the surplus that exists during the offseason.

“The volumes are significant–we’re talking 150,000 bbl/d of product at the summer peak that needs to be shipped from the Appalachian Basin to someplace with storage capacity. The only place in North America with spare storage capacity is Mont Belvieu. All of that surplus has to move there with a lot of it being sold offshore as LPG or ethane exports,” Lippe said.

The advantage that NGL has over natural gas is that the petrochemical industry is building new facilities to use ethane and propane in both the U.S. and China. This renaissance of the petrochemical industry is the largest new market in the near- and short-term for the Marcellus and Utica shales, but it is not a growth market.

Instead, Marcellus and Utica production will have to displace other production being used as feedstock for the North American petrochemical industry. This is a sizable market because the U.S. currently consumes between 25 billion pounds and 30 billion pounds per year of polyethylene. One-third of this production, or 10 to 12 billion pounds per year, is purchased by plastics fabricators in the Northeast.

Cracker capacity

In the U.S., this new capacity is being built along the Gulf Coast, but there are several high-profile projects being discussed in the Northeast. The most notable is Shell Chemicals’ proposed multibillion dollar world-scale ethane cracker that would be built in Beaver County, Pa.

The facility has been moving along as the company has secured several environmental permits, but no formal decision has been made on the project. All signs point to the project moving forward, according to Lippe.

“Shell is going to build a plant. They have three of their environmental permits and bought their property. It may take another three to four years, but they appear to be moving forward. They will look to sell as much of their production to local plastics fabricators since that market is big enough for Shell to sell out to the market,” Lippe said.

There are also a few smaller, but still expensive, projects that have been announced by other companies, including Braskem and Odebrecht’s Project ASCENT cracker in Parkerburg, W.Va.; Appalachian Resins’ 600 million pounds per year cracker in Monroe County, Ohio; and PTT Global Chemical’s cracker in Belmont County, Ohio. The Braskem/Odebrecht project has been postponed, but not cancelled, while the other two projects are also being reviewed.

Ontario, Canada is viewed as an extension of the Marcellus-Utica market by more in the industry because of the relative close proximity and sizable hub. “Ontario is part of the overall Marcellus market, it just happens to be under the control of the Canadian government,” Lippe said.

One of the key players in Sarnia, Ontario, is Nova Chemicals Corp., which is expected to further expand to take advantage of production out of the Marcellus and Utica. “Nova Chemical has a big advantage over companies looking to build petrochemical facilities in Pennsylvania, West Virginia or Ohio, which is they have storage capacity,” Lippe said.

He added that the biggest headwind for the development of a true Northeast hub is the lack of storage in the region. “The fundamental problem and reason pipelines to the Gulf Coast are needed is because there isn’t any storage. The area needs 20 million to 30 million barrels of storage,” Lippe said.

This lack of storage will make it difficult for the region to house multiple crackers. A single cracker in the region could coordinate its maintenance and downtime while notifying shippers that they will need to go into ethane rejection. More than one cracker makes it more difficult for this coordination and the lack of storage will make this very difficult.

Smaller, more flexible hub

There is an old saying that to be successful, you don’t have to make the most money, you just have to make a lot of it. On a similar note, the Northeast doesn’t need to—nor can it—recreate a hub the size of the Mont Belvieu gas liquids hub to be successful. The region only needs to build a hub that can help open more markets—both domestically and internationally.

In this case, Sunoco Logistics Partners LP’s Marcus Hook Industrial Complex outside of Philadelphia will serve this function. This facility includes an LPG, refined products and crude oil terminal with 2 million bbl of underground NGL storage capacity.

Besides the facility’s location, which is more than 300 miles away from the heart of the Marcellus, its flexibility is its biggest benefit. Marcus Hook is capable of receiving NGL volumes via pipeline, truck, rail and marine transport and can send out volumes via pipeline, truck and marine transport.

Sunoco Logistics can export LPG and ethane out of its Mariner East system, which provides Marcellus and Utica producers with access to foreign markets. During a conference call to discuss third-quarter earnings, President and CEO Michael Hennigan highlighted Sunoco’s ability to further scale its Mariner East operations.

“We remain bullish on the liquids potential in the Marcellus-Utica region. Our Mariner East 2 project, announced with a design target of 275,000 bbl/d, continues to press through the engineering and permitting phases, as we target an end of 2016 start-up date. … Mariner East 2 service can be scaled to a higher capacity, with relatively low additional capital, as more demand is created with the full upside capacity of 450,000 bbl/d. Once fully online, Mariner East 2 together with the 50,000 bbl/d at Mariner West and the 70,000 bbl/d at Mariner East 1, will be capable of providing approximately 600,000 bbl/d of NGL pipeline takeaway capacity from the Marcellus and Utica shales,” Hennigan said.

Mariner East expansion

Sunoco Logistics is also considering further expansion of the Mariner East system to 800,000 bbl/d of shipping capability to local and international markets. “The Mariner East system has a decided logistics advantage over the Gulf Coast for both the local and international markets. Locally, there is a seasonal premium in the Northeast market, which can be accessed from our pipe terminal and truck rack systems. From a waterborne perspective, this is about 1,500 miles closer to Europe, with no nighttime restrictions, and no ship congestion as seen in the Houston Ship Channel,” Hennigan said.

According to Hennigan, the Northeast propane demand in winter doesn’t get enough attention when compared to shipping volumes to the Gulf Coast.

“We believe that no Marcellus-Utica NGL should go to the Gulf Coast, because we don’t think that’s the right opportunity for the best net-back. … We’re obviously advantaged to the European market, but we also say we’re at par with the other markets. … We’re at par with the Gulf Coast as far as shipping into the Panama Canal. It continues to be our goal to convince people that projects to the Gulf Coast don’t make sense.”

There may be disagreements among producers, midstream operators and analysts on the best markets for Marcellus-Utica production, but one thing everyone can agree on is that there are still bottlenecks in place—but they are set to be cleared in the coming years. That will allow the Marcellus and Utica to achieve their world-class potential.

Recommended Reading

US Drillers Add Oil, Gas Rigs for First Time in Five Weeks

2024-04-19 - The oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, rose by two to 619 in the week to April 19.

Strike Energy Updates 3D Seismic Acquisition in Perth Basin

2024-04-19 - Strike Energy completed its 3D seismic acquisition of Ocean Hill on schedule and under budget, the company said.

FERC Again Approves TC Energy Pipeline Expansion in Northwest US

2024-04-19 - The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission shot down opposition by environmental groups and states to stay TC Energy’s $75 million project.

Eversource to Sell Sunrise Wind Stake to Ørsted

2024-04-19 - Eversource Energy said it will provide service to Ørsted and remain contracted to lead the onshore construction of Sunrise following the closing of the transaction.

Shipping Industry Urges UN to Protect Vessels After Iran Seizure

2024-04-19 - Merchant ships and seafarers are increasingly in peril at sea as attacks escalate in the Middle East.